We’re just a few weeks away from a new mayor in New York City so we think it is time that you Know Your Mayors! Become familiar with other men who’ve held the job, from the ultra-powerful to the political puppets, the most effective to the most useless leaders in New York City history.

This longtime feature of this website is being rebooted with new articles and newly researched and refreshed earlier entries in this series. Check back every other week for a new installment. Read past articles here.

Philip Hone

Term: 1826-1827

Many of our city’s early mayors are marginal figures obscured by a lack of personal information contained in publications of the day.

We only know a few by their actions and can only indirectly discern their personalities from their popularity and effectiveness.

Not so with Philip Hone, the Whig mayor of New York City for a single solitary term (1826-27).

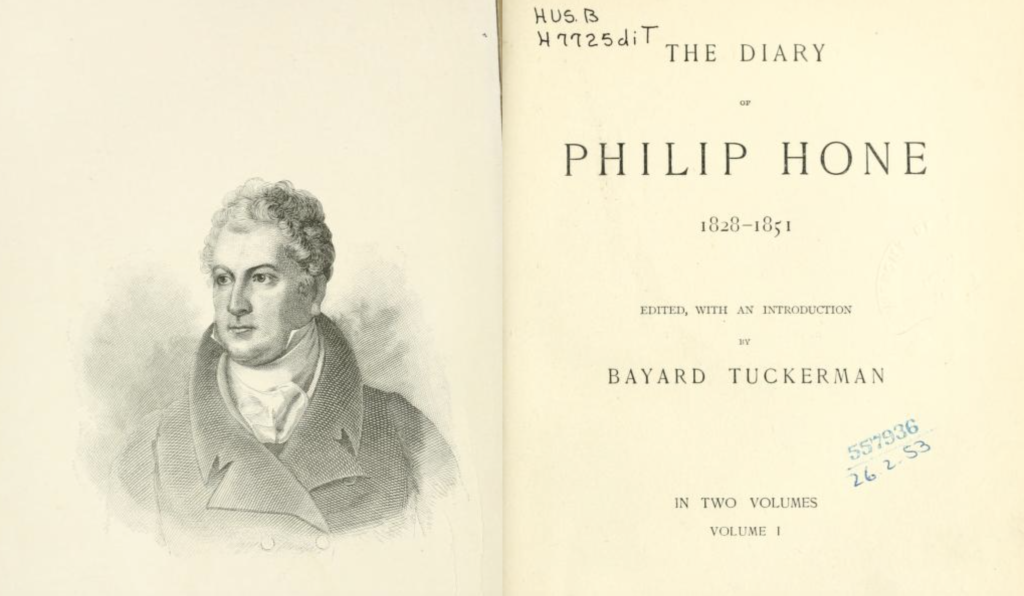

Thanks to his fascinating and well written diary, we not only know all about him, we have an uncommonly vivid window into the workings of the early city.

Twenty-Four Hour Party People

Hone was born in 1780 on Dutch Street (between John and Fulton streets) and made his name on the nearby ports as an teenage auctioneer selling goods right off the boat.

His auction business became known throughout the ports of the new America, and by age 40, the self-made Hone had amassed such wealth that he effectively retired to the life of a “gentleman”.

