There were five, maybe six moments, during the reading of Begin Again: James Baldwin’s America and Its Urgent Lessons For Our Own where I experienced something that few books had ever made me feel — that the pages were being written as I turned them.

The sentiments so immediate and revealing of this moment — as in, right now — that certainly, the author Eddie S. Glaude Jr. must be sitting somewhere, cranking out new sentences which flew through the ether and landed between the covers on a future page, just a few ahead of my dog-eared fold.

And to experience this immediacy in a history book — or at least a book that remixes history with poignancy, pairing past incidents with present — grants the whole reason we study history in the first place a whole new stature.

But that of course is the enduring power of James Baldwin.

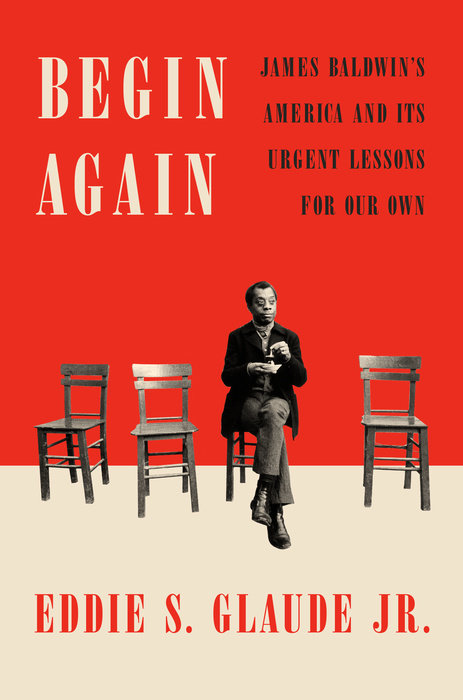

BEGIN AGAIN

James Baldwin’s America and Its Urgent Lessons For Our Own

by Eddie S. Glaude Jr.

