The Metropolitan Museum of Art contains a very unusual piece of art tied to the early history of City Hall. In fact, this piece is responsible for what is sometimes considered New York’s very first art museum — decades older than the Met itself.

The strange oil painting is called Panoramic View of the Palace and Gardens of Versailles by John Vanderlyn (pictured below). Strange, because it’s a circular work of art, requiring its own room in the American wing of the Met, where it is broken into two pieces that immerse the viewer who walks between them.

Vanderlyn was a painter of great renown at the start of the 19th century, despite being a protege and close friend of disgraced vice president Aaron Burr. He went on to create portraits of many great men of the age, including several presidents.

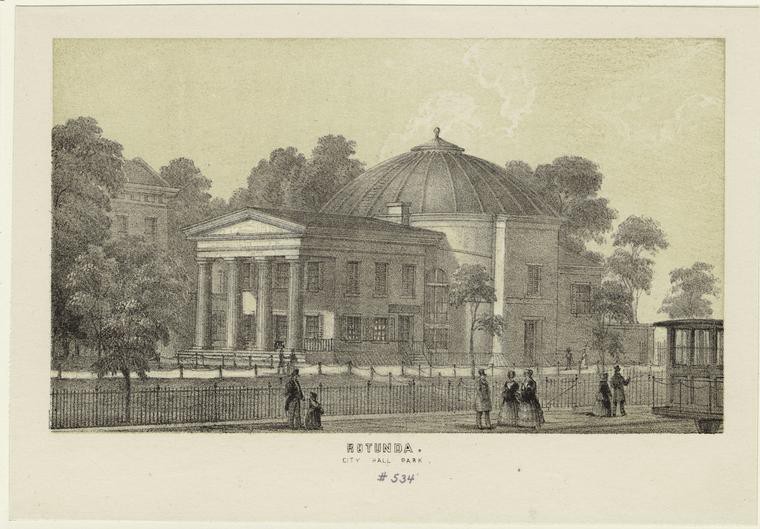

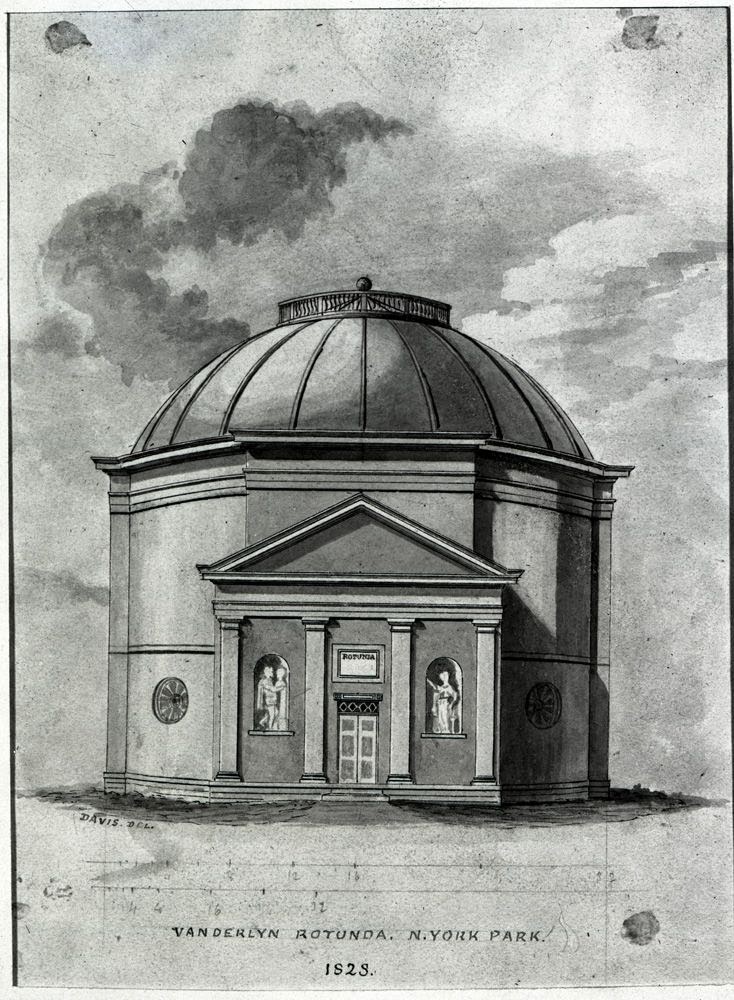

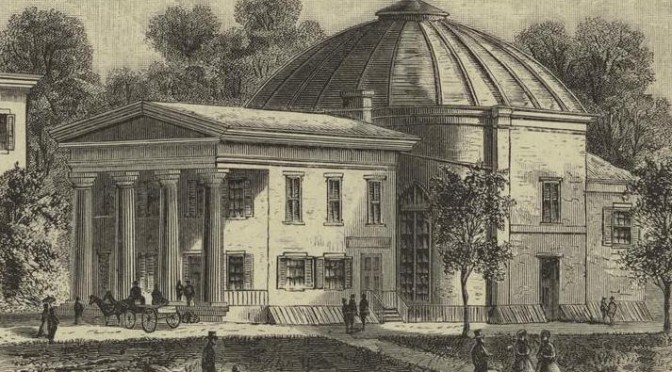

The artist painted the Versailles panorama in 1818 in his childhood home of Kingston, New York, about a 100 miles north of the city. With the support of some wealthy New York patrons (including John Jacob Astor), Vanderlyn received permission from the city to build a small rotunda in which to properly display this odd, grandiose canvas. And prime real estate it was, located just a few steps north of the newly built City Hall at Chambers Street and Cross Street (or, today’s Centre Street).

