There are several enemies in Candice Millard‘s Destiny of the Republic, the terrific 2011 narrative history of the assassination of President James Garfield during the summer of 1881.

The most obvious foe is the delusional Charles Guiteau, who believed himself the nation’s savior when he shot President Garfield twice at a Washington DC train station on July 2, 1881.

Then there were the microbial infections transmitted during improperly sanitized operations performed by Garfield’s doctor at the White House, causing blood poisoning that worsened the president’s suffering and ultimately killed him.

For the purposes on this website, however, I was drawn into the tales of two New York politicians who became victims of rumor-mongering that summer.

Boss of the Gilded Age

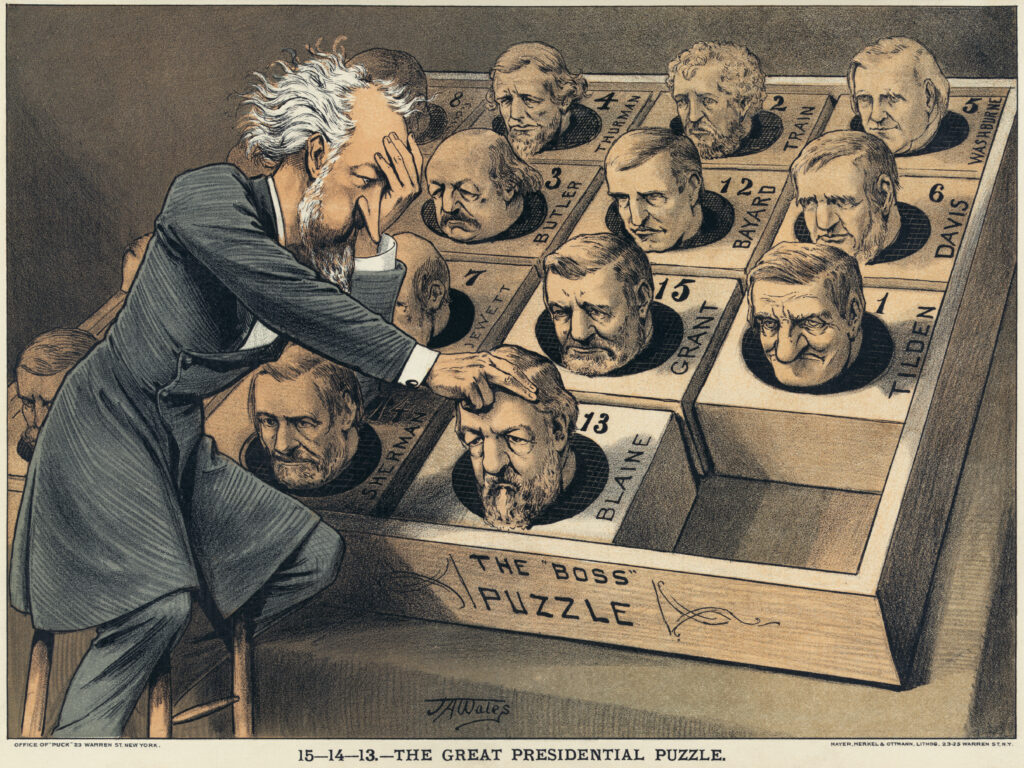

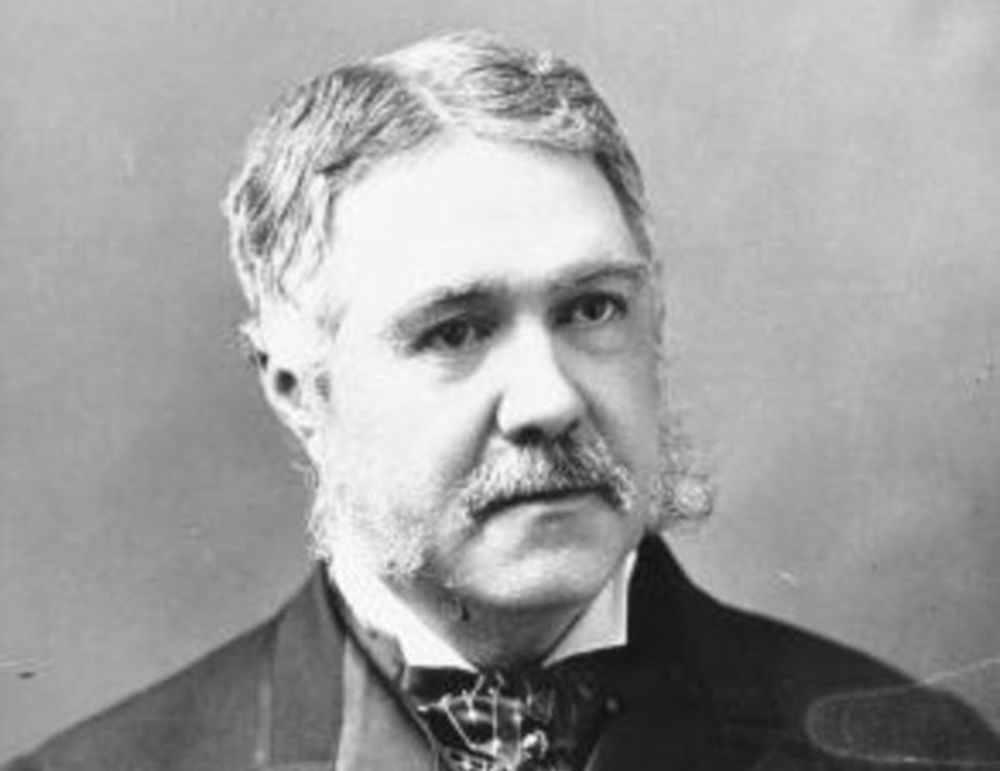

Powerful New York senator Roscoe Conkling was seen as a political rival of Garfield’s, a thorn in the president’s side, especially considering Conkling’s own political protege — his pawn, really — was Garfield’s vice president, Chester A. Arthur.

Traumatic crises in this country are frequently accompanied by a churning undercurrent of suspicion and conspiracy, and Conkling and Arthur became victims of just such a shadowy accusation that summer.

Many believed Conkling to be culpable of the assassination attempt himself — perhaps not of pulling the trigger, but of fostering and encouraging the discord that inspired it.

It’s not a stretch to consider Conkling an embodiment of the spoils system which determined hundreds of government jobs through political affiliation. Guiteau thought himself unfairly left out of that patronage system when he attacked Garfield that hot July day.

