So how do you follow two journalists around the world, in opposite directions and from the vantage of almost 125 years in the future? I asked Matthew Goodman, the author of “Eighty Days: Nellie Bly and Elizabeth Bisland’s History-Making Race Around the World,” this month’s Bowery Boys Book of the Month, about the two competitors and the challenges of Victorian era travel.

Bowery Boys: So just how insane was it for a woman to travel alone around the world – not to mention two women, going in the opposite direction? How many traditions of propriety were they shattering by accomplishing this?

Matthew Goodman: By 1888 Nellie Bly had established herself as a star reporter for The World, Joseph Pulitzer’s widely read newspaper. But when she went to her editors to propose a solo race around the world to beat Phileas Fogg’s eighty-day mark, the idea was soundly rejected.

This was a time, after all, when male newspaper editors didn’t feel comfortable sending their female reporters across the city, much less around the world. Editors didn’t think it was appropriate for a female reporter to go out by herself out night, or in the rain, or into tenements or dancehalls or barrooms or wherever else a story might lead them, much less consort with criminals and policemen and other unsavory characters. Such behavior was considered improper, undignified, unseemly – in a word, unladylike.

Moreover, any woman attempting to travel around the world would surely require a battery of steamer trunks, to carry all of the ball gowns and so forth that, of course, she would require. And so, when Bly proposed her trip, The World’s business manager told her firmly, “Only a man can do this.†(To which Bly just as firmly replied, “Very well, then. Send your man, and I will start the same day for some other newspaper and I’ll beat him.â€)

A year later, when The World’s circulation had started to decline, Bly’s editors finally gave her permission to set out around the world. To do so, Bly insisted on carrying everything she would need for her trip in a single handbag, measuring sixteen by seven inches at its base. Not only did she want her travel to be as efficient as possible, she also wanted to give the lie to the time-worn notion that a woman required more luggage to travel than did a man. (That leather bag would eventually become iconic, and today it is on public display at the Newseum in Washington, D.C.)

BB: Nellie Bly is of course a classic figure of the Victorian era but Elizabeth Bisland is relatively unknown. Were there any challenges in bringing Bisland’s tale up to the pace of Nellie’s – the more familiar of the two tales?

MG: I knew right from the beginning that I wanted this to be a double narrative – half of it told from Nellie Bly’s point of view, half of it from Elizabeth Bisland’s. Which meant that Bisland’s story would need to be just as richly detailed and compelling as Bly’s – a challenge, as you point out, given that no one had ever written any substantial account of her life and she is today almost entirely unremembered.

So I set to work attempting to learn everything that there was to know about Elizabeth Bisland. Fortunately, Bisland had written a book about her race around the world (as had Bly), so I read that first. Then I read everything else she had ever written – which included a novel and several collections of essays, as well as many dozens of newspaper articles. On the Internet I tracked down a number of her descendants, and they generously shared with me unpublished family histories, letters, photographs, and newspaper clippings about their beloved ancestor.

At left: Elizabeth Bisland, from her book written about her journey called A Flying Trip Around The World

At Tulane University I discovered a little-known trove of Bisland’s letters from the last years of her life, which filled in a lot of details that even her family members didn’t know. Over time I was able to develop a very strong sense of who this remarkable woman was; as it turned out, she was this incredibly erudite, cosmopolitan poet and essayist who had grown up on a ruined Louisiana plantation (where, for instance, she taught herself French as she churned butter so that she could read Rousseau’s Confessions in the original language!), who wrote gorgeously but whose books are all, sadly, out of print.

She is someone who deserves to be far better remembered than she is, and if Eighty Days can bring her to the attention of a new generation of readers, then I’ll be extremely gratified.

Above: One of dozens of issues of the New York World that used Bly and her adventures to sell papers — before, during and after the race!

BB: The two travelers take nearly the very same path across the world, from opposite directions of course. I love the exact moment in the book where their paths cross (although of course they never realize it). Were Bly and Bisland driven by similar desires – competition, fame, or the chance to make history perhaps?

MG: One of the things I loved about writing this book was that the two main characters – while both pioneering young female journalists – were so different from each other. Nellie Bly was this scrappy, ambitious, driven investigative reporter from coal country in western Pennsylvania, who always sought out the most sensational news stories; Elizabeth Bisland was a genteel, elegant poet from New Orleans who derided most newspaper reporting as “a caricature of life.†Bisland hosted literary teas in her little apartment on Fourth Avenue; Bly was a regular at O’Rourke’s saloon on the Bowery!

And their very different personalities were reflected in their attitudes toward the race itself. Bly was deeply competitive (it was part of what made her such a good newspaperwoman), and she was desperate to win the race – she was constantly worrying about schedules and departure times, and was constantly urging ships’ captains to make more speed. On more than one occasion she was heard to say that she would rather die than return to New York behind time.

For Bisland, on the other hand, the trip became an opportunity to see the world, which she would not have had otherwise. She fell in love especially with Japan, to which she returned twice later in life. In her subsequent book about the trip, she never once used the word “race†to describe it, preferring the word “journey.†Bly sought out the celebrity that came from the race, immediately embarking on a forty-city lecture tour; Bisland, wanting to escape the public’s attention, sailed to England, where she lived for a year. She later wrote that she wanted to live the rest of her life in such a way that her name would never again appear in a newspaper headline.

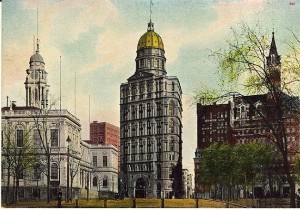

Above: The New York World Building, completed in 1890, the year Bly completed her trip around the globe.

BB: Your last book The Sun and The Moon was about a fabulous New York media hoax. In Eighty Days, the publications in question are in fact recounting real events. But I cannot imagine, given the ethics of the day, that everything you were discovering in them about Bly and Bisland was completely accurate. Did you find anything unusual in your research about these publications’ treatment of the race?

MG: Perhaps not surprisingly, a lot of the initial coverage of the race was rife with mistakes, as New York’s newspapers, caught unawares by the story, tried to pin down just who these two young women were.

For instance, one newspaper claimed, confusingly, that both reporters were being paid by The World (why that paper would send two competitors around the world was not explained). The Tribune even ran a story that claimed that not two but three reporters were racing around the world!

The more substantial inaccuracies, though, were to be found in The World’s own stories about Nellie Bly. Bly and The World jointly participated in a kind of mythologizing of their star reporter, creating an air-brushed portrait of a plucky, independent, light-hearted, pretty, energetic young American woman – just the sort of heroine the paper’s readers wanted. Indeed, the most egregious rewriting of Bly’s history came in a story – surely approved by Bly herself – that promised “an authentic biography of The World’s globe-girdler.â€

BB: There should be a side project where you yourself trace the steps of Bly and Bisland, approximating their forms of transportation (no airplanes!) Is that technically possible and how long do you think it take you – or would you have the stamina of your two heroines?

MG: My sense is that it would be technically possible. (I seem to recall a PBS series of some years ago in which Michael Palin, of “Monty Python†fame, traveled around the world in such a manner and accomplished the feat in just under eighty days.)

It would be possible, however, for someone other than I. I do love to travel, and would very much love to go to many of the places Bly and Bisland visited – such as Hong Kong or Sri Lanka, not to mention Jules Verne’s estate in Amiens, France – but after a few weeks spent aboard ship or in a railway carriage, I’m pretty sure I’d start planning my return to dear old Brooklyn.

1 reply on “A chat with Matthew Goodman, author of ‘Eighty Days’”

[…] Bowery Boys Interview of author Matthew Goodman […]