Just south of the World Trade Center district sits the location of a forgotten Manhattan immigrant community. Curious outsiders called it Little Syria although the residents themselves would have known it as the Syrian Colony.

Starting in the 1880s people from the Middle East began arriving at New York’s immigrant processing station — immigrants from Greater Syria which at that time was a part of the Ottoman Empire.

The Syrians of Old New York were mostly Christians who brought their trade, culture and cuisine to the streets of lower Manhattan. And many headed over to Atlantic Avenue in Brooklyn as well, creating another district for Middle Eastern American culture which would outlast the older Manhattan area.

Who were these Syrian immigrants who made their home here in New York? Why did they arrive? What were their lives like? And although Little Syria truly is long gone, what buildings remain of this extraordinary district?

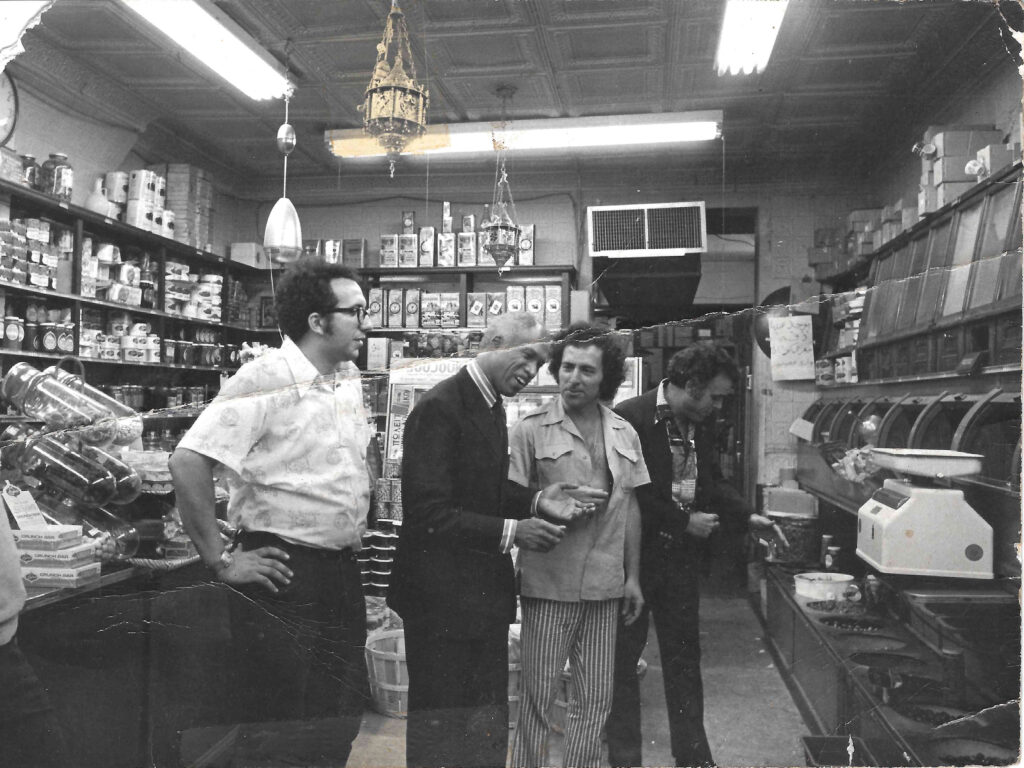

PLUS: A visit to Sahadi’s, a fine food shop that anchors today’s remaining Middle Eastern scene in Brooklyn. Greg and Tom head to their warehouse in Sunset Park to get some insight on the shop’s historic connections to the first Syrian immigrants.

Listen Now – A Visit to Little Syria

Help save one of the last buildings still standing in the former Syrian Colony! Sign the petition to save the Downtown Community House, one of three buildings left standing from this era in New York City history.