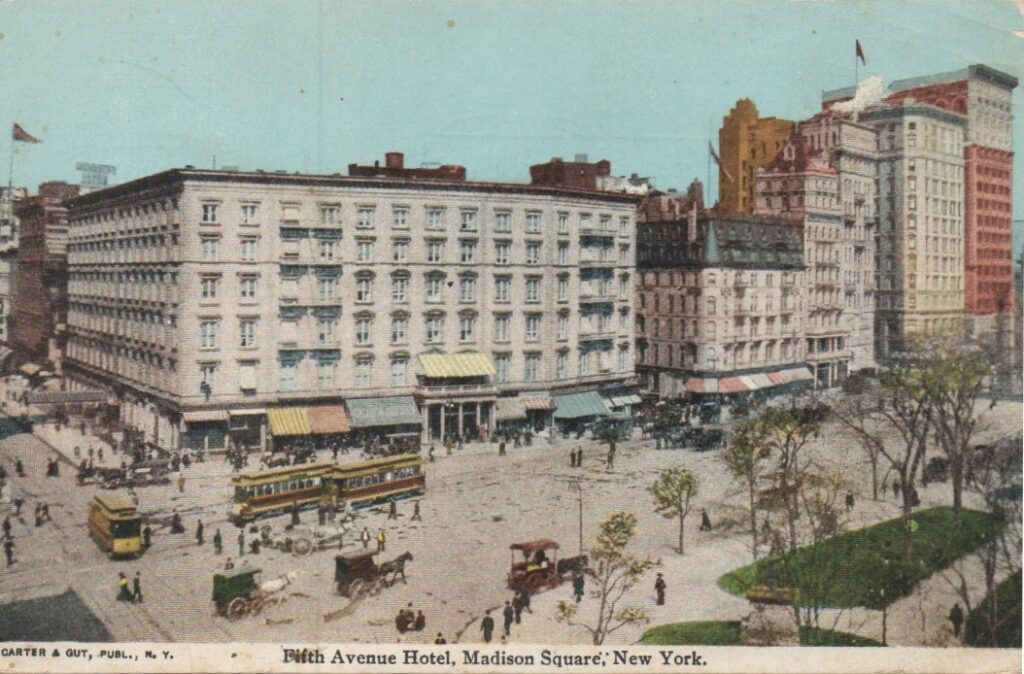

Conkling endured the disintegration of his political career from his rooms at the Fifth Avenue Hotel, the luxury accommodation at 23rd Street off Madison Square that became senator’s second home and a regular scene of political intrigue for the Republican Party.

Arthur in charge?

Meanwhile, many were mortified at the very thought of Arthur, hardly a universally admired figure, ascending to the presidency.

While the president lay incapacitated in Washington, there was even debate as to when presidential responsibilities should cede to the vice president. Nobody seemed enthusiastic at the prospect of a President Chester A. Arthur.

Thus, Arthur essentially spent his summer hiding out in his townhouse at 123 Lexington Avenue (below), fearful of seeming overly ambitious even as the fate of President Garfield seemed uncertain.

The Presidential Brownstone

On the day the president finally succumbed to his injuries, Arthur sobbed uncontrollably from his shuttered home as servants shooed away the press.

