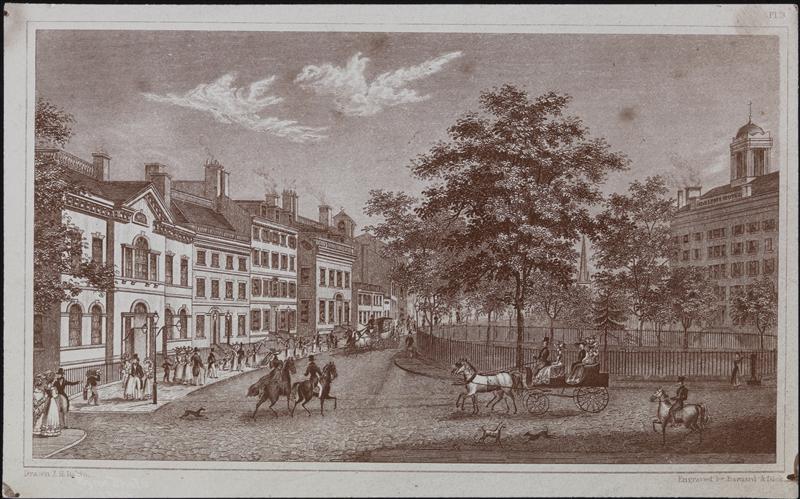

Here is New York — not the evened tree-lined avenues with fashionable ladies and shiny new carriages.  Not an ordered town of impressive architecture and manicured parks, emulating and even surpassing the trappings of European society.  Those things would arrive by the 1880s; before then, they were mostly aspirational designs.

Here is New York as it actually was. Â Dogs and pigs — hundreds of them — wading through muddy streets of detritus, neighborhoods reeking of human filth and boiling offal. Â Blocks dominated by poorly constructed buildings, spilling waste into the streets. Â Foul and unhealthy conditions for daily living, fostering sickness and disease. Watch out for that dead horse in the street.

That, of course, may be as exaggerated as the first example, but you come out of reading Taming Manhattan: Environmental Battles In The Antebellum City (Harvard University Press), the terrific new urban history by Catherine McNeur, with that impression. You’ll certainly need a bath afterwards.

McNeur, a professor at Portland State University, isn’t immediately concerned with the taming of the natural land — that is, the transformation of the island into an urban area, although the great hallmarks of that achievement (the Commissioners Plan of 1811, the draining of Collect Pond) are mentioned here.

Instead, Taming Manhattan focuses on the idea of turning ragged New Yorkers into modern urban dwellers. Â

Instead, Taming Manhattan focuses on the idea of turning ragged New Yorkers into modern urban dwellers. Â

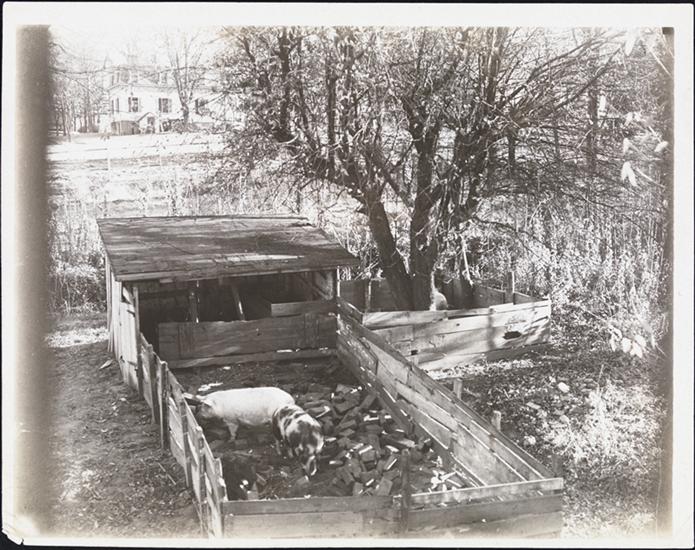

You could no longer, say, have your pigs run rampant through the streets. In McNeur’s survey of the 1820s-1850s, hogs become a significant problem.  They were an unsightly nuisance, attacking women and children and rummaging through garbage.

