Skyscrapers feel like constructs of the modern age because their appearances are constantly evolving — from Frank Gehry’s 76-floor twisty, silvery rocket at 8 Spruce Street to the elegant glass monolith of One World Trade Center.

But buildings with ten or more floors are an invention of the Gilded Age. Skyscrapers are older than subways, recorded music, and the cinema. And a concise new show at the Skyscraper Museum in Battery Park City — Ten & Taller: 1874-1900 — excellently lays out New York’s contributions to the form.

The subtitle to the show is key — “Mapping all Manhattan buildings ten stories or taller by use and date.” The show is a living catalog come to life. Or rather, a living map, specifically this one, illustrating the development of every tall building in Manhattan up to the start of the 20th century.  The show is based on the research of structural engineer Don Friedman who organized this special group on Manhattan structures (252 in all) in chronological order here.

Central to the exhibition is a gloriously massive map of Manhattan,  arduously stitched together from dozens of map plates derived from the 1909/1915 G. W. Bromley and Co. Atlas of The City of New York. This alone is worth the price of admission. If you are a map junkie, just the scale of this impressive work may distract you from subject at hand.

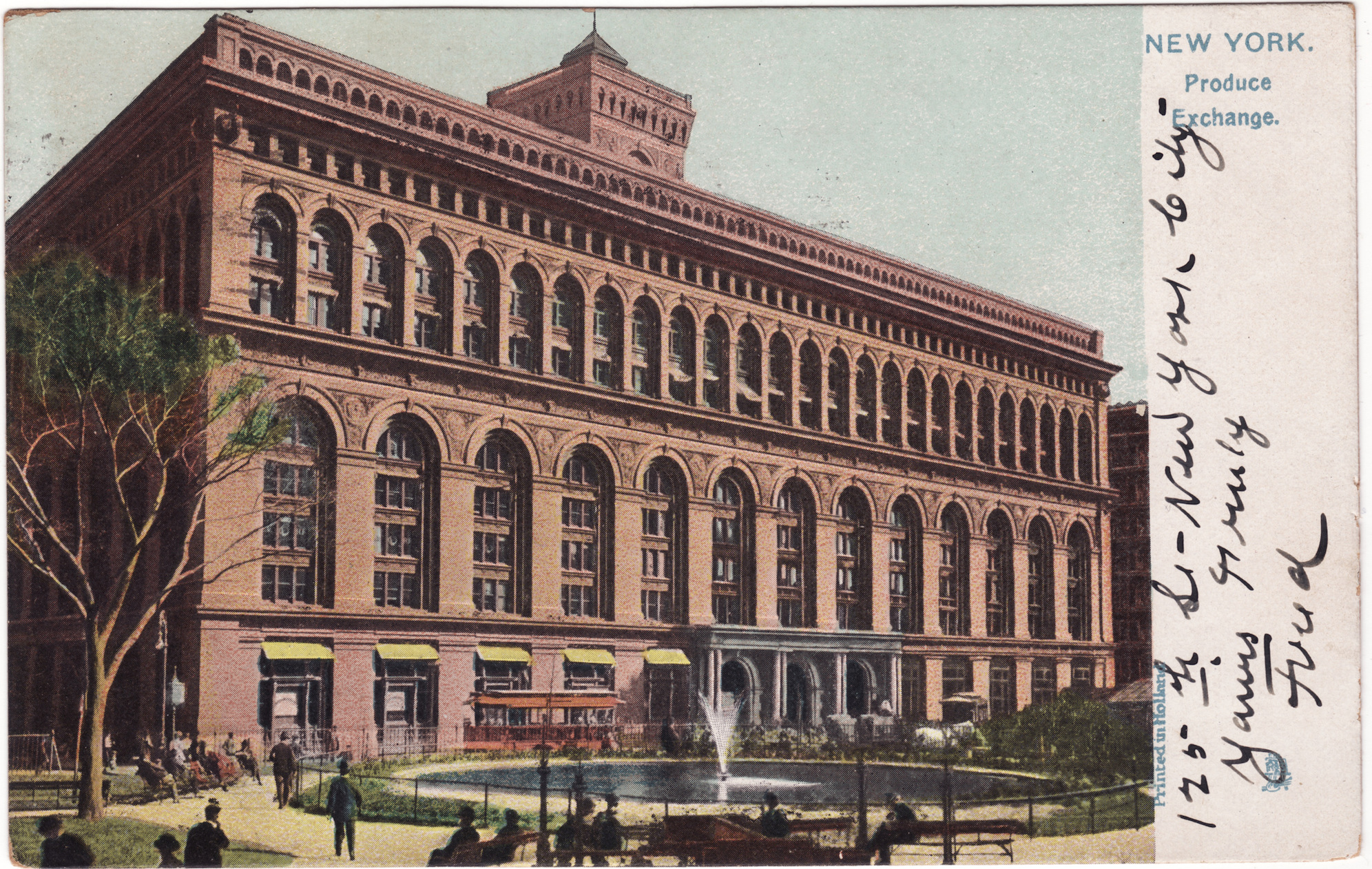

Below: George Post’s Produce Exchange Building (1884-1957) which once sat near Bowling Green.

By studying this map, two facts about New York’s earliest skyscrapers will become obvious — 1) they weren’t merely a lower Manhattan phenomenon, and 2) builders sure loved to line Broadway. Animated maps like this one slowly fill the vast expanse of Manhattan with blips representing the presence of a new skyscraper.

Observing development overhead like this reveals vast numbers of new works, from the tip of Manhattan to the area around the American Museum of Natural History.

Below: The far less glamorous side of the Dakota, 1899

The Dakota Apartments, one of the most northerly contributions, may not strike you as a skyscraper per se.

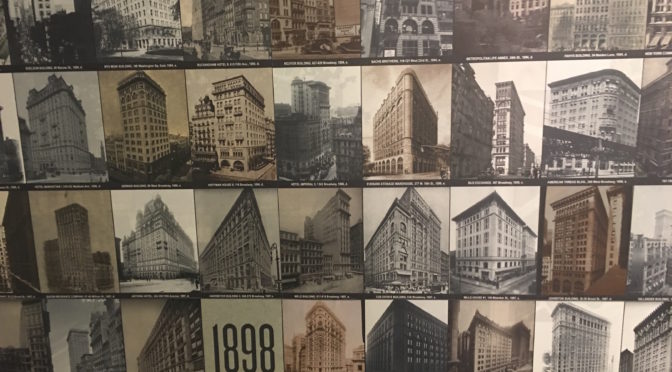

One wall of the exhibit lines up most of these tall buildings like a rogue’s gallery, and the overall effect is striking. Most ten-story buildings of this period, whether masonry or steel-frame construction, weren’t built to feel tall.  Many are ornamented in the Beaux-Arts style, the sort of decor seen more frequently on shorter buildings.  A design language specific to skyscrapers was yet to be developed.

