“The nomination of Arthur is a ridiculous burlesque …. He never held an office except the one he was removed from. His nomination attached to the ticket all the odium of machine politics and will greatly endanger the success of [James] Garfield. I cannot but wonder why a convention, even in the heat and hurry of closing scenes, could make such a blunder.”

— John Sherman

A monument to Chester A. Arthur stands in the northeast corner of Madison Square, solitary and deadened, an homage to a president standing in a park named for a better president.

Arthur was not a great man, nor was he as terrible as his legacy suggests either. His primary skill was loyalty, a reliable foot soldier who achieved an impressive career almost by accident. And yet the biographies of such men can make for excellent reading, not because of their character but because of their circumstance.

The Unexpected President

The Life and Times of Chester A. Arthur

by Scott S. Greenberger

Da Capo Press

In The Unexpected President, Scott S. Greenberger’s excellent page-turning biography on Arthur, the Vermont attorney-turned-New York social climber is respectfully drawn, but the author never makes excuses for his subject’s lack of charisma. In fact, his mild charms would become an asset.

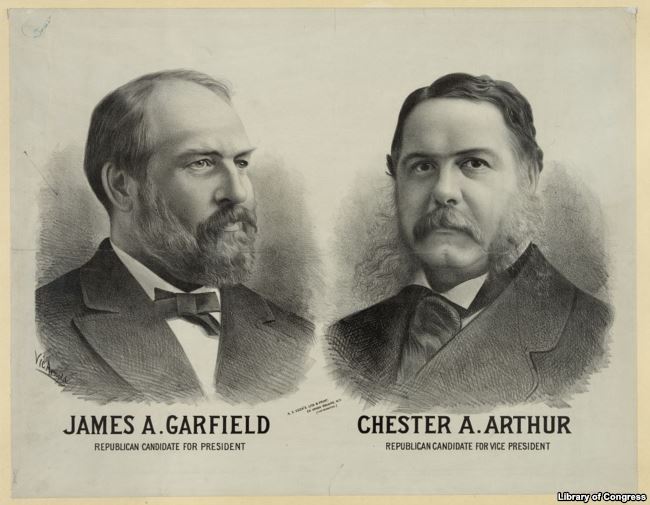

To become the 21st President of the United States, Arthur piggybacked upon the ambitions of more calculating men — Republican Party founder Thurlow Weed and, most famously, Republican boss Roscoe Conkling. To make a somewhat vulgar modern analogy, he’s like that reality show contestant who wins the competition by not making any real moves at all. He’s one of our nation’s great Under The Radar Americans.

The most fruitful job Arthur ever held was as collector at the New York Custom House, an appointed position that offered hundreds of free jobs to political climbers. Â Although he would be removed from the position in 1878 after a highly publicized corruption investigation, Arthur’s reputation remained strangely unblemished. Indeed, he threw himself into promoting Republican candidates in an era where Democrats (fueled by Tammany Hall) were often seen as most politically ruthless.

The New York Times noted at “[Arthur’s] name very seldom rises to the surface of metropolitan life and yet moving like a mighty undercurrent this man during the last 10 years has done more to mold the course of the Republican Party in this state than any other one man in the country.”

Greenberger’s book is filled with zesty jabs between politicians and corrupt machinations of the spoils system that were once so prevalent (and are, perhaps, prevalent again). In the most entertaining sections, Arthur is often off to the side, whether it be dutifully wrangling votes or dollars in dramatic presidential elections or watching his boss Conkling practice political suicide by resigning from office.

He became James A. Garfield‘s vice president almost by accident and later became president by tragedy (Garfield’s assassination in 1881). He was sworn in as the 21st President of the United States on September 20, 1881, at 2:15 a.m, from the green-shuttered parlor of his home at 123 Lexington Avenue (at right), one of many wonderfully drawn New York City locations described in Greenberger’s book.

He became James A. Garfield‘s vice president almost by accident and later became president by tragedy (Garfield’s assassination in 1881). He was sworn in as the 21st President of the United States on September 20, 1881, at 2:15 a.m, from the green-shuttered parlor of his home at 123 Lexington Avenue (at right), one of many wonderfully drawn New York City locations described in Greenberger’s book.

Another of these locations is, of course Delmonico’s Restaurant, the premier destination for America’s cigar-chewing industrialists and power brokers, where the drunken Vice President Elect rose to give a speech “that reinforced the widely held view that he was a machine politician unfit for high office.”

And yet this minor president did manage something rather unexpected once in office, taking up a cause few would have assumed he was interested in at all — civil service reform. Under pressure, this tool of machine politics would begin to demonstrate his own style of leadership.