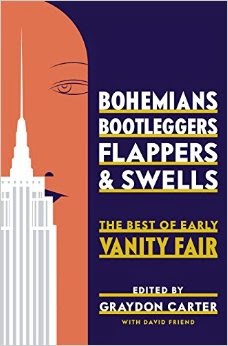

Bohemians, Bootleggers, Flappers & Swells: The Best of Early Vanity Fair

Various authors

Edited by Graydon Carter with David Friend

Penguin Press

BOOK REVIEW  Bohemians, Bootleggers, Flappers & Swells: The Best of Early Vanity Fair sounds like a soirée in book form, but it’s a lot more than that.  If anything, the book’s title is a bit constricting.  The bohemians, the bootleggers, the flappers, the swells — they’ve all brought guests along with them. Welcome!

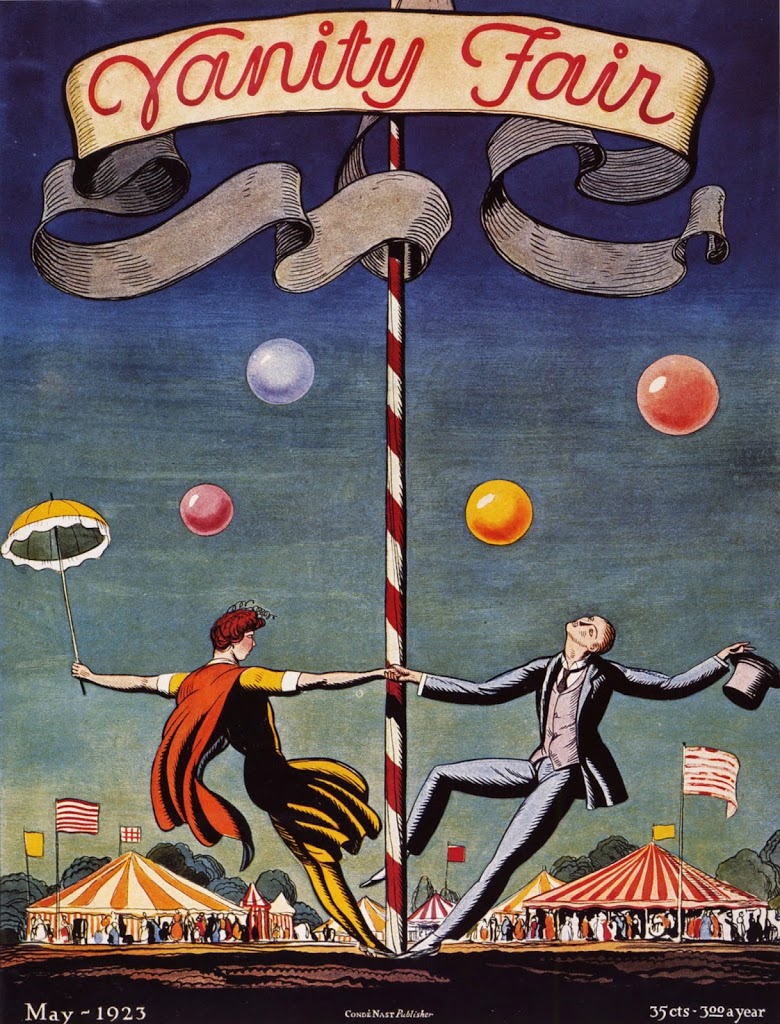

One hundred years ago, Vanity Fair was a men’s fashion and style magazine that gradually became known for some of the best published writing in the world. It was a veritable sounding board for the wits of the Algonquin Round Table whose entire membership either wrote for it or were written about within it.

After the Great Depression, its publisher Conde Nast (the man) folded its contents into his more successful women’s magazine Vogue.

Its spirit was revived in 1983 by publisher Conde Nast (the corporation) and re-energized in the early 90s with the introduction of editor Graydon Carter, best known for the dearly lamented Spy Magazine, which is the closest anyone ever got in the ’90s to the droll swagger of the Algonquin crew.

For its one hundred anniversary, Carter has put together a collection of stories from the magazine’s first incarnation, from P.G. Wodehouse‘s take on the fitness craze of 1914 to Allene Talmey‘s survey of New York nighclubs in 1936. Â The entirety of the Jazz age in contained between them — the fashion, the reverie, the amusement, the agony.

