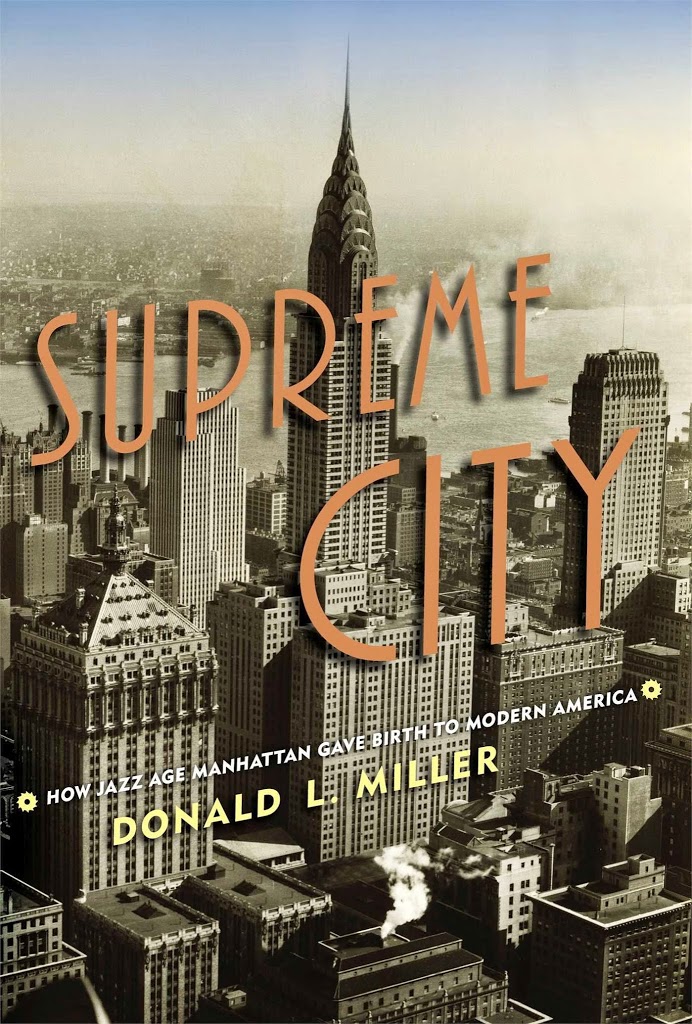

A view of Midtown Manhattan, looking southeast, by the Wurts Brothers (NYPL)

Supreme City

How Jazz Age Manhattan Gave Birth to Modern America

by Donald L. Miller

Simon & Schuster

Supreme City, by Donald L. Miller, certainly one of the most entertaining books on New York City history I’ve read in the past couple years, is also one of the strangest. Almost as an obligation, New York’s Prohibition-fueled nightlife and the rowdy administration of Jimmy Walker are conjured up front, and colorfully so, only to then be placed aside.

This is not a book about the standard subjects of the 1920s. This is indeed an epic about New York City in the Jazz Age, but it’s a wildly different tune than the one in which you’re familiar.

This is a tale of architecture and invention, of a boldness and proportion that New Yorkers take for granted today. Supreme City recounts the invention of Midtown Manhattan, but it’s also about a spiritual shift in urban life. This is the story of how New York City became not only a supreme city, but a supersized one.

Miller, a professor of history at Lafayette College perhaps better known for his works on World War II, approaches the sprawl of New York’s most ambitious decade almost like a mathematician. He ties this epic — a swirl of large personalities and impossible ideas — into a specific intersection of time and place.

It’s as though a slew of particles (comprised of ambitions and personalities) just slammed into each other one day, creating a new form of urban environment.

Industrial visions and personal journeys alike culminate in the year 1927, a watershed date for New York history, and arrive within the Manhattan grid system, mostly along 42nd Street between Eighth Avenue and Lexington Avenue, the nucleus of a new urban vision. The story ventures out through the entire city of course but always to the beat of this new Midtown.

From here, Miller brings in the components of growth, the great innovators and personalities, plotted in relation to each other and to the great city blossoming under their feet.

These aren’t just the standard innovators, the expected cast — David Sarnoff, Duke Ellington, Charles Lindburgh. Sure, you get a bit Texas Guinan‘s drunken swagger, a little of Jack Dempsey‘s scrappiness. But Miller gives equal prominence to perhaps less colorful real estate gurus and planners whose contributions created the playing field of modern New York. While it’s always nice to relive the 1920s through a lens of champagne and The Great Gatsby, Miller’s concern is with the players who actually built the city.