The artist painted the Versailles panorama in 1818 in his childhood home of Kingston, New York, about a 100 miles north of the city. With the support of some wealthy New York patrons (including John Jacob Astor), Vanderlyn received permission from the city to build a small rotunda in which to properly display this odd, grandiose canvas. And prime real estate it was, located just a few steps north of the newly built City Hall at Chambers Street and Cross Street (or, today’s Centre Street).

It was also next door to an abandoned almshouse; the residents of this facility had been shipped off to the newly created Bellevue Hospital by this time and the building’s hallways were filled with loftier organizations, like the New-York Historical Society and Scudder’s American Museum. Classy, and perfect for a neighboring vanity museum.

Vanderlyn’s self-designed gallery* was tiny but intense, a miniature Pantheon with domed roof 40 feet overhead. Uniquely, it was an art museum designed to focus on one artist — Vanderlyn. However, the piece was not completed in time for the Rotunda opening, and another panorama was displayed — a presentation of the city of Paris by Robert Barker, an Irish artist who allegedly invented the panoramic painting.

Eventually Vanderlyn brought Versailles to the Rotunda on May 26, 1820, as well other panoramas of Athens and Geneva, enhanced of course by the presence of more traditional paintings. The stipulation was that the artist could use the space as his own personal showroom for nine years, when it would pass over to the city for their own purposes.

Below: a segment of Vanderlyn’s panorama, courtesy the Met

However, it appears he grossly overestimated his own appeal. Vanderlyn was constantly owing money for the building’s upkeep and audiences never flocked to the gallery in numbers that would make it profitable. The artist would have to take some pieces on the road to boost interest in them.

Well before his nine years were up, Vanderlyn was interested in renewing his lease, but New York City had other plans. Despite the pleas of some of Vanderlyn’s wealthy friends, the building was refitted as a small courthouse — for a Court of Sessions (county-run criminal court) in 1829 — and morphed, for a time, into New York’s naturalization office and a neighborhood post office.

Art returned briefly to the Rotunda in 1845 when it was used in the inaugural display from the New York Gallery of the Fine Arts, a consortium of art collectors who pooled together a stagger rent of “$1 a year” to shhow off their collections of European paintings. The Gallery only stayed at the Rotunda for a short time, moving to a more elegant gallery at 663 Broadway in 1848 and dissolving entirely when they donated their entire collection to the Historical Society ten years later.

By then, the classic glory of the Rotunda had been muddied by additions mandated by the city to turn the domed structure into government offices. Where once the glories of Greece and France once hung, New York plopped down its water board and home of the Almshouse Commissioner. Despite an attempt at appropriate alternations — including a “propylaeum, having a portico and four Doric columns” — the Rotunda never again returned to any sort of aesthetic glory. It was ripped down entirely in 1870, in time for the city to start construction of the Tweed Courthouse.

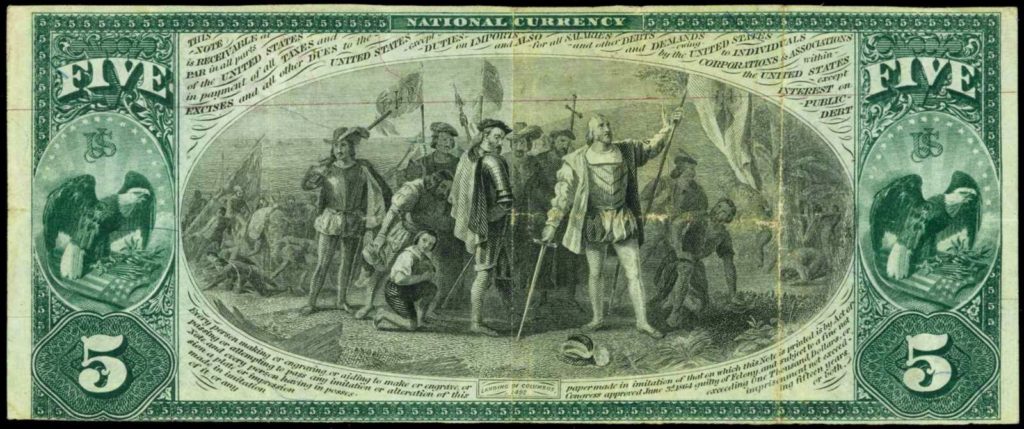

As for Vanderlyn, true success continued to evade him. In 1842, he would paint one of his most well-known pieces, The Landing of Columbus, a commission from the U.S. government that was used on the five-dollar bill. Yet, just ten years later, Vanderlyn would alledged die in poverty back in his home in Kingston, where he had created the Rotunda panoramas.

Below: Vanderlyn’s painting and the money it appeared on

His Versailles painting would receive a grand reception when it was donated to the Met in 1956. The museum built a special circular room just contain it.

Click here for a nice review of Vanderlyn’s Versailles panorama and an overview of the entire panoramic phase of painting.

* Many sources seem to grant Vanderlyn the honor of designing the Rotunda himself, although one source lists a more-likely candidate — Martin Euclid Thompson, who was actually an architect.

(This piece originally ran on this blog in 2009)

2 replies on “New York’s First Art Museum: The City Hall Rotunda”

[…] scene of the palace and gardens of Versailles, and to exhibit the 360-degree work inside a rotunda of his own construction, in the hope of securing his reputation and fortune. But Americans had little interest in […]

[…] panoramas require a circular space to correctly display the 360° view, Vanderlyn designed a rotunda near New York’s City Hall. This odd gallery was intended for one artist only: […]