Below: St George’s Syrian Catholic Church (now a restaurant)

FURTHER LISTENING

After you’ve listened to this show on the history of New York’s Syrian population, dive back into the back catalog and listen to these shows referred to on the show:

The Bowery Boys: New York City History podcast is brought to you …. by you!

We are now producing a new Bowery Boys podcast every other week. We’re also looking to improve and expand the show in other ways — publishing, social media, live events and other forms of media. But we can only do this with your help!

We are now a creator on Patreon, a patronage platform where you can support your favorite content creators.

Please visit our page on Patreon and watch a short video of us recording the show and talking about our expansion plans. If you’d like to help out, there are several different pledge levels. Check them out and consider being a sponsor.

We greatly appreciate our listeners and readers and thank you for joining us on this journey so far.

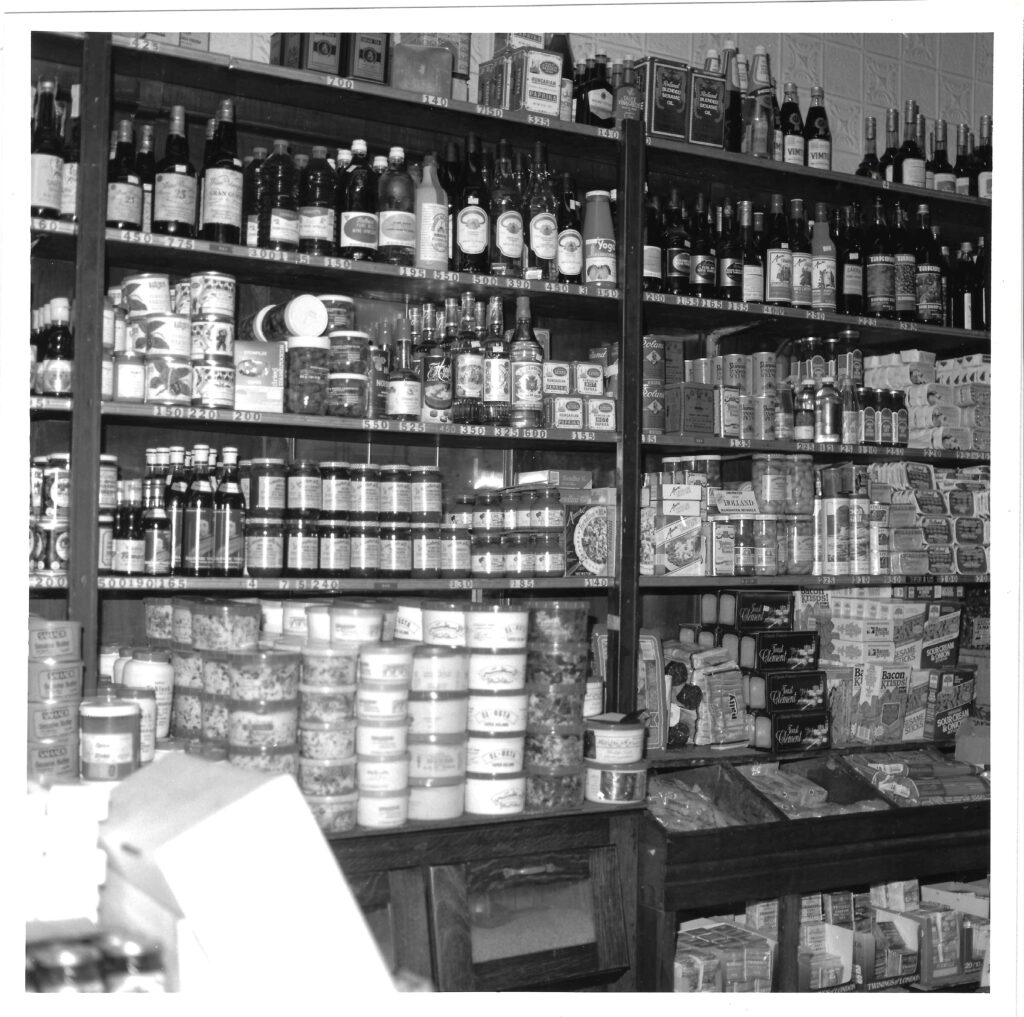

Images of Sahadi’s over the years (images courtesy Sahadi’s):

This podcast was partially based on this 2015 article written for this website:

Manhattan is profound for the layers of history that exist on even a modest spot of land. And in the case of blocks south of the World Trade Center, you don’t even have to go back far in time to find some surprising stories of the past.