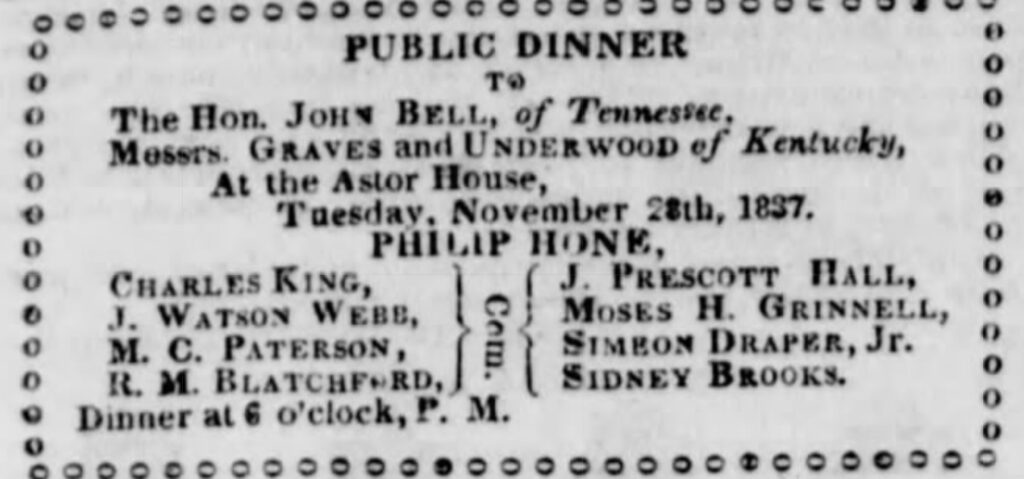

From his lavish home on 235 Broadway across from City Hall, Hone dined with politicians and celebrities, a good-natured and cultured bon vivant, an old school Knickerbocker who would consider himself good friends with the likes of Daniel Webster, Washington Irving, and John Jacob Astor (whose Astor House would sprout up next door).

His parlor hosted a nightly gallery of political and foreign dignitaries mixing it up with New York’s social strata.

From his diary: “As his children grew up the house became a resort for the young people ; and it was an ordinary question for the beaux and belles walking on Broadway : ” Shall we meet to-night at Mr. Hone’s, or at Dr. Hosack’s?” — these being the two houses in town most constantly open..”

Naturally, political ambitions also came knocking, and Hone was elected an alderman in 1824 before winning the mayoralty in 1826, a rare representative of the Whig party in a city ever so dominated by Democrats.

It seems that Hone’s strengths as mayor came as a direct extension of his role as New York’s social network king. He’s as known as much for his parties as for his policies.

King of Clubs

The introduction to his diaries doesn’t even bother to disguise this: “Mr. Hone represented the city socially as well as politically. He entertained officially; and visiting strangers during his term enjoyed a hospitality which reflected credit upon the whole community.”

A true social butterfly, he amassed membership in a variety of clubs and associations, became a trustee in New York’s first insane asylum, and dabbled early in canal building as president of the Delaware and Hudson Canal company (later to become the basis of the D&H Railroad).

“He was never voluntarily absent from a meeting where the interests of others demanded his presence, and many were the good dinners which he lost in consequence.”

As a comfortable and well-connected gadabout, his somewhat elitist views and political outsiderness left him stranded in a city where ‘Whiggery’ often equated only to upper classes.

In particular his anti-Irish, anti-Democratic positions were fighting against the wind. Later, by the 1830s, the power struggles between Whigs and Democrats would virtually wipe Hone’s party from the city’s political map.

Mostly, he’s remembered as a cultural ambassador, even commissioning artwork for City Hall, approving of a developing theater district in the not-yet-seedy Bowery and encouraging the city’s growth as an American capitol of arts and sciences.

