On the upper floor — or flooah? — with the upper crust: Ladies coats at Sak’s Fifth Avenue in 1960, photo by Alfred Eisenstaedt (LIFE)

WARNING The article contains a few spoilers about last night’s ‘Mad Men’ on AMC, so if you’re a fan of the show, come back once you’re watched the episode.

A culture clash between New Yorkers from different races and classes came barreling through the storyline of ‘Mad Men‘ this week. While Peggy Olson had an awkward bonding moment with the new black secretary Dawn, a morbidly ill Don Draper took out his emotional tensions on the new Jewish copywriter Michael Ginsberg.

As revealed last week, Ginsberg is a ‘real’ New Yorker, living in a tiny apartment with his very devout father with a thick Yiddish accent. This week, Draper chastised the casual, Brooklyn-esque tone of Ginsberg voice, possibly implying a dig at the character’s Jewish roots. In response, Ginsberg defended his ‘regional accent’ and pointed out that Don, too, had an accent. The new kid eventually shines at a pitch meeting emulating a presentation style (and even vocal techniques) ripped from the Draper playbook

On a personal note, I’ve been fighting with accents my whole life, born with an Ozarks drawl only to develop the standard Midwestern ‘newscaster’ voice by high school, then living in New York for almost two decades and now slowly beginning to sound like it. So I found Don’s personal affront particularly interesting, as everything about him is a facade, including the voice. (I also went to school with fellow Missourian Jon Hamm, but that’s for another posting.)

Until last night, it never occurred to me that the secret to New York’s modern local tone — the many borough-specific variants of the New Yawk accent, if you will — was actually ‘discovered’, academically speaking, in a published study released in 1966, the year this season of ‘Mad Men’ is set.

Linguist expert William Labov was a Columbia University doctoral student in the early 1960s when he embarked on an extraordinary and influential study of the New York accent, the results of which were released as The Social Stratification of English in New York City in 1966.

The standard New York accent was historically presented as street jargon, whether it be the New York Times writing out the words of newsboys phonetically (“Dere’s tree t’ousand of us and we’ll win sure”) or the broad slang-filled movies of the Bowery Boys acting troupe (“Whadda ya hear! Whadda ya say!”). Upper class New Yorkers from old families frequently carried a New England lilt in their voices.

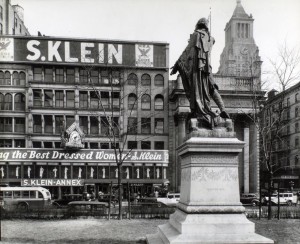

What seems inherent from comparing those two examples was flatly proved by Labov’s fascinating experiments done in three New York City department stores — the affordable S. Klein’s in Union Square, the higher priced Macy’s in Herald Square, and the very exclusive Saks Fifth Avenue — attracting shoppers from different social classes.

Below: Klein’s ‘on the Square’ in 1936, photo by Berenice Abbott.

I would have loved to have assisted Mr. Labov out with his experiments. Throughout the day, he asked employees from each store where the women’s coat department were located. In the case of these three stores, it was on the fourth floor. Or the fowth flooah or even the fowt flooah. When asked to repeat what they said, people would most likely restate ‘fourth floor’ with the -r more carefully said, as though it was their accent that had caused the confusion.

Those employees of S. Klein were far more likely to lose their -r sounds, while those from Saks were least likely. But Labov’s study found an additional quirk. On higher floors, where more expensive items were sold in each case, people more likely kept their -r sounds.

His conclusion found that “rhocity increased with the prestige of the department store” and that it even increased within the store itself. How the words were clearly pronounced and presented did not specifically depend on the geographical origin of the speaker, but on socioeconomic considerations. Labov concluded that New Yorkers of the 1960s generally disliked their own accents and subconsciously chose to mask it. “The term ‘linguistic self-hatred’ is not too extreme to apply to the situation,” he stated in his report. “As far as language is concerned, New York City may be characterized as a great sink of negative prestige.” [source]

Labov’s 1966 study is considered one of the most important linguistic findings of the late 20th century. Today Labov is considered the father of sociolinguistics. Whether his conclusions still apply today is a question for modern researchers. But they add an interesting new context to this burgeoning competition between Draper and Ginsberg, a symbolic competition between the ‘fake’ and the ‘real’.

3 replies on “‘Mad Men’ notes: The secrets of the New Yawk accent”

To find out if Labov’s conclusions apply today, simply ‘ax’ someone to say ‘ekcetera’. That may give you a clue. 🙂

Great column, as always. Funny, that some of us born speaking Brooklyn-ese added “Rs” to some words. I’m sure there are more, but I grew up thinking the nation’s capital was “WaRshington.”

And my father (born 1926, Queens) would say: “We need to fill the earl tank…”