But most of all — the modernity.  If anything defines most of these spectacular entries, it’s the coy observations of change, how America left the Gilded Age to became something awkward but none the less brilliant. In one essay, Aldous Huxley tries to literally define the word: “Let us not abuse a very useful and significant word [modern] by applying it indiscriminately to everything that happens to be contemporary.”

Here are the world’s greatest authors of the early 20th century, attempting to define their era from the vantage of a barstool or a kitchen table.  D.H. Lawrence takes on the modern female, implying she’s merely an update on the ancient woman.  Music critic Samuel Chotzinoff zeroes in on the origin of jazz music in 1923, still in its infancy. Tremors in sports, world affairs, women’s fashion and the stage are all tackled by a rich embarrassment of talents.

We see here the birth of legends at the dawn of their careers, through a variety of writing samples, light fiction to poetry. Â My favorite (no surprise) are the early poems by Dorothy Rothschild (Parker) who beautifully bemoans whole categories of miserable co-workers, in-laws and other species. “I hate actresses/They get on my nerves.” Â Stroll past the entries from T. S Eliot and Gertrude Stein to find an introduction to readers from Carl Van Vechten of the young poet Langston Hughes. Â “Hughes has crowded more adventure into his life than most of us will experience.”

Modern Vanity Fair is known for personality profiles, and there are many on display here. Â Most of the subjects themselves are scarcely quoted themselves; instead their images are preened and paraded by imminent writers and colleagues.

Actor Douglas Fairbanks Jr writes about his wife Joan Crawford (at left)Â in a 1930 essay. “She is intolerant of people’s weakness. Â If someone does her a wrong she is slow in forgetting it but when she does there is no doubt of her attitude. (Fairbanks and Crawford divorced three years later.) Â Alexander Woollcott waxes poetically about the unpoetic Harpo Marx. Â Paul Gallico turns Babe Ruth into a proto-Superman. “He rose from Rags to Riches. Sink or Swim. Do or Die.”

Moments of great foresight rise throughout the essays. Walter Lippman predicts the entire Internet age in his essay on publicity:  “It may even be that when men have lived for a few more generations … the race will no longer have any prejudices in favor of privacy.  They may enjoy living in glass houses.” David Cort‘s post-mortem on the stock market crash of 1929 reads like cynical analysis from 2008.  “Those who recanted, who sold out and are bankrupt, have already been forgotten.  Wall Street wants fresh money, fresh optimists.”

Also included here is Anne O’Hagan‘s defiant laundry-list of woman in 1915 who make more than $50,000. Â “Consider the growing horde of decorators,” she says in one refrain.

Virtually every major name of the arts and letters makes a brief appearance in Bohemians, Bootleggers, Flappers & Swells. Â The collection’s tremendous breadth in subject matter makes it sometimes difficult as a straight-through read, but I would encourage you try it anyway. Â In total, this is as much a story about America between the Great Wars as any actual historical tome.

Virtually every major name of the arts and letters makes a brief appearance in Bohemians, Bootleggers, Flappers & Swells. Â The collection’s tremendous breadth in subject matter makes it sometimes difficult as a straight-through read, but I would encourage you try it anyway. Â In total, this is as much a story about America between the Great Wars as any actual historical tome.

And a quick note about my two favorite stories.  If you only know E.E. Cummings (at right) from his poetry, then you have a treat in store here in a short humorous narrative from 1925 which begins with the sentence, “Calvin Coolidge laughed.”

And then there’s “An Afghan In America,” written in 1916 by Syyed Shaykh Achmed Abdullah, a brief and beautiful tale about old traditions as they play out in a New York ballroom. Â “He danced with her for the rest of the evening. Â He did several new steps. Â He also drank forbidden spirits. Many of them.”

Vanity Fair covers courtesy Conde Nast Publications

Previous recommendations from the Bowery Boys Bookshelf:

1 reply on ““Bohemians, Bootleggers, Flappers & Swells”: What a party! Courtesy Vanity Fair and the toasts of the Jazz Age”

I ordered the book, primarily for the story by e. e. Cummings. One of my favorite poems of all time is the final one from his “Is 5” which begins “if I have made,my lady,intricate.” If you can find it read it. It is beautiful.