A tantalizing stretch of New York nightlife history lies in the shadows, illegally operated, often fueled by police bribes — the opium dens of Chinatown and the speakeasies of the Village and midtown.

There were also hundreds of illicit gambling rackets, called ‘poolrooms’, throughout the city in the late 19th century, usually alongside the seediest of taverns, brothels and poolrooms.

Naturally, the pastime was not looked upon lightly by proper society. “The poolroom keeper, like the proverbial worm,” remarked one New York Times article from 1900.

But New York’s wealthy elite liked to gamble as well, and there was no need for them to step into such filthy, disreputable places. The rich had their own houses of vice.

And one, the House with the Bronze Door, which opened in 1891, would have rivaled the great casinos of the day in terms of its lush presentation.

House of Cards

The fine townhouse at 33 West Thirty-third Street sat right around the corner from the Waldorf-Astoria, so close to respectable Fifth Avenue that people certainly strolled by it with no clue of the entertainments within.

Its glorious, defining feature — and where it gets its name — was a $20,000 Italianate Renaissance, 15th century bronze door which gave the building the feel of a classic structure, or perhaps a bank vault.

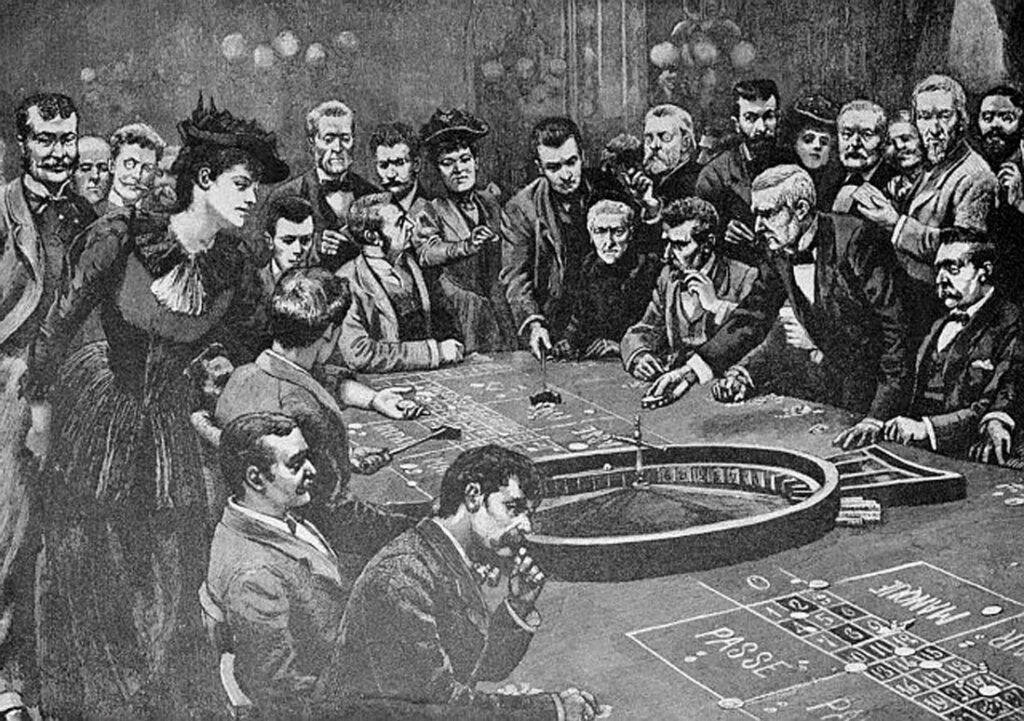

Luxury greeted those who were fortunate to peer behind that door, imported old school finery, from vases to oil paintings on rich wallpapered walls, along hallways in red velvet carpeting, leading to game rooms with European oak tables hosting games of roulette, poker and baccarat.

In a place where wealth exchanged hands nightly, it was reflected in the imported banisters and marble bathrooms.

High Stakes

And it wasn’t just how it looked, but who designed it to look that way — none other than Stanford White of the city’s most prestigious design firm McKim, Mead and White, a gambling man himself who hired a team of Venician craftsman to give the gambling house its distinctive glamour.

The building next door also belonged to the casino, but was less impressively designed; its sole purpose was as an exit in case of police raids.

The owner Frank Farrell* was New York’s gambling kingpin, using profits from the Bronze Door to fund over 200 illegal gambling houses throughout the city and grease the palms of police officers to ensure they all stayed open.

