The villain du jour of the latest financial scandal is investment firm Goldman Sachs, accused of fraud by the Securities and Exchange Commission for misleading investors on the shady details of certain ‘exotic’ mortgage-backed securities.

The villain du jour of the latest financial scandal is investment firm Goldman Sachs, accused of fraud by the Securities and Exchange Commission for misleading investors on the shady details of certain ‘exotic’ mortgage-backed securities.

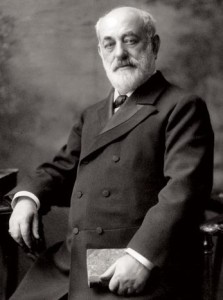

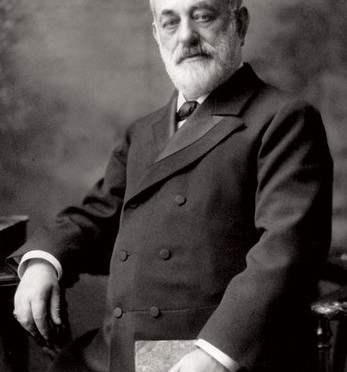

The magnitude of Goldman Sachs’ ambitions over the past 140 years — its seismic up and downs, through booms and recessions — belie its modest beginnings in a basement office next to a coal chute on a small block in downtown Manhattan. It’s doubtful that its founder, Marcus Goldman (at right), would recognize his own company today. Sitting upright on a single stool, well groomed in a Prince Albert jacket, the uniform of New York’s financial class, Goldman prepared to leap into a new venture, the future uncertain. His most important business accessory was a tall, silk hat.

The roots of Goldman Sachs lies within the increasing numbers of German immigrants who came to the United States starting in the late 1840s. There were 100,000 German in New York by 1860 with their own newspapers, schools and churches influencing the city’s cultural identity. Among them were publishers, musicians, bakers, merchants. And lots of bankers.

Early German financiers like Joseph Seligman (later known as the broker of railroad baron Jay Gould) were already established on Wall Street by the time young schoolteacher Marcus Goldman arrived here from Frankfurt in 1848. He started a family in Philadelphia, his wife Bertha employed as seamstress for society ladies while Marcus himself peddled from a horse-drawn cart, later opening his own clothing store.

But it was soon time for some reinvention. Closing his store, in 1869 the Goldmans moved to New York at his wife’s insistence, residing in a Murray Hill brownstone among the families of new wealth. Marcus opened a small business on 30 Pine Street, a small sign “Marcus Goldman, Banker and Broker” barely noticable among the counting houses, book stores and sidewalk trade made up the street parallel to Wall Street.

Goldman’s office was modest indeed, furnished only with a stool and a desk, employing a young apprentice and, according to Stephen Birmingham, “a wizened part-time bookkeeper (who worked afternoons for a funeral parlor).”

It didn’t matter, because Goldman was constantly on his feet anyway. His unique trade was as a broker of IOUs, the at-this-time new busness of commercial paper, transacting between the small merchants of the jewelry and leather trades and the uptown banks. Wandering down Maiden Lane, Goldman would visit the mostly Jewish tradesmen of the area, cultivate their trust and buy their debt at a set rate of interest, shoving notes into his silk hat until it bulged. According to Lisa Endlich, “It was said that a banker’s success each day could be measured by the ‘altitude of his hat’.”

Single-handedly, Goldman was making $5 million a year, keeping his family in finery and a growing number of servants. By 1880, the firm was raking in $30 million. Two years later, he was able to expand his business further by bringing his son-in-law into the fold — Samuel Sachs, son of a Bavarian saddlemaker, who also happened to be friends with one Philip Lehman, whose firm the Lehman Brothers would frequent partner with Goldman’s firm. (And would, 128 years later, file for bankrupsy.)

Single-handedly, Goldman was making $5 million a year, keeping his family in finery and a growing number of servants. By 1880, the firm was raking in $30 million. Two years later, he was able to expand his business further by bringing his son-in-law into the fold — Samuel Sachs, son of a Bavarian saddlemaker, who also happened to be friends with one Philip Lehman, whose firm the Lehman Brothers would frequent partner with Goldman’s firm. (And would, 128 years later, file for bankrupsy.)

The new Goldman Sachs company allowed the two participating families to thrive in New York society. And soon, the lucrative firm would no longer be just a family affair, inviting in partners to become Goldman Sachs and Co. in 1885.

Samuel would take over for Marcus at his death in 1904 and would steer the company’s fortunes until his retirement in 1928, a year before the start of the Great Depression. Its fortunes at that point would be guided by Sidney Weinberg, a former janitor who climbed the corporate later to head the firm in 1930, aiming beyond the business dealings once stuff in Goldman’s hat and towards the wave of the future: investment banking.

1 reply on “Goldman Sachs: things were much simpler then”

Thanks for refreshing my memory! I couldn’t recall from your Wall Street podcast if Goldman was one of the originals!

Also, the word ‘bankruptcy’ is misspelled in your link.