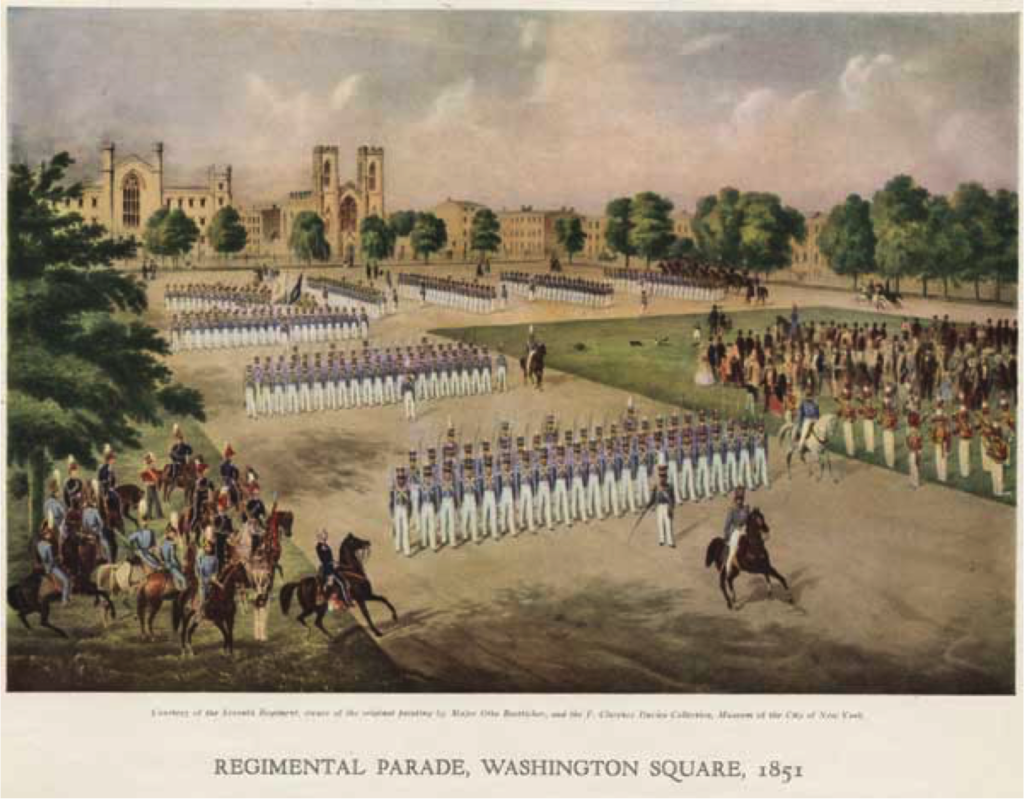

The Washington Parade Ground

But he’s largely responsible for one of New York City’s most beautiful places — Washington Square Park.

Hone, as earlier mentioned, was on the board of everything. One of those organizations was Sailors Snug Harbor, a retirement home for “aged, decrepit, and worn out seamen” which owned property immediately north of New York’s public burial grounds in Greenwich Village.

By 1831 the retirement home had moved to the donated farmland of Robert Richard Randall on the north shore of Staten Island (where it resides to this day). To raise money for the organization, Hone suggested that the former burial ground — which was already overcrowded — be transformed into a military parade ground.

“Hone ensconced the militia in the former potter’ field,” wrote Luther S. Harris in his book Around Washington Square, “then decreed that the site be used to host the national jubilee for the fiftieth anniversary of the signing of the Declaration of Independence.”

In June of 1826 the grounds were renamed the Washington Parade Ground, in time for a massive jubilee celebrating that patriotic anniversary the following month. As a result this meant that Sailor Snug Harbor’s Greenwich Village property became much, much more valuable.

By the end of his term, the ‘parade ground’ would be expanded to its present size. The military would leave the grounds by the late 1840s and it would be renamed Washington Square Park.

Diary of a Comfortable Man

As for Hone, his true claim to fame would come as an urban observer, not only as a civic leader.

He was replaced as mayor with William Paulding, the mayor with the famous brother (and subject of the last Know Your Mayors installment).

Moving to the “south-east corner of Broadway and Great Jones street” above Houston Street, where he would remain until his death in 1851, Hone would document in a remarkable diary the everyday, upper-class life of New York, from political shifts to the latest opera.

Hone’s “graphic pen”, as described in a New York Times review in 1896, would become one of the great chronicles of early New York history, a “naive, faithful and vastly interesting record of social, commercial and political events here ” and in Europe.” [source]

From his diary introduction:

“Mr. Hone took pleasure in recording the events which took place under his eyes during the first half of the present century. He saw New York grow from a town of twenty thousand inhabi- tants into a city of five hundred thousand ; he saw the residence portion of the city extend up Broadway to Union square, up Fifth avenue as far as Twentieth street. And in this enormous growth and all the changes which it involved, he had borne an influential part.”

Most notable is his description of the terrible Great Fire of 1835, a tragedy which momentarily gutted the high society he had fostered for years:

“How shall I record the events of last night, or how to attempt to describe the most awful calamity which has ever visited these United States? [It was the] greatest loss by fire that has ever been known, with the exception perhaps of the conflagration of Moscow, and that was an incidental concomitant war….”

The diary is indispensable for New York historians. You can take peek at the 1889 edition here.

This article is an expanded and reedited version of an article which first ran on this site in 2008.

5 replies on “Mayor Philip Hone, the party host who made Washington Square Park”

I, too, am not sure if the entire Hone diary is in print, but portions of it were printed in a collection titled “The Hone & [George Templeton] Strong Diaries of Old Manhattan”, edited by Louis Auchincloss and published by Abbeville Press in 1989. A truly amazing read.

QUESTION: once upon a time along the Bowery, there was an establishment called “THE GAIETY” (which I’ve seen in those old stereoview photos). Do you know which would be the closest cross streets on the Bowery where The Gaiety was located? Thanks. Come up and see Mae . . . MaeWest.blogspot.com

Hone was my great great uncle? I am named after him. My great grandmother’s name was Cora Hone!

I was named after Philip Hone as my great grandmother was a Cora Hone, I would be Philip Hone’s great great uncle?

Does any one know how the Hones ended up in Hastings Minn?