One hundred years ago, strolling along the southern ends of Washington and Greenwich streets, you would have found yourself within New York’s first Middle Eastern community.

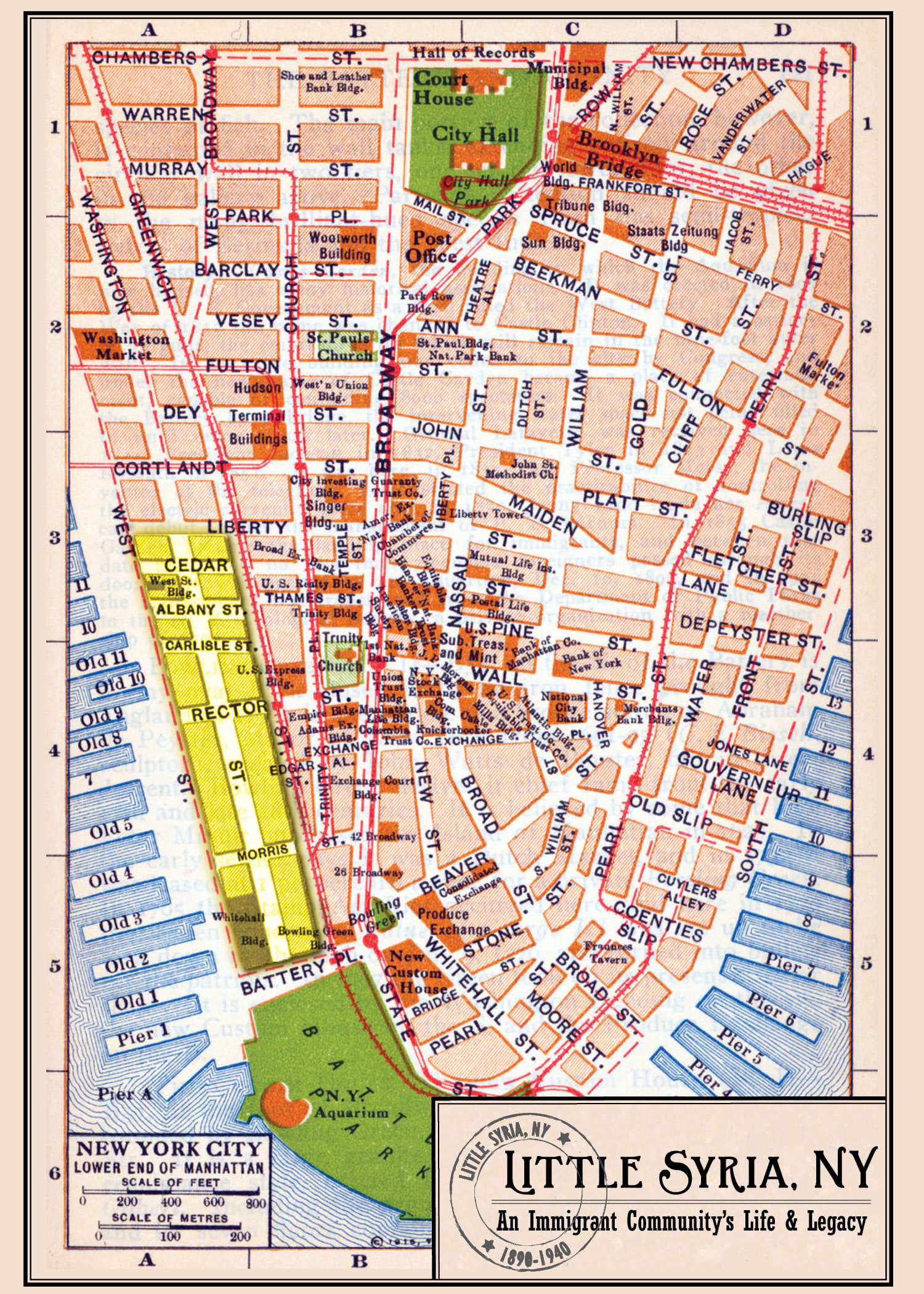

An approximation of the district in yellow (courtesy the Arab American Museum):

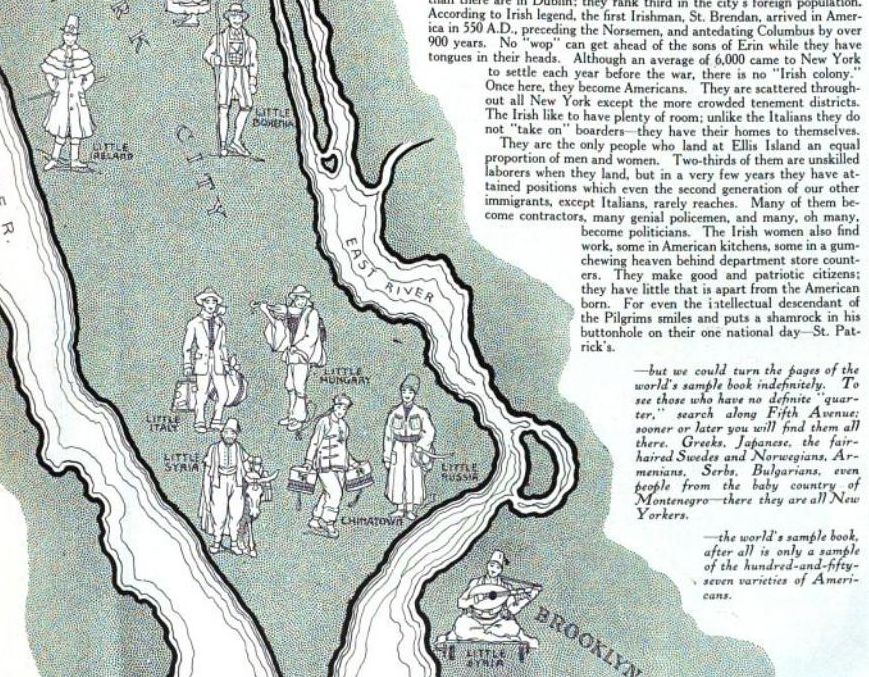

Little Syria (or the Syrian Quarter) featured rug and trinket shops and restaurants with “exotic” cuisine mentioned frequently by the newspapers of the day. In many ways it resembled the early days of Chinatown, a closed community, linked by language, rich in history and confounding to most New Yorkers.

Early New York Times writers were occasionally fascinated with this unusual pocket of settlement.

In 1898, they described it as quiet colony: “It differs much from other foreign quarters in New York. There is nothing forbidden in the aspect of the people or their places of business. The homes are clean and inviting and the stores where Turkish rugs, laces, perfumes, and tobacco are sold, display evidences of prosperity.”

While called ‘Little Syria’, it actually contained populations from several Middle Eastern communities. In the late 19th century, the idea of a ‘Greater Syria’ itself contained “modern Syria, Lebanon, Israel, Jordan, Palestinian Authority, Gaza Strip and parts of Turkey and Iraq.” [source]

As a Gilded Age New Yorker, if you knew Little Syria at all — and most New Yorkers stayed away from the ethnic ‘Little’ neighborhoods (Italy, Africa, Hungary) — it was because of the food.

