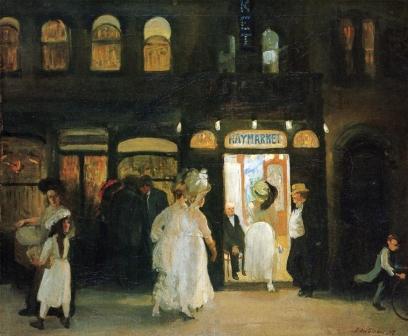

John Sloan’s depiction of the Haymarket 1907

To get you in the mood for the weekend, every other Friday we’ll be celebrating ‘FRIDAY NIGHT FEVER’, featuring an old New York nightlife haunt, from the dance halls of 19th Century Bowery, to the massive warehouse spaces of the mid-90s. Past entries can be found HERE, including articles on New York’s oldest continuously operating bar, the nightclub that caused a Clash riot, and the bar that threw out Humphrey Bogart.

I’ll be bringing this feature back once in a while, because there are dozens more nightclubs, saloons and speakeasies of the past just waiting to be explored. And what a better choice to restart than the dance hall known as the Moulin Rouge of New York, a lively, brightly lit cabaret with debauchery for everyone — the Haymarket.

The Tenderloin district of Manhattan hosted the city’s biggest assortment of vice industries in the late 19th/early 20th century. Sure, Five Points gets all the press, but this vast area — approximately everything between 23rd and 42nd streets, and 6th and 9th avenues — was the more likely destination for regular New Yorkers who wanted to dally in illicit entertainment. It was at the edge of more fashionable districts (Broadway to its east, Ladies Mile south) and many of its more successful ventures drew respectable gentlemen looking for respite from Gilded Age propriety.

Haymarket was the Tenderloin jewel, a three-story dance hall illuminated (disguised?) like a legitimate Broadway theatre and named for an even more legitimate British theater district. New York’s chief of police in 1887 described it as “animate with the licentious life of the avenue.”

Briefly, it really was a theater, called the Argyle, originally opening in 1872, before its owner got wise and reopened in 1878 as a saucier and more profitable dance hall. Its location, on 66 West 30th Street at Sixth Avenue, placed it just a few blocks from legitimate society, but its bevy of scintillating options were miles outside New York’s traditional morals.

With bands playing and high kicking saloon girls swirling about the floor, owner Edward Corey maintained his club was legally ‘above board’. In a quote from Timothy Gilfoyle’s ‘A Pickpocket’s Tale’, “An innocent man and his wife could have wandered into the Haymarket and been entirely unconscious of what was going on around them.”

In fact, those girls were most often prostitutes. Nicknamed ‘the prostitutes’ market’, the Haymarket was a veritable sin shopping mall, ladies luring men to tables to buy them champagne, shower them with presents and quite often making their way to curtained rooms in the balcony and upper floors. If you preferred male prostitutes, you simply made your way to the back entrance. And although girls and boys were strictly forbidden by management to rob their clientele, the Haymarket nonetheless became a paradise for thievery.

Below: the crowded late night streets of the Tenderloin (picture courtesy Ephemeral NY)

Even still, its reputation grew as New York’s liveliest party in the 1890s, a flashy, fleshy dive thumbing its nose at society. Women drank for free and were allowed to carouse and drink freely with men, who paid a one-quarter entrance fee for the privilege of joining them. Respectable gentlemen joined riff-raff from local opium dens on the dance floor, their arms around painted, corseted ladies. Naturally, the Haymarket thrived with the help of police corruption and bribery: $250 a week greased the palms of law enforcement who looked the other way. When it actually was closed during rare moments of police reform, it simply re-opened under different names.

Its abandon inspired writers like Stephen Crane and even Eugene O’Neill, who wrote of the club:

The music blares into a rag-time tune —

The dancers while around the polished floor;

Each powdered face a set expression wore

Of dull satiety, and wan smiles swoon

John Sloan painted the Haymarket in 1907, still lively in his depiction though in its waning days by the time he put paint to canvas. (The painting currently hangs at the Brooklyn Museum). The hall even became the subject of a 1903 silent film A Night At The Tenderloin.

The Haymarket finally shut down for good in 1911, just as the neighborhood was itself transforming, with the construction of Penn Station and the development of Times Square clearing away much of the Tenderloin’s vice. Standing at Sixth Avenue and 30th Street today, you’d have no idea that one of New York City’s biggest parties once raged here.

4 replies on “Friday Night Fever: Haymarket, New York’s Moulin Rouge”

NYC…. Paradise Northeast… if we get through all this…please put us on the invitation list!

[…] much of their free time wandering downtown Manhattan and frequenting pubs like McSorley’s and the Haymarket. Paintings from this time depict the variety of life unfolding around them. Luks’s Hester Street […]

[…] lot of their free time wandering downtown Manhattan and frequenting pubs like McSorley’s and the Haymarket. Work from this time depict the number of life unfolding round them. Luks’s Hester Road (1905) […]

[…] much of their free time wandering downtown Manhattan and frequenting pubs like McSorley’s and the Haymarket. Paintings from this time depict the variety of life unfolding around them. Luks’s Hester Street […]