Crown Publishing

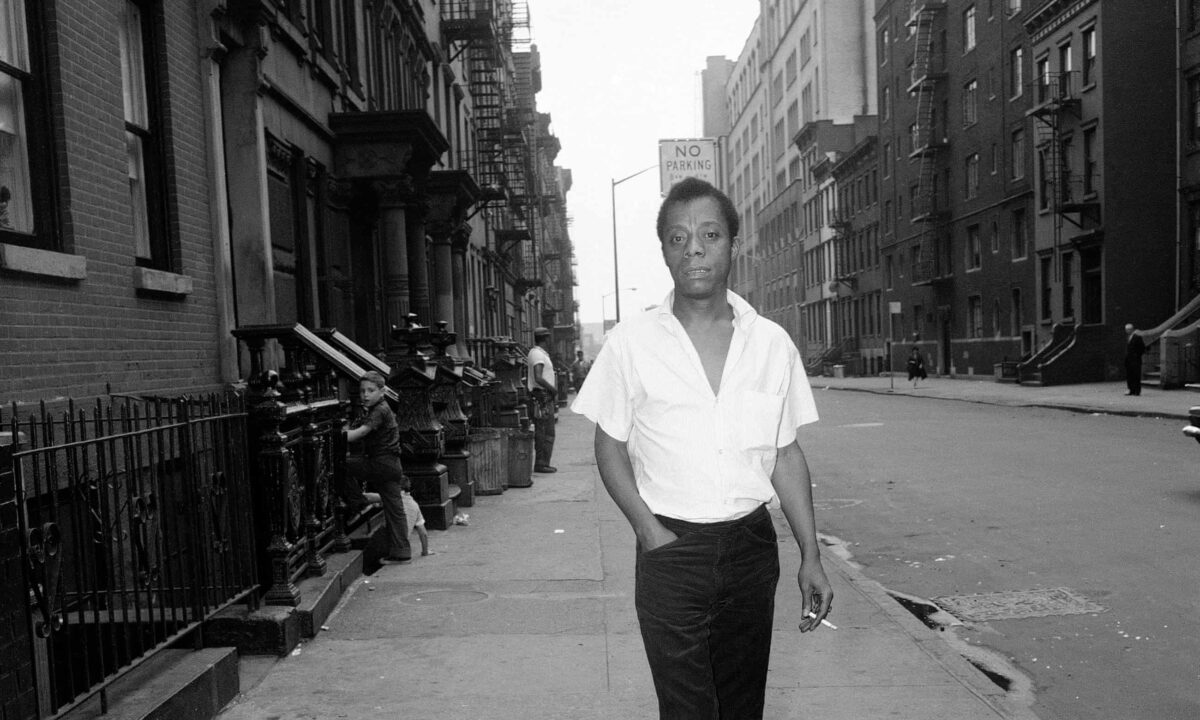

We go to Baldwin again and again not because the man’s identity as a queer black writer feels like a relevant voice for a diverse world. Baldwin speaks to our modern world because he is in, but not always a part of, the past.

In Begin Again, Glaude, the James S. McDonnell Distinguished University Professor of African American Studies at Princeton University, has invited Baldwin to analyze our world.

“As a critic of the after times, Baldwin is like a blues singer who sings about a crossroads,” writes Glaude. “He stands at a railroad junction, where he can go in multiple directions. He is betwixt and between possibilities.”

Those possibilities, meaning America’s decisions on racism and equality. And if 2020 hasn’t given you a clue yet, America rarely chooses the better road.

In Begin Again, Glaude presents a selection of moments from Baldwin’s life and his writings from those moments, then a modern perspective of those views.

Glaude and Baldwin are most often in a duet with one another, letting Baldwin’s past words underscore or sometimes even directly address a present situation.

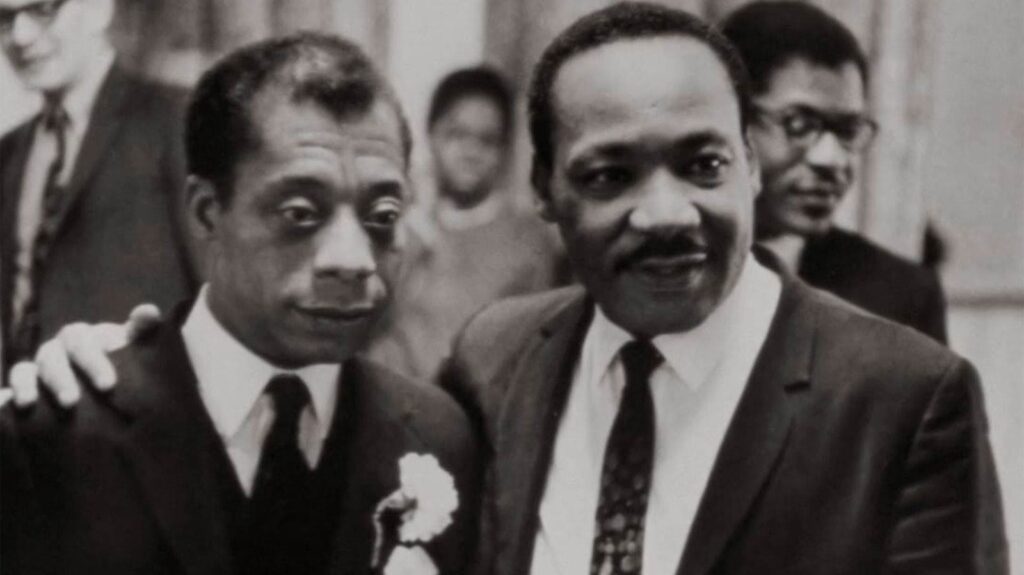

The “after times” that Glaude refers to — a term taken from Walt Whitman, one of many 19th century writers drawn into Baldwin’s story — refers to, as he writes, “the collapse of the civil rights movement, bearing witness to a time when many thought the nation was poised to change, only to have darkness descend and change arrested.”

The death of Martin Luther King Jr. and Malcolm X. The hope of non-violent protest replaced with the armed, more aggressive rhetoric of Huey Newton and Stokely Carmichael. The promise of government action, abruptly halted with the election of Richard Nixon.

Baldwin spent his life writing about what Glaude calls the lie, really a set of cultural choices that continually prefer and prop up white America above all else, so enshrined in system and form that to undo it would seem, for those benefiting from them, like anarchy.

Baldwin writes:

“What is most terrible is that American white men are not prepared to believe my version of the story, to believe that it happened. In order to avoid believing that, they have set up in themselves a fantastic system of evasions, denials, and justifications, [a system that] is about to destroy their grasp of reality, which is another way of saying their moral sense.”

