The scene at Wooster and Prince Street on April 19, 2012.

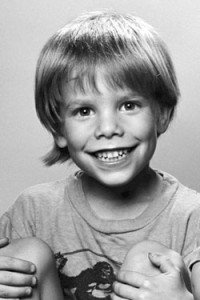

The world has changed since the disappearance of Etan Patz from the streets of New York on May 25, 1979. At least it seemed that way yesterday when the FBI and the New York Police Department reopened the cold case of the boy’s disappearance and focused its attentions on a building in SoHo at 127 Prince Street. Etan went missing after leaving his home at a few doors down, at 113 Prince Street, on the way to the bus stop.

The neighborhood today is a concentrated collection of boutiques, franchise clothing stores, art galleries, cafes and an Apple Store. The building that may hold the secrets to one of New York’s most famous unsolved mysteries holds a Lucky Brand jeans boutique on its ground floor.

Etan would be about my age now. But I have never lived in SoHo. For Etan, it was the only place he ever called home. The SoHo of today is a broad caricature of that neighborhood he lived in. It’s sunny and mostly welcoming now but oddly dispiriting. One block way is a two-story retailer entirely devoted to Crocs.

It’s a neighborhood that has changed dramatically in tone over the past thirty years, even if its appearance has remained almost identical thanks to its designation as a historic district in 1973. (Given the madness of development along the neighborhood’s western edge, could you imagine what would have happened here without it?) Its sleek, bustling character is of fairly recent invention, a perversion of the 1970s art and fashion scene which flocked here, attracted to the abandoned old factories and warehouses garbed in striking cast iron.

Below: Crosby and Spring Street, 1978 (Flickr/straatis)

The district was pulled from the jaws of destruction — Robert Moses‘ failed project, the strange and insane Lower Manhattan Expressway— in the 1960s, then became populated with adventurous young creatives drawn to the neighborhood’s relative isolation and large lofts. Former storage rooms for textiles and other dry goods became ideal for art galleries and performance spaces. The ‘cast iron district’ may have itself informed the creativity that flocked here. Gallery owners could think ambitiously. High ceilings, canyons of uniform metal, and stark cobblestone streets appealed more to the avant garde.

There was still something mysterious about SoHo in the mid-1970s, a time before high-end fashion became entrenched in the windows. It allowed artists and bohemians to thrive in a place that in many ways seemed off limits from the rest of the city, more rarefied. SoHo took on a different artistic hue from the East Village where art mixed with poverty. Quirky (and expensive) clothing boutiques soon arrived; Betsey Johnson, for instance, opened her first store in SoHo in 1978.

The elevation into a sort of edgy high culture was palpable enough that it soon seeped into pop culture. Between horrifying visions of death, Faye Dunaway traipsed the streets here in 1978’s ‘The Eyes of Laura Mars‘. Martin Scorsese paid homage to its eccentricity in his 1985 film ‘After Hours‘.

But SoHo would not have been immune to the New York’s deteriorating infrastructure of the 1970s. Or its escalating crime. While perhaps not unsafe during the day, this stretch of Prince Street where Etan would have walked in 1979 had far less foot traffic on a weekday, clearly free of today’s starving artists, latte sippers and jewelry and tee-shirt sellers. By 1984, when New York Magazine proclaimed SoHo was “on the verge of becoming a downtown Madison Avenue,” the crime rate was actually increasing. The depths of the neighborhood’s swift gentrification were clashing with reality.

It would take a financial upswing in the late 1980s and early 1990s for SoHo itself to change again. Wealthier residents moved in, as did high-end retailers — and then, slightly less-than-high-end retailers along Broadway. This forced out a great many of the original galleries, now drawn to a new area of warehouse-filled remoteness in West Chelsea.

When Etan Patz disappeared in 1979, the tragedy literally changed how Americans thought about missing children. The search erupted into a media frenzy with detectives fielding hundreds of false leads driven by lost-child flyers that blanketed New York City.

It became the “widest and longest search for a missing child undertaken by the city’s Police Department in decades” [source] and quite possibly the most publicized child abduction in America since the kidnapping of Charles Lindbergh‘s infant son in 1932. In 1983 President Ronald Reagan established National Missing Children’s Day on May 25, the day of Etan’s disappearance. He became the first missing child to adorn a milk carton.

And so, over 30 years later, this case now leads right back here to a building in SoHo a short distance from his home, in a place he might find unrecognizable and in a country transformed by his disappearance.

2 replies on “The missing: Revisiting the Etan Patz disappearance in SoHo and holding on to memories of a transformed neighborhood”

The mid-80s into the early 90s were really a decent time to go strolling in SoHo on the weekends. It was still generally uncrowded, still pretty hip, and the stores weren’t national chains. Today that whole area is a complete nightmare. But that’s true of most places that used to be fairly cool right up into the mid-90s, like the East Village and the rest of the Lower East Side and Tribeca and the Meatpacking District and even Chelsea, in its own way. But those days are gone and we have what we have, such as it is.

What does ‘still pretty hip and fairly cool’ mean when living in 1988? And what does ‘a complete nightmare’ mean in 2012 regarding a neighborhood? Are you saying living was better back then? I do miss smoking in bars.