So too were wild dogs. Large packs of them roamed the streets, often violent and afflicted with rabies.  A 1811 dog law authorized the wholesale slaughter of any dog deemed in any manner dangerous.

One editor wrote, “[N]o dog out to be allowed to exist. Â The life of one single person is worth more than the lives of all the dogs in the United States; and while there is one dog living, there is danger that one or more persons may suffer the most cruel of all deaths in the course of a year.”

Even dead animals posed a threat as city custodians, few as they were, refused to pick up carcasses. Offal and bone-boiling companies, often with corrupt ties to city government, sprang up to tackle the problem. Â One notable company owned by William B. Reynolds turned Barren Island in Jamaica Bay into an offal oasis.

And it was a sick cycle of life here as well. Â As McNeur notes,” [f]ollowing the model of Manhattan offal boilers, Reynolds brought somewhere between 2,000 and 3,000 hogs to the island to fatten them with the city’s offal.”

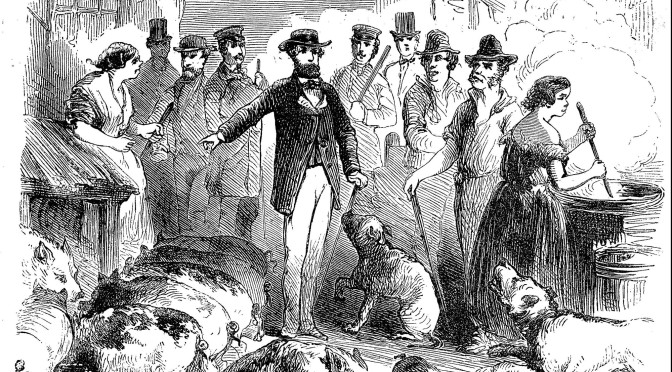

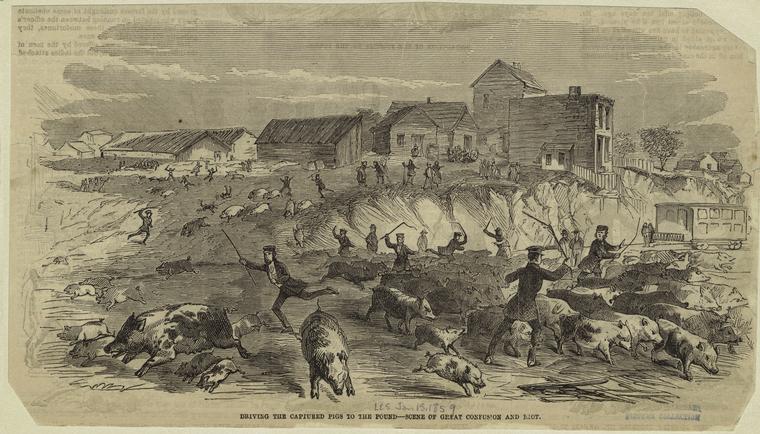

There were even the so-called Piggery Wars of 1859, when police officers raided piggeries — pig farms where pork was produced for market — in an area called ‘Hogtown’ in the area of the 50s between Sixth and Seventh Avenues.  As you read McNeur’s vivid recounting of this purge — “they came armed with guns, clubs, pickaxes, crowbars, and a team of reporters” — remember that it is all taking place around the area of today’s Broadway district.

Waste products left by horses and other animals became highly valued as fertilizer for farmers. In fact, a couple intrepid companies attempted to sell off human waste (“night soil”) in the same manner, to lesser success.

Of course, there was a class and racial component to this sudden ‘taming’.  New York’s new wealthy classes, enriched by the opening of the Erie Canal, wanted clean promenades and handsome private parks in which to luxuriate.  And it wanted additional lands to expand, meaning the shantytowns were swept away with the rendering plants.

We benefit from New York’s eventual modernization, but there is an undercurrent in Taming Manhattan of a wholesale cleansing that is not entirely altruistic.

Watching the many changing motivations unspool in McNeur’s dense but exciting narrative makes for a surprisingly unpredictable tale. For instance, dogs and hogs may be among the principal offenders two hundred years ago. But take a look around. There are no hogs in the street anymore, no heaps of horse dung, but New Yorkers greatly value their four-legged canine friends far more than before.

But watch your step.