PODCAST In New York City, during the tumultuous summer of 1776, the King of England lost his head.

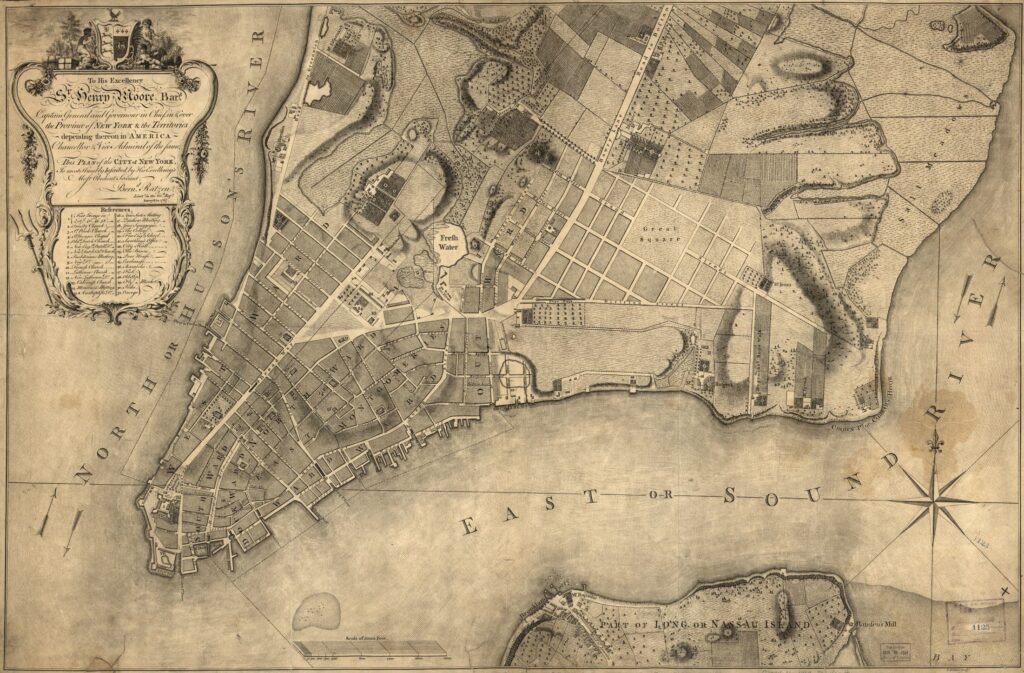

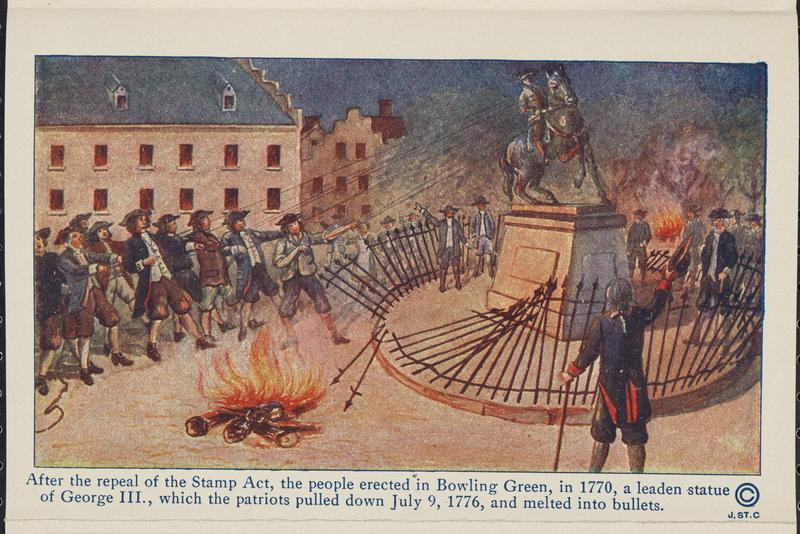

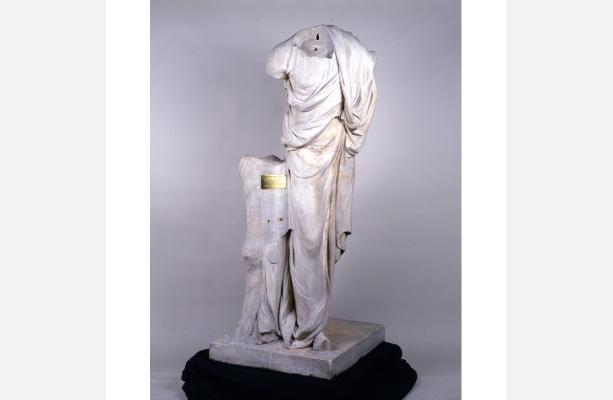

EPISODE 333 Two hundred and fifty years ago, Colonial New York received a monumental statue of King George III on horseback, an ostentatious and rather awkward display which once sat in Bowling Green park at the tip of Manhattan.