If that name sounds familiar to sports fans, it’s because of a riskier gamble Farrell made in 1903 with his business partner William Stephen Devery. (Yes, the former police chief. See how it used to work back then?)

The two purchased the Baltimore Orioles, moved them to New York, lost a lot of money, renamed the team as the New York Yankees and promptly sold them to beer mogul Jacob Ruppert.

Below: Farrell with a Yankees team member in 1912. He would sell off the losing team a few years later. Courtesy Library of Congress

A Night at the Tables

The only people taking risks at the Bronze Door, however, were the rich and well connected clientele. On any given evening you could find the head honchos of Tammany Hall smoking cigars in the corner, or ‘Diamond’ Jim Brady and his entourage at the upstairs roulette wheel.

According to Lloyd Morris: “The casino was conducted with the quiet decorum of a gentleman’s club.” These men expected the royal treatment, and they got it. A midnight buffet of lobsters and steaks, open bar of the best liqueurs, fine cigars for a $1 apiece. More importantly, Farrell strictly applied a philosophy of ‘the customer is always right’. Unlike many of Farrell’s downtown dive, where the house often rigged games and marked cards, the gambling den behind the Bronze Door was straight.

There was little nickel and diming here. It’s purported that fifty thousand dollars would hit the tables each night.

Gamblers would win, and then lose, vast fortunes each night. As Luc Sante so elegantly states: “… the stories of rich men dropping enormous sums in a single evening kept topping each other, so that the phenomenon almost comes to seem like a version of potlatch, in which wealth is proven by the ability to shed it.”

Luck Runs Out

The casino stood in defiance of the law for almost a dozen years thanks to Farrell’s connections and the reputation of its clientele. However, given the New York’s waxing and waning reform movements, its time would eventually come, and it did so at the hands of one William Travers Jerome, New York’s district attorney with a particular bent for reform.

Jerome shut down casinos and poolrooms throughout the city and didn’t discriminate, successfully breaching that imposing door and raiding the club in 1908.

Although the games were gone, the place remained open for many years afterwards, as a restaurant owned by the Waldorfs according to official sources. What its true nature was in these later years is unknown.

The building is completely gone today, replaced with a condo and the shadow of the Empire State Building.

Below: District Attorney Jerome, 1915

*Farrell had other partners in the casino, including racetrack owner Gottfried Walbaum and Billy Burbridge, who later became a hotelier in Havana, Cuba.

6 replies on “What’s behind the Bronze Door? Gambling in the Gilded Age”

Law enforcement teaming with gambling, teaming with professional sports. What a concept! Fascinating time in New York City history. Wouldn’t you have loved to be behind that Bronze door. Prohibition certainly promoted the pool room “dives” but it was interesting to see that there was some “legitamate” establishments. The Progressive Movement finally caught up with the illegal activity and curtailed some of the organized crime. Great article.

The former Orioles were brought to New York as the New York Americans, since all American League teams at that time were officially known as ‘Americans’. The newspapers nicknamed the team the New York Highlanders because they played in a park high up on a hill near the Polo Grounds. They were still known as the Highlanders in 1912, the date of the photo, so Farell could not be seen with a ‘Yankee’ since that name didn’t get coined until a year later, when the team moved into the new Polo Grounds and abandoned their hilltop home. The Yankee name was eventually officially adopted by the owners before they sold the Yankees to Jakob Ruppertt in 1915.

My grandfather Cosmo DeSalvo was a friend of Diamond Jim. He gave him a roulette wheel from his casino and my grandfather painted a beautiful painting on it.

Would women have been allowed in the Bronze Door? Or would it have been men only?

I have a large original oil painting that supposedly hung in “the house with the bronze door”. I acquired the painting years ago from an old man that’s father worked at the establishment until its closing. When the Bronze door closed and he lost his job he ended up with the painting. Because his wife considered the painting inappropriate it had been rolled up and stored in an old chest in his attic until his death. do you know of any photographs from inside the Bronze door that I could possibly verify? the painting is large and magnificent and could only hang in an establishment of this sort. This paintings is very unique and definitely has an Irish influence!

Where was the Boardwalk Casino in New York City in the late 1890s and into the first decade of 1900 to 1910 What type of information was provided? Any information would be appreciated.

Thank you