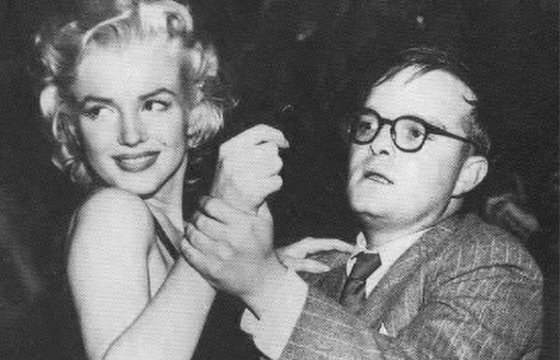

Above: Marilyn and Truman maintain their composure at the Peppermint Lounge, an early 60s dance hole that frequently scoffed at fire codes

Time Out’s cover story last week features places and events where a New Yorker can still go and dance. Very nice try. Dancing in a public place can be akin to performing an illegal act if the establishment does not hold a cabaret license, a permit that can be so difficult to obtain that, as of 2006, only 200 establishments in all five boroughs have one. You can thank the excesses of Prohibition and 1990s club kids, Rudy Guiliani, and maybe even the advent of the iPod as the causes.

For most of New York’s history, recreational dancing split society. The taverns of the Dutch, the freed black population at home on Cow Bay, the Irish basements of Five Points, the naughty brothels of the Bowery — commoners mixed their dancing with liquor and sex, launched marathon parties in the dankest, seediest parts of their neighborhoods. Dancing was an escape.

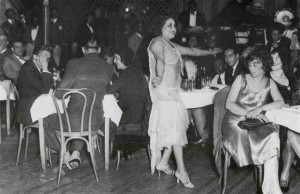

Below: An unrestrained shimmy in Harlem in the days before the cabaret license

For New York’s upper-class, it was anything but. The British took to ballrooms like the New York Arms in 1750, New York’s upper-crust to their formal ‘dance assemblies’ in post-Revolutionary times, and later the elaborate pavilions of Vauxhall Gardens and sumptuous hotel ballrooms. But dancing was a proper, rigid affair, more prone to causing stress than relieving it. Who would dare be comfortable at one of Mrs. Astor’s storied functions, a collection of New York’s 400 and no place to get creative with your fancy footwork? When Alva Vanderbilt threw her legendary $3 million masquerade ball in 1883, musical innovation was not on her mind.

What brought the classes together in the 20th century — musically speaking — was the emergence of jazz and Big Band — Small’s Paradise uptown, the Roseland Ballroom in Times Square, and every nook and cranny in between. What eventually brought them together physically was Prohibition, driving cultural excess into the underground, loosening morals and dance steps, both breaking couples up to enjoy the pleasure of dancing alone, and pulling them together in more sexually charged moves.

Below: swinging it at the Savoy

It was at the height of Prohibition that New York debuted its idea of a cabaret license. In 1926, as a way to reel in sanction out-of-control establishments (which were often discreetly selling liquor), the state required licenses for any place that wished to host “three or more musicians” especially “any … percussion or brass”, or “three or more people moving in synchronized fashion.”

The real motive behind the laws were probably a lot more sinister; the new nightclubs were bringing classes together, and that meant bringing races together. Whites mingled with blacks up in the swanky Harlem clubs and down in the Village, at Cafe Society and smoky coffeehouses.

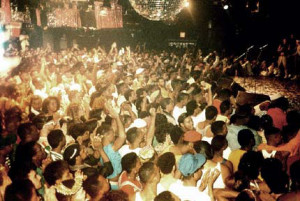

Below: Packed in at the Paradise Garage

By the 1980s, musicians were exempted from the cabaret license — could you imagine such a restriction on percussion today? — but the dancing ban stayed on the books. The restriction did little to squelch the spread of disco, funk and hip hop, and dance music flourished in the 70s and 80s, partially because they were genres that derived as much from the street as from set establishments.

Controversies over the cabaret license reared again during the administration of Rudy Guiliani, whose quest to scrub clean the city ran headlong into the decadence nightclub culture of the 1990s. By this time, drugs ran rampant through the halls of Peter Gatien and the elaborate super-clubs of the west side. Cabaret law enforcement had also laxed, and even gigantic clubs catering to thousands of people failed to get them. In 1996, Guiliani created the Nightclub Enforcement Task Force, and the bubble burst. Dozens of clubs, big and small, were busted, ostensibly to curtail the rampant drug culture.

Or as the Gotham Gazette says, “Some blamed the owners themselves, for refusing to address the problems emanating from their clubs, and failing to cooperate with the authorities. Others said the police overreacted.”

The current process of obtaining a cabaret license can be compared to, say, the many obstacles faced by Odysseus. However, it’s not technically impossible.

The bigger buzzkill to the New York dance scene is general lethargy combined with raising rents. The gigantic dance spaces of old are simply too big to keep empty. Many old club have become condos or office buildings. One, the Palladium, became a New York University dorm. Paradise Garage is a Verizon warehouse. Others stay in the world of entertainment, but change the tune — Studio 54 is a theatre, Exit is a live music venue (under the name Terminal 5)

And is there room for public dancing if the iPod inspired “silent raves” become popular? Ugh!

But perhaps things are changing. One potentially symbolic move was reported yesterday by amNew York’s Urbanite blog: the Roxy, one of New York’s disco icons, may be reopening after rumors that it shut its doors last year to become condo-land. Can the beat come back to New York?

Below: The club Stereo, surviving through a series of closings and re-openings, was gutted by a fire a couple weeks ago. (Pic courtesy of Queen of New York)