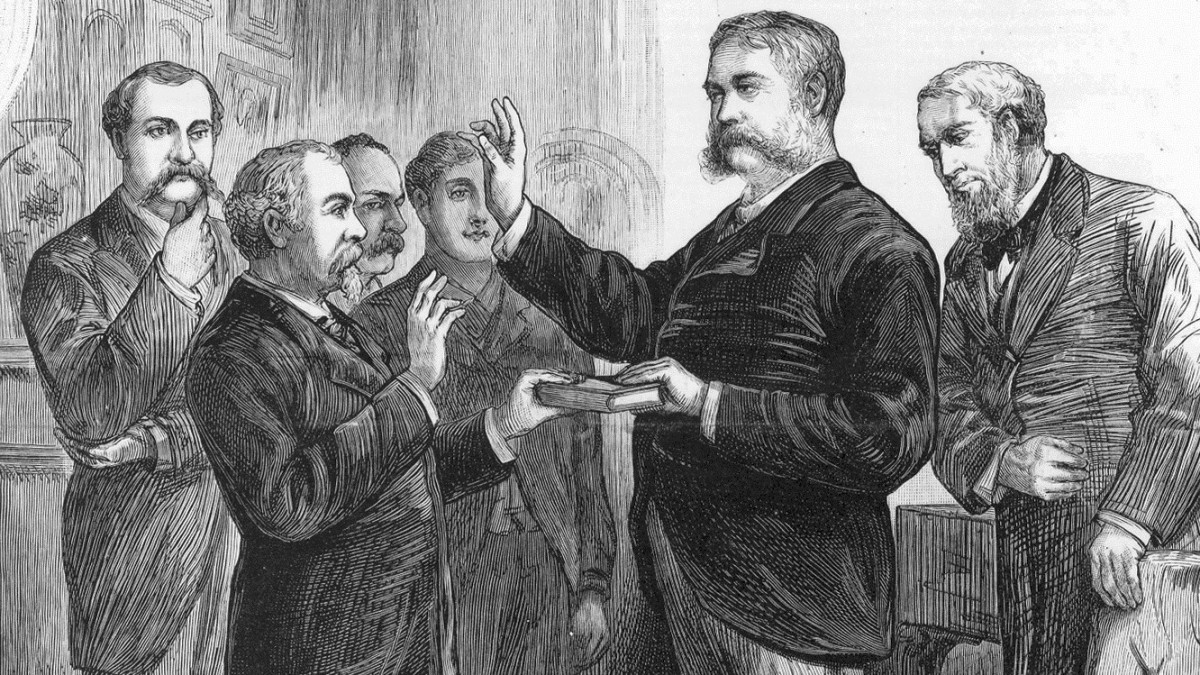

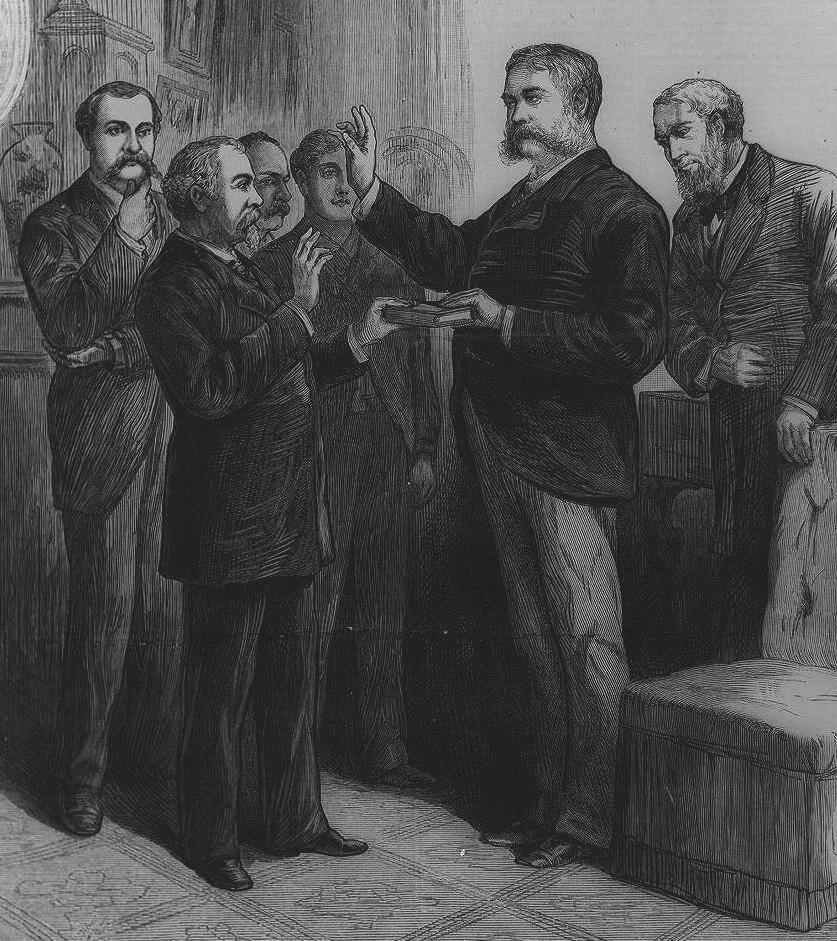

Several hours later, he was sworn in as the 21st President of the United States on September 20, at 2:15 a.m, from the green-shuttered parlor of his home here.

To quote from an excellent biography of Arthur The Unexpected President by Scott S. Greenberger:

“Judge R. Brady of the New York Supreme Court, who had been fetched out of bed, administered the oath of office at 2:15 am. Arthur recited the words solemnly, kissed his son, and accepted the congratulations of his friends. There were several carriages and a handful of reporters outside Arthur’s brownstone, and French had ordered two police officers to patrol the sidewalk in front. Otherwise, there was nothing to indicate that history had been made behind the closed blinds of 123 Lexington Avenue.”

He spend his first two hours as President smoking and chatting with friends, “[t]oo nervous and too excited to sleep.” He finally went to sleep at 5 am, the first morning of his presidency.

The brownstone at 123 Lexington Avenue still exists today. For decades, the Mediterranean grocer Kalustyan’s has inhabited the first two floors of the building.

And this is not the only landmark to Arthur in the neighborhood. A bronze statue to the former president stands in the northeast corner of Madison Square Park, dedicated on June 13, 1899.

The reaction to the president’s death in New York City is reported here in the New York Times. This article originally ran on September 20, 2017.