(The imposing Front Five, a wall of Greek revival madness, faces the Kill van Kull and Richmond Terrace almost like a fort.)

Although the sailors home that eventually became Snug Harbor was not in the location its founder Robert Richard Randall would have preferred, it quickly became as tranquil and as restful a place as any rest home might in the 19th century. Fortunately many of the buildings have been completely restored to their original charm, and in some cases (see below) even more so.

You might be asking about now — why would I want to walk around an old rest home? Its all about that mix between careful preservation and vibrancy. Snug Harbor is both a throwback and a modern facility that very rarely feels stodgy. Many similar landmarks would do well to take some lessons from here.

The Minard Lafever-designed hall “Building C”, housed in the the center structure of the Front Five, is the most dazzling architecturally, built in 1830-1, with a wide Victorian entrance way and blue glass windows on the second floor. Building C is generally considered Lafever’s greatest still-existent building.

Unfortunately the building is darker than the rest, so my sad little digital cam can’t begin to capture the beauty. On top of well preserved rooms with historical displays, the building also hosts the Newhouse Gallery, featuring contemporary art displays.

(You can click on any photo to see detailing)

The smaller but no less impressive Building D (can’t they come up with more nautical names?) next door is of more interest to history lovers. With its white wood floors and flawless well-lit restorations of rooms and stairwells, the building is virtually laminated. It’s here that you can get a taste of what living at Snug Harbor might have been like.

Here were some of the former residents of Sailors Snug Harbor, world weary faces that survived decades at sea to spend their final days at Snug Harbor. One of the earliest governors of Snug Harbor was no less than Herman Melville’s brother Thomas, who was reputed to be a bit of a hardass with his aged charges.

Building D, built in 1841, serves as the Noble Maritime Collection as well and features artifacts from ships that frequented New York harbor and Staten Island.

Okay, so its not exactly four star accommodations, but given that the men housed here were used to cramped sea quarters for most of their lives, rooms like this must have looked spacious. The skillful design of the building allows for natural light to spill in everywhere.

The Maritime collection is named for John Alexander Noble, one of America’s foremost nautical painters. It was in part to his efforts that Snug Harbor was saved from the wrecking ball in the early 70s. Restoration of the building actually started as a space for his artwork.

Down this beautiful (and, let’s face it, Shining-like) hallway lay a presentation of Noble’s life and work:

Born in Paris in 1913, Noble spent his life in New York working on schooners, and became particularly entranced with a boatyard of docked and abandoned vessels at Port Johnston, at Bergen Point, New Jersey. His father was an accomplished painter and apparently passed on his talents to his curious and contemplative son. Enamored of sea life and particularly those used, beaten ships, Noble built a houseboat out of salvaged pieces and made himself an artists studio there, become a full time artist in 1946.

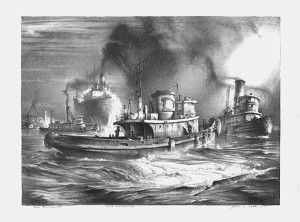

Many of the works displayed in Building D are Noble’s inspirations from taking a rowboat and touring the shores of Staten Island, taking in the activity of the ports and visiting ships.

Snug Harbor is as complete a monument to a single artist as you’ll be likely to find. Noble’s houseboat has been meticulously transferred to one of the building’s hallways:

Inside the houseboat, his studio has been dutifully recreated:

A haunting example of Noble’s work:

The 20th century saw a drastic improvement in social security and health benefits for the elderly, opening options for retired seamen. Enrollment into the home fell from 1,000 men in 1900 to just 110 by the 70s. The firm in Washington DC has actually proposed demolishing all of Snug Harbor’s “obsolete” buildings but Building C. Vicious battled ensued between the city and trustees (who wished to demolish and build new facilities) before landmark status was finally granted in 1976. The sailors (and St Gauden’s statue of Robert Randal) were shipped to North Carolina, and Snug Harbor Cultural Center was opened to the public in 1976.

Modern Snug Harbor can give some thanks to an unlikely source: Jacqueline Kennedy Onassis, who became an early supporter of preserving the grounds as is. “Attention should be brought to a place like this. There’s no place in all the five boroughs where there is such a sanctuary as this…it must be preserved.” She would certainly be pleased with its modern incarnation.

Tomorrow: modern Snug Harbor, home of art, gardens, massively gigantic bugs and, yes, that killer brunch

1 reply on “Snug Harbor: a port in the storm (Part 2)”

Well it’s nice to see they kept a tiny flavor of the sailing history— but in their bid to become this Cultural Arts Centre they threw out a lot of the history that is really regretful.

Architecture is great and thank goodness it wasn’t demolished.

There are lots of inspiring places within it, but I would have liked to know more about the men that lived there and their lives sailing.

People don’t really have a clue anymore about what that life was like, and all over Snug Harbor that element seems to have been swept under the rug or polished to blinding gleam, so as not to take away from their focus of striving to be The Lincoln Center on the Bay or whatever.

Believe me, I grew up right there, and have lots of great memories but sometimes Staten Islanders try too hard to be seen as sophisticated and lose the realness of a place.