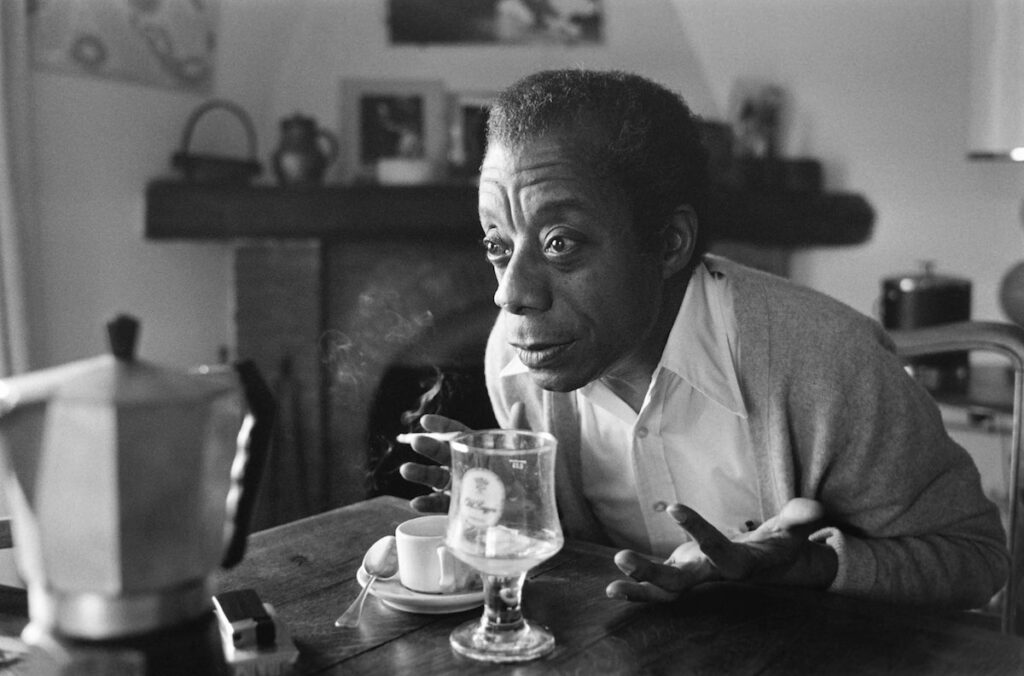

Glaude observes Baldwin as he reacts to images of Dorothy Counts, the African-American teenager harassed by racists in North Carolina as she entered high school. His reactions are not unlike ours today.

“Don Sturkey’s images of Dorothy Counts find their inheritors in pictures and videos we see today of the suffering of black people at the hands of police forces,” writes Glaude.

The author directs Baldwins’ words and stories directly at today’s headlines — at the racists in Charlottesville, at the dismantling of false histories enshrined in statues to the Confederacy, at the calculated hate rhetoric of the president.

The writer has much to say about racism as the defining corruption of American principles.

“In July of 1968,” writes Glaude, “just a few months after King’s assassination and against the backdrop of American cities burning, Baldwin gave an interview to Esquire magazine.

Q: How can we get the black people to cool it?

A: It is not for us to cool it.

Q: But aren’t you the ones who are getting hurt the most?

A: No, we are only the ones who are dying fastest.”

In a book practicing such an innovative dismantling of genre, it’s a wonderful surprise to find one chapter that is essentially a travelogue, following along with Glaude as he heads to Alabama, visiting the Legacy Museum: From Enslavement to Mass Incarceration and the National Memorial for Peace and Justice, a memorial to the thousands who have died from lynching.

And a memorial which opened in 2018 during the Trump administration.

From a 1979 piece by Baldwin, written, as Glaude notes, “on the eve of the election of Ronald Reagan”:

“Let us say that we all live through more than we can say or see. A life, in retrospect, can seem like the torrent of water opening or closing over one’s head and, in retrospect, is blurred, swift, kaleidoscopic like that.

One does not wish to remember — one is perhaps not able to remember — the holding of one’s breath under water, the middle of rising up far enough to breathe, and then, the going under again…..”