The engineer William Wilgus receives deserved placement in Supreme City for his innovations of covering the unpleasant tracks of Grand Central to create acres of new land, “taking wealth from the air” and inventing New York’s ultimate canyon of wealth — Park Avenue.

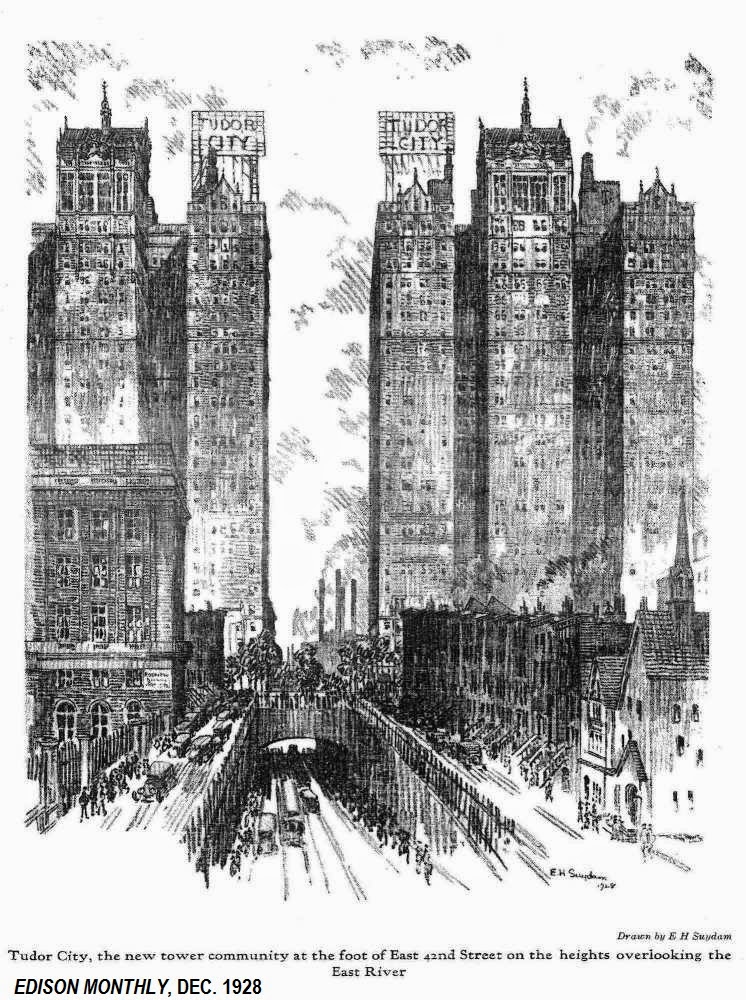

Architect Emery Roth brought the apartment skyscraper to Midtown and practically invented the allure of the penthouse. The almost faceless Fred French — his section is actually called “Who on Earth was Fred French?” — turned the apartment complex into a swanky, thematic thrill with such Midtown projects as Tudor City (a 1928 illustration pictured at left).

Of course, it took the wealthiest New Yorkers to fuel these changes. New money sparked the new playing field. The old families hastened their migration up Fifth Avenue, their mansions abandoned, torn down and replaced with the high-end shops in which they would later shop.

While department store masters like Edwin Goodman swept out the socialites to build his Fifth Avenue temple of commerce Bergdorf-Goodman, the pleasant rivalry between Helena Rubenstein and Elizabeth Arden helped generate the avenue’s reputation of social perfection and high glamour.

Sensing the upward surge of Midtown — its almost-amoral infinite rise — impresarios like Samuel “Roxy” Rothefeld, Florenz Ziegfeld and George “Tex” Rickard rose to create venues to corral the masses. Midtown became home in the 1920s to the industries of entertainment — publishing, radio, television. Even Seventh Avenue below Times Square found purpose in the swell as America’s Garment District.

As Midtown grew in the 1920s, the instruments of getting there also rose to the challenge, finally conquering the Hudson River, from the Holland Tunnel to the George Washington Bridge.

The story is so big that Miller can’t contain all of it. Supreme City captures that place before the Great Depression, perhaps New York’s single most decadent moment. He does not venture out into the other boroughs and rarely even ventures below 42nd Street. From the vantage of the Chrysler Building — the treasure most indicative of the age — those places are hazy and distant. By the last page of this heavy tome, Midtown Manhattan creates everything, drives everything, almost entirely is everything. That energy is certainly infectious, making Supreme City is an rich, propelling read.