BOOK REVIEW The architects and builders of the post-Civil War period provided New York City with masterpieces of great beauty — cast-iron facades, modern emblems of trade rendered in marvelous stone, fanciful medieval gargoyles upon impressive towers. Gilded Age architecture and the ornate shapes of pre-modern design have nonetheless defined the timeless identity of the city.

In the 1970s lovers of this fading architectural landscape decided to protect its most treasured features. By liberating its details from the landscape entirely.

They were called ‘gargoyle hunters’, so passionate for the city’s magnificent beauty that they would rather steal aspects of it than see it destroyed.

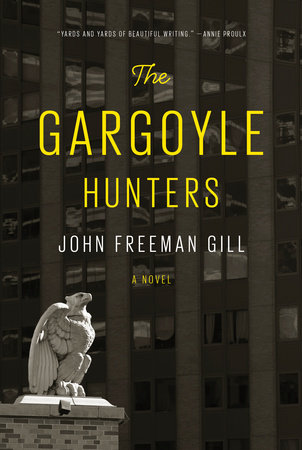

The Gargoyle Hunters

by John Freeman Gill

Alfred A. Knopf

John Freeman Gill‘s new book The Gargoyle Hunters is obviously about one of these guerrilla collectors, working with a crew of thieves, chipping away at doomed architectural wonders falling into disrepair, scouring heaps of rubble for a bit of beauty in a city tumbling into financial ruin.

One of the thieves is the gargoyle hunter’s son. His name is Griffin.

Shortly into Gill’s captivating and exuberant novel, one realizes that architectural crimes are merely the backdrop. This is a story about all varieties of nostalgia. Formalized urban nostalgia, of course, of the kind that drives landmark preservation and podcasts about New York City history. But also the constant pining for recognizable moments in a person’s life, both for the pleasures of our childhood and for the relationships that once held us in safety.

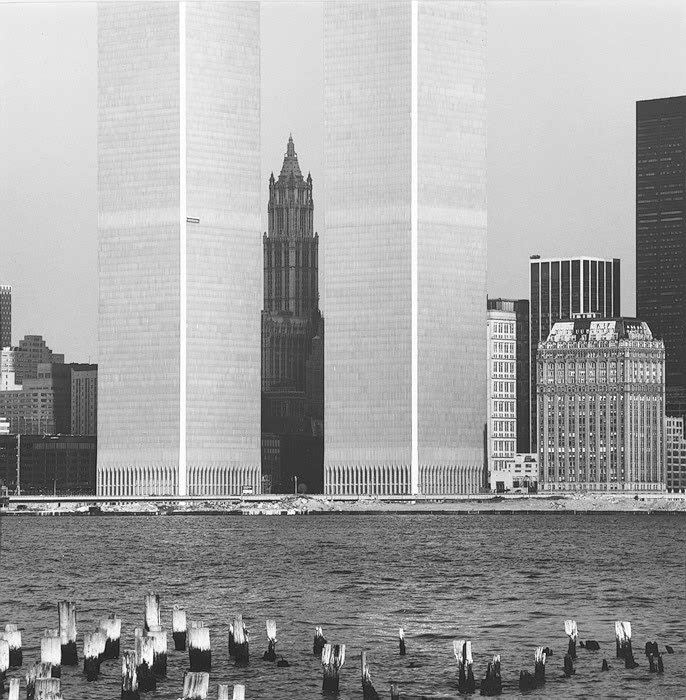

Below: The World Trade Center, with the Woolworth Building peering through — two architectural contrasts in Gill’s novel (photo date 1973)

Gill, a New York-based journalist and New York Times contributor, is the son of a ‘gargoyle hunter’ who traipsed 1970s in search of aged, deteriorating treasures, and his adventure, while certainly fictionalized, has the immediacy of a memoir, laced with specific references to corner shops, restaurants and cheap snack foods.

Griffin’s parents are separated so he spends time between his home – a rustic, unrenovated brownstone on the Upper East Side — and his father’s workshop in a warehouse in Tribeca, many years before chic hotels and film festivals would arrive here. Griffin has accepted the separation, if mournfully, just as he assumes New York as a faded, withering place, the rubble upon which the foibles of his adolescence play out.

Below: Heaps of rubble abound in early 1970s New York. In The Gargoyle Hunter, they sometimes possess abandoned treasures.Â

But those around him are not so complacent. His sister spends her time trying to piece her family back together in crafty ways. At one point, she smashes a window with a rock, knowing her father will have to come back and repair it.

Her father also vandalizes to repair the past, soon employing his son in wild and increasingly dangerous capers to remove carved detailing from old Gilded Age buildings, finding great spiritual urgency in his tasks.

“The bridge of time is very poignant,” he told me. “I think about the immigrant carvers who came over here and did this work on people’s home — itinerant nobodies, many of them, with no stable homes of their own — and I meet them across time.”

Their adventures soon lead to a startling heist — the theft of an entire building.

“No, not part of a building, son. What we’re going to steal is a building — the whole damn thing, cornice to curb. Just stop asking so many questions and you’ll see. Okay?

(NOTE: This sounds far-fetched, but Gill bases this on an actual event of a cast-iron structure win 1974.)

Below: The ramshackle streets of Tribeca, another vivid location from the book

I feel as though Gill is doing a bit of gargoyle hunting from his own life, the novel filled with charming and very specific anecdotes of teenage exuberance and wistful remembrance, dotted along the corridors of 1970s New York that you can almost follow along with on a dusty map.

There’s even a marvelously awkward experience atop the Statue of Liberty, one that feels gleefully unrestricted, with a major nod to modern cinema’s greatest ode to nostalgia — A Christmas Story.

The central crimes (or are they rescues?) of The Gargoyle Hunters feel realistic because they’re paired with the common trials and errors of teenage life, moments we all wish we could chip away and save forever.