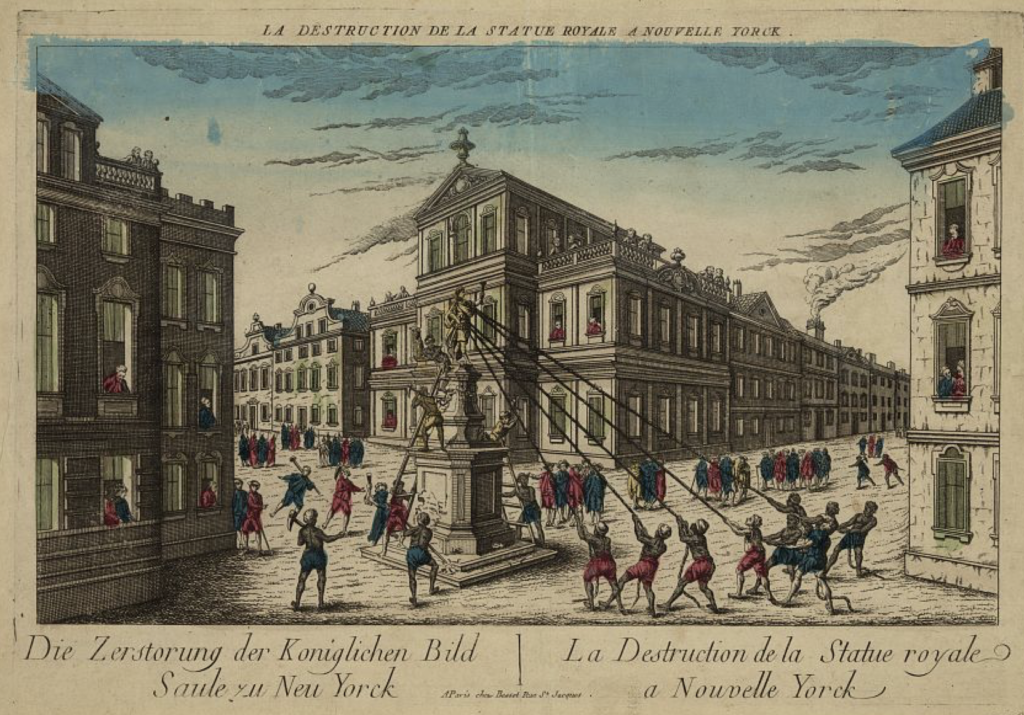

On July 9, 1776, angry New Yorkers violently tore down that statue of King George and, as the story goes, rendered his body into bullets used in the battles of the Revolutionary War.

Flash forward to 2020 — cities across the United States today are reevaluating the meaning of their own public monuments. Critics say that removing memorials to the Confederacy, for instance, work to ‘erase history’.

But a monument itself is not history lesson, but a time capsule of the motivations of the culture who created them.

And that’s why this story from 1776 resonates so strongly today. Public statues do have meaning. And for New Yorkers — in the run up to American independence — one statue represented oppression, servitude and annihilation.

In this episode, take a trip back to the city right before the war, when New York was split into those sympathetic to the Tories and those to the Sons of Liberty, an early organization dedicated to the liberty of the American colonies.

PLUS: The story lives on! Find out where you can locate artifacts from this story throughout the city today.

FEATURING: A young Alexander Hamilton, William Pitt the Elder, that rascal Cadwallader Colden and the enterprising ladies of the Wolcott household.

To get this week’s episode, just find our show on Stitcher or your favorite podcast streaming service. Or listen to it here:

The story of the destruction of the statue at Bowling Green spread far and wide, inspiring some less-than-accurate depictions of the event.

The Bowery Boys: New York City History podcast is brought to you …. by you!

We are now producing a new Bowery Boys podcast every week. We’re also looking to improve and expand the show in other ways — publishing, social media, live events and other forms of media. But we can only do this with your help!

We are now a creator on Patreon, a patronage platform where you can support your favorite content creators.

Please visit our page on Patreon and watch a short video of us recording the show and talking about our expansion plans.

If you’d like to help out, there are six different pledge levels. Check them out and consider being a sponsor.

We greatly appreciate our listeners and readers and thank you for joining us on this journey so far.

FURTHER LISTENING

After listening to this tale of the King George III in Bowling Green, check out these past Bowery Boys podcast episodes which also speak about some of the subjects featured on this show.

2 replies on “Tearing Down King George: The Monumental Summer of 1776”

This episode was OUTSTANDING! My partner and I just listened. So timely. I just shared with friends and am proud to be a supporter!!

I might be a bit late to comment here, but I’m fascinated by the ‘innacurate’ Andre Basset European drawing, and the fact that it seems to show slaves doing the actual pulling down.

I realize it has many, many mistakes in it (mostly from lack of visual references to work from at speed etc), but then so do many subsequent American depictions.

Some report or other must have prompted the artist to depict it this way, and it really wouldn’t surprise me if it was true that slaves did the actual work.

I cannot find any extra info about this anywhere, wondered if anyone here knows anything or can help clarify this?

I’m working on a graphic novel of Thomas Paine and this scene is in it. More details- Facebook- https://www.facebook.com/groups/368130724309879 Twitter- https://twitter.com/SbonesTompaine