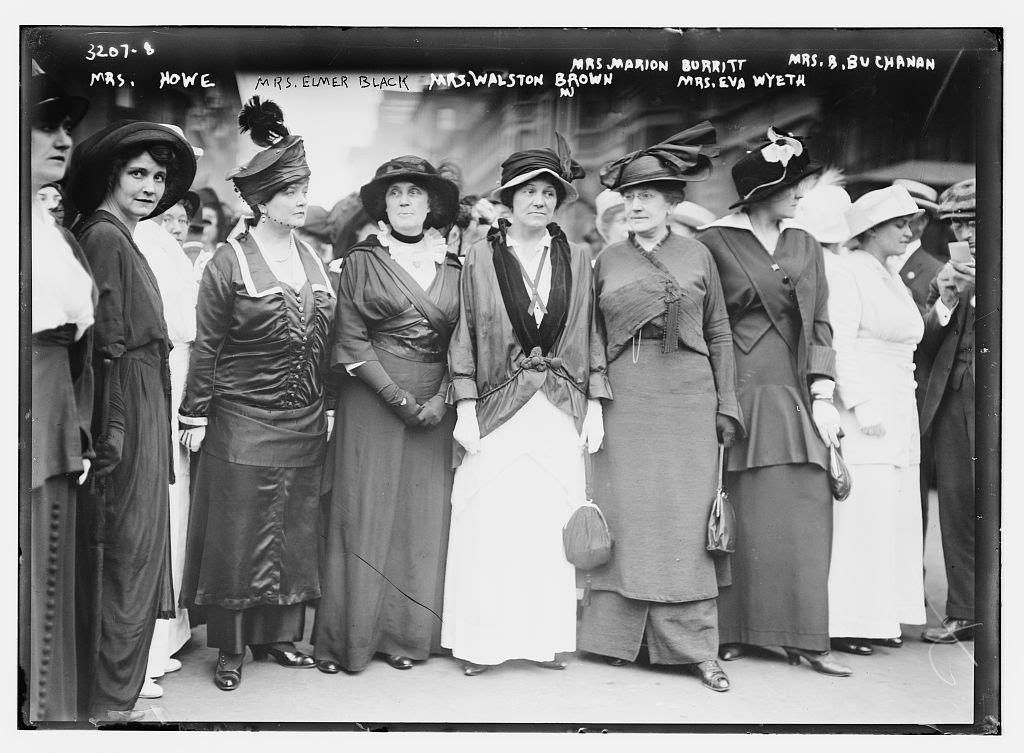

Below are some pictures of what’s possibly New York City’s first anti-war protest organized by women, on August 29, 1914.

War had erupted that summer in Europe, sparked by the assassination of Archduke Franz Ferdinand in late June and unfurling into a continent-wide catastrophe, as countries entered the fray on either side of the conflict. Within weeks of the conflict, New Yorkers with strong ties to individual nations were raising money and even boarding ships to fight alongside their distant countrymen.

In other cities with sizable European populations — such as Montreal — people were already marching, calling for an end to the conflict. And leading this call were women already involved in social organizations, in particular, suffragists with networks that reached into high society.

Protesting war has been a touchy issue in New York City. [See the Civil War Draft Riots for such a protest gone wrong.] The mayor had expressly forbade parades in support of individual nations on New York streets lest a microscopic version of the European conflict erupt here. Anti-war was often associated with socialist organizations and indeed, that August, several did march in Union Square. But these were comprised largely of men.

Which makes the Women’s Peace Parade so unusual. Prominent women met at the Hotel McAlpin in mid-August to plan what was essentially a mourning parade, with its participants — from all walks of life — dressed in black as though in a funeral procession. (As you can see in the pictures, many women also chose to wear white in a symbol of peacetime, garnished with black accessories.)

Many people didn’t quite understand what a peace protest even meant, seeing it as a wasted effort. One letter writer to the New York Times asked. “Will any of the women who intend to parade in protest of the war explain what they mean to accomplish by such a demonstration?”

While the parade drew from prominent individuals in the suffrage movement, others were simply not convinced. Carrie Chapman Catt, one of America’s most famous suffragists, remarked, “If anybody thinks that a thousand, or a million, women marching through New York or talking about peace in the abstract will have any effect on the situation in Europe, it is because they don’t know the situation in Europe.”

But, in fact, there was a motivation. One of New York’s leading activists Harriet Stanton Blanch — daughter of Elizabeth Cady Stanton — was very succinct about their motivation. “This is a movement for actual work. We intend to do something definite. We wish to have a meeting at The Hague Peace Conference called.”

The parade began in the afternoon, marching down Fifth Avenue from 58th Street down to Union Square. Women who either lived or shopped along the avenue now marched in formal procession down it, accompanied by the “ominous beat of muffled drums.” There was occasional applause but otherwise “the general silence of the great gathering was considered the best evidence of understanding.” [source]

The parade marshal was the young Portia Willis, a magnetic lecturer on the suffragist circuit. .

While the organizers announced there was to be only one flag on display in the parade — the flag for peace — one other crept into the proceedings. “The smallest Boy Scout was Alfred Greenwald, 4 years old, who … attracted much attention. Little Alfred unknowingly broke the most stringent rule of the parade by carrying a flag. He carried a United States flag but it was furled.” [source]

Unfortunately I was not able to locate any pictures of the second half of the parade — with 250 African-American women in solidarity, followed by “a number of Indian and Chinese women” and carloads of elderly women and babies.

Those who witnessed the parade would not soon forget it, especially in the following months as the conflict that would become known as World War I grew to eventually encompass the United States.