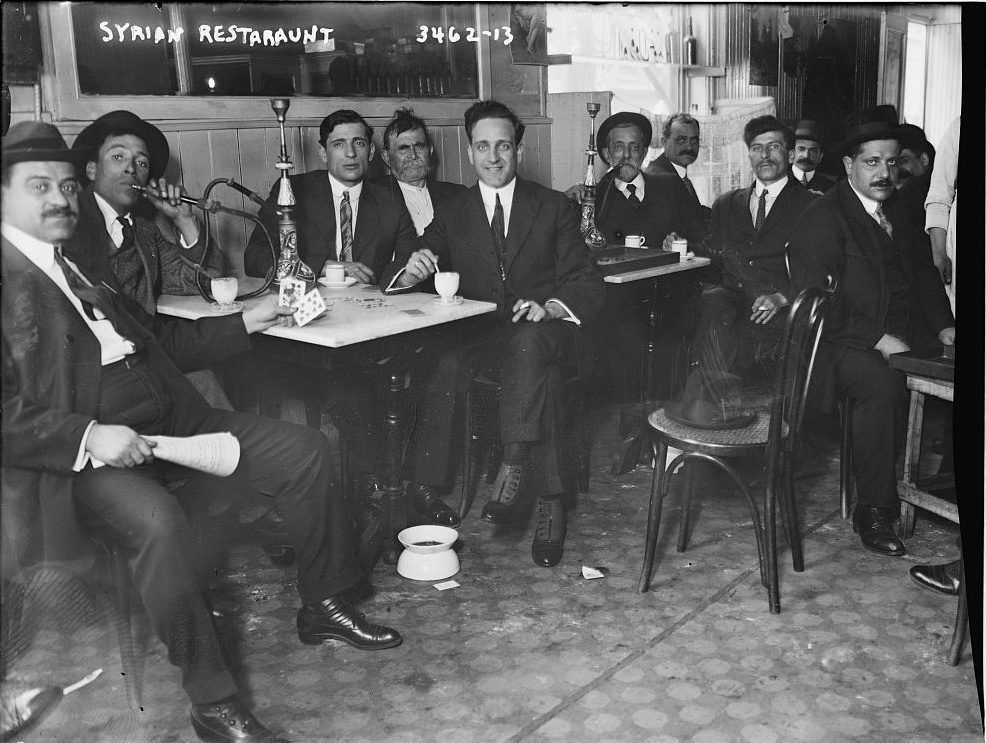

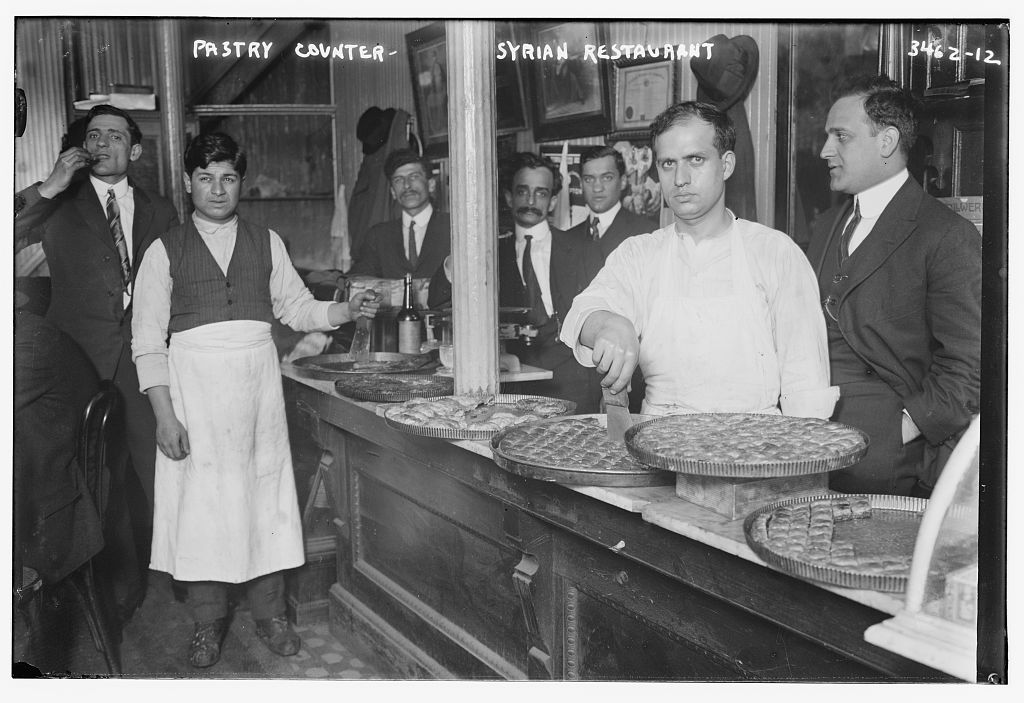

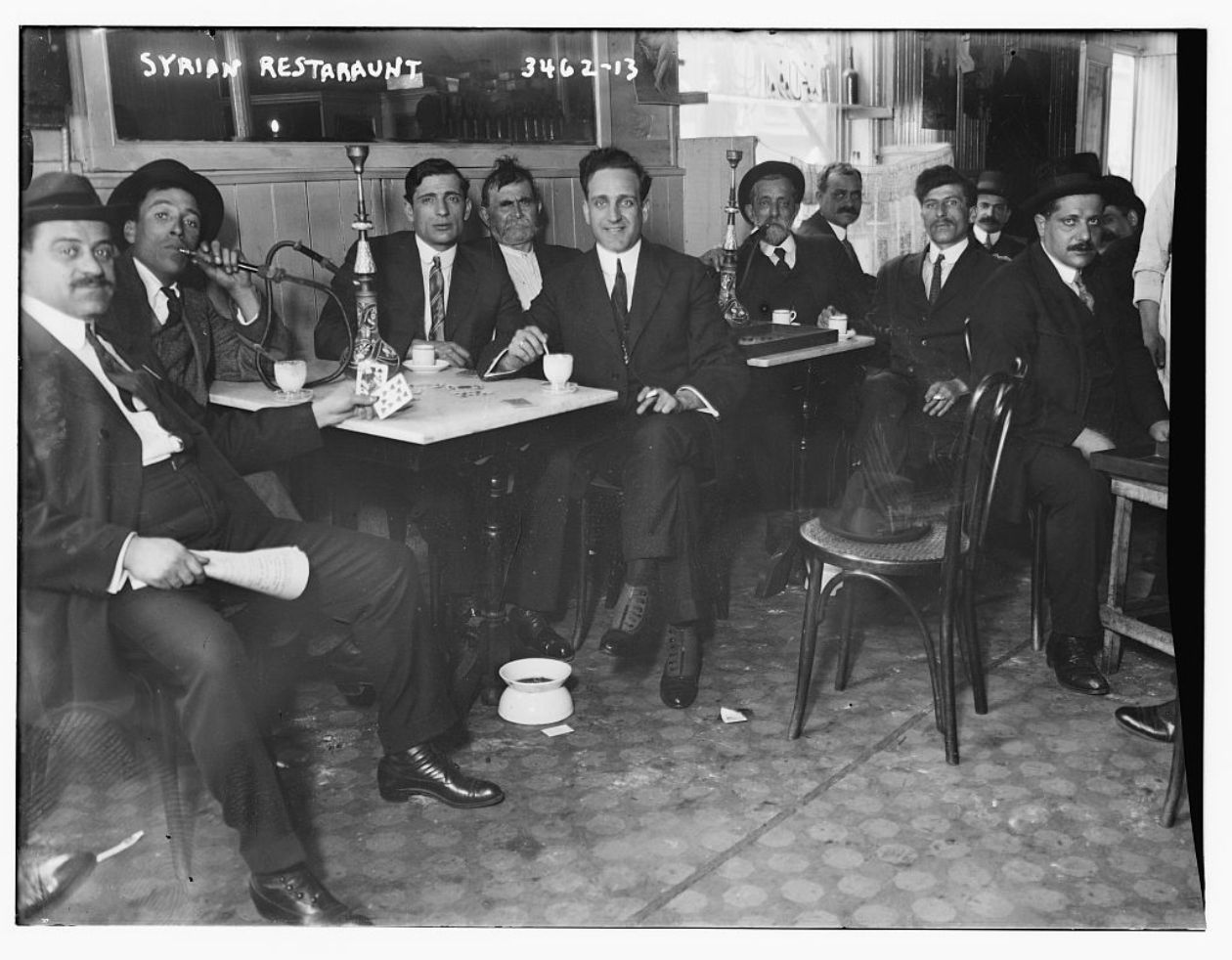

Another New York Times article from 1899 describes it with the passion of a modern restaurant critic: “It is in the restaurants that become cafes, after Syria has eaten her evening meal, that what is perhaps the most interesting life is to be seen.”

Of its inherent exoticness: “One glance at the Arabic bill of fare, written in Arabic script on a flimsy bit of white paper, shows the impossibility of making head or tail out of it.”

There were clearly few frames of references for those who visited this district. A 1903 New York Tribune describes the population of Little Syria as “fugitives from the Sultan’s tyranny” and describes the streets like something out of a chaotic wonderland:

“The shop windows are filled with huge Turkish pipes, whose water filled bulbs and serpentine stems would seem able to bring to the smoker all the dreams of the Thousand and One Nights. Here too the passerby may see lamps of Damascus brass, both great and small, and lighted by innumerable tiny tapers. They look much as the imagination might picture the lamp of Aladdin.”

People may have been prone to stereotype Syrian shops, but in fact the Syrian Quarter was known for a wide variety of goods including jewelry, lace, embroidery, rugs, cigarettes, coffee and so-called ‘kimonos’ then (actually kaftans).

Over a quarter of a million people of Middle Eastern descent were living in America by the early 1920s. Although from a great swath of locations, they were frequently just called ‘Turks’ or ‘Syrians’. (The Sultanate of Ottoman Empire was abolished in 1922 and its territories made independent. )

The first Middle Eastern immigrants to the United States were Christian Syrians and mostly young men, following a similar pattern of immigration as the Italians.

Women and children began coming over soon afterwards once their husbands or brothers established themselves, either as workers on construction crews or as private business owners.