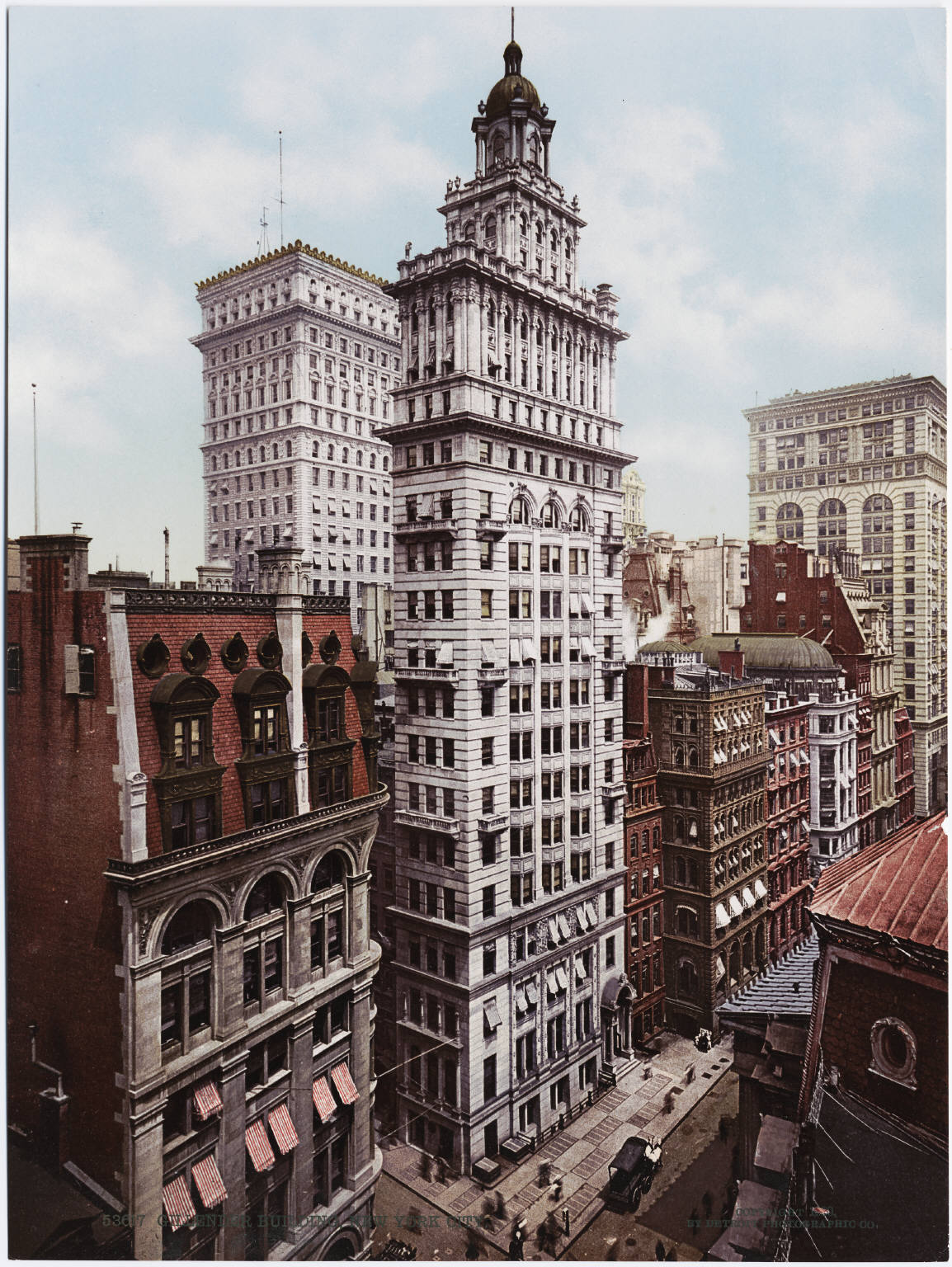

Below: The sleekest of the pre-1900 buildings often shot up from small lots like the ones featured in this display.

In addition, the exhibit focuses on one particular building — the Havemeyer Building, a 14-story skyscraper constructed in 1892, once located on Church Street — presenting massive blueprints to illustrate the grandiosity of its architect George B. Post. Nearby displays offer models revealing the evolution of building techniques up to steel-frame construction, finally allowing buildings to reach higher into the sky.

You’re certain to find at least one odd, long-departed building to fall in love with. Â I was personally enamored by the Gillender Building, a short-lived marvel so slender that it was virtually useless. What a very curious (and very beautiful) use of space.

Visit the Skyscraper Museum website for more information.  The museum is located in lower Manhattan’s Battery Park City at 39 Battery Place, near the Museum of Jewish Heritage. Museum hours are 12-6 pm, Wednesday-Sunday.  General admission is $5, $2.50 for students and seniors