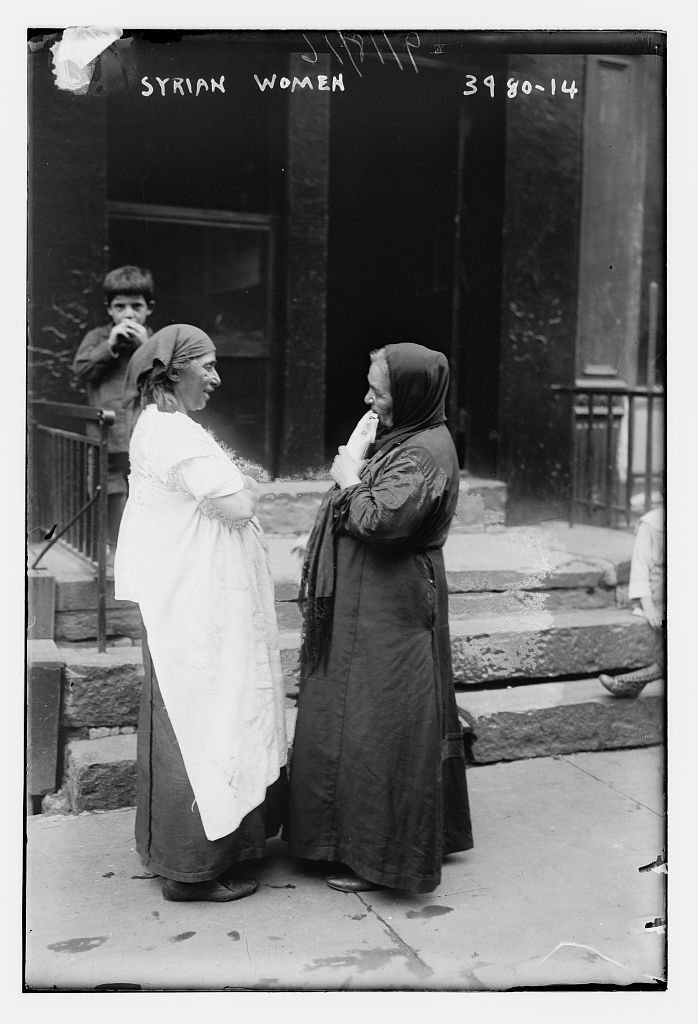

In 1903 the Tribune observed a line of “olive skinned women” diligently sewing on the street, employed as seamstresses in a scene being played out all over New York in other neighborhoods.

Many in the Syrian Quarter were silk and lace manufacturers back home, and some even commuted to work in Paterson, NJ, the so-called silk making capital in the United States at the turn of the century.

The pictures you see in this post were all taken sometimes between 1915 and 1916, a traumatic time in world affairs and the Middle East in particular.

Some were Armenians, cut off from regular news from back home and only sporadically aware of the horrors their families were experiencing.

The men who met up in Washington Street cafes smoked hookahs, drank coffee and played games of chess or checkers. Unlike the stereotypes presented in the press of ‘simple’ shop owners, many were well educated and spoke English.

While most of the earliest residents of the Syrian Quarter were actually Syrian Christians, by the 1910s both Christians and Muslims lived in the neighborhood.

The only vestige of Little Syria that remains today is the home of a former Catholic congregation — St. George’s Syrian Catholic Church at 103 Washington Street.

The congregation moved here in 1925, but by that time, a larger Middle Eastern community was developing in Brooklyn on Atlantic Avenue. Many vestiges of Brooklyn’s ‘Syrian quarter’ still exist today along Atlantic Avenue between Court Street and the waterfront, most notably Sahadi’s.

Below: An illustration from a 1918 Methodist journal called World Outlook, marking the ethnic enclaves of New York

Most of Manhattan’s original Middle Eastern neighborhood was eliminated with the construction of the Brooklyn-Battery Tunnel which opened in 1950 (although a long construction period cleared out the neighborhood by the early 1940s).

Those shops that managed to stay on shared the streets with a surprising new neighbor — radio.

Radio Row, considered Manhattan’s first technology sector, arrived just as terrestrial radio became the latest craze. Shops sold radio consoles, speakers and (after World War II) even ham-radio equipment, all centered at the corner of Cortlandt and Greenwich streets.

3 replies on “A Trip to Little Syria: A New York Immigrant Story”

We are a city of immigrants… another great post. Thanks!

I must revisit Little Syria on my next trip to NYC…It was at least 20 years since I walked within Little Syria.

I may add my next visit to my fourth book. Just completed my third book title: The Last American in Damascus…

Enjoy…

I just wanted to add I grew up in “Little Syria” in Brooklyn although my family’s background is Lebanese/Armenian. It was great. I was born in 1941 and remember fondly all the fun and foods from Sahadis and sweets from Alwans that we could get Arabic ice cream with or without pistachio nuts…the best. Mr Alwan went to his grave with his recipe. Going every Sunday after church to buy Syrian bread from the many stone oven bakeries and we would dig into the hot bread on the eat home. all the folks knew each other and it was a good place to grow up.