“Such is the world, or, rather, one infinitesimal portion of the cosmos, in the year 2015, according to the ancient calendar, or 90 since the Terror.”

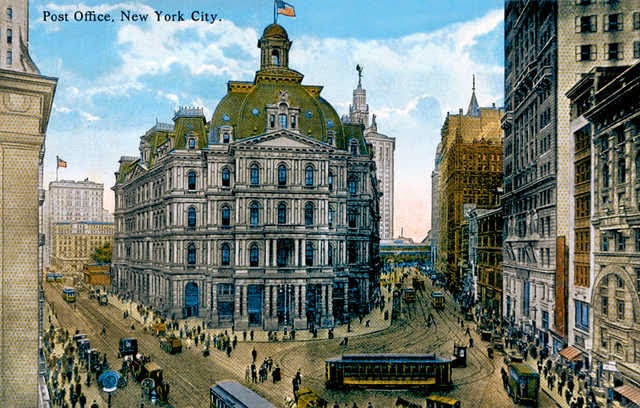

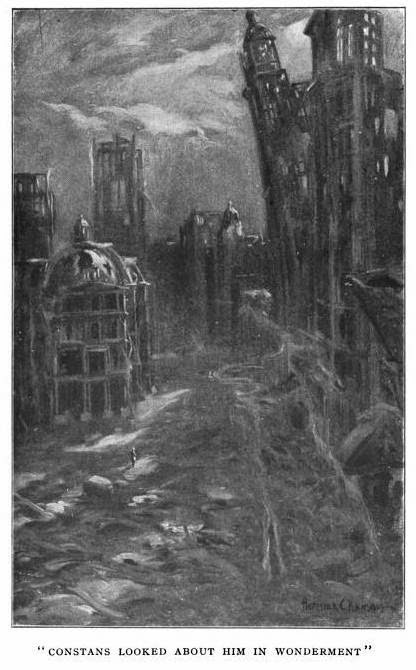

From the original illustrations of The Doomsman: a look up Park Row in 2015, a decrepit row of deteriorating structures. You can clearly see the ruins of old Post Office at the foot of City Hall Park. Compare this view to the photograph at the bottom of this post.

The destruction of New York City is a literary pastime that began in the late 19th century, usually in the hands of moralist writers seeking a little comeuppance upon the great evil of modern life.

By the year 1900, Manhattan had already been destroyed by nitroglycerin bombs (Park Benjamin Jr‘s ‘The End of New York,” 1880), left to waste in a future dystopia (John Ames Mitchell‘s The Last American, 1889), and cleansed with poison gas in a ‘revolutionary holocaust’ (Caesar’s Column: A Story of the Twentieth Century, written in 1890 by Congressman Ignatius Donnally).*

In 1906, the Episcopalian minister William Van Tassel Sutphen entered the fray with his own version of post-apocalyptic New York City in the novel The Doomsman, first serialized in Metropolitan Magazine.

What makes this book especially interesting today is that the breathless plot takes place in the year 2015. We’ve lived through that year so we can address what Sutphen got right. (The answer: nothing.)

Hole in One

Sutphen, an intellectual and New York literary sophisticate, is perhaps best known today as an early sports writer, best known for his observations on the sport of golf.

In 1898, he wrote the very Dr. Seuss-ian Golfers Alphabet. (“A is Arithmetic, handy to know/When the score figures up to a hundred or so.“) His most popular book remains 1901’s The Nineteenth Hole: Being Tales of the Fair Green, featuring humorous stories along the sporting course.

He was closely associated with Harper Brothers, writing and editing for the publishing house for most of his life. It was for Harpers that Sutphen wrote The Doomsman, his first non-golf book.

Doom and Gloom

The Doomsman is Anglo-Saxon fantasy, Game of Thrones lite, turning the New York metropolitan era into a landscape of wild vales and stockades. But its most interesting element is the depiction of a future Manhattan neglected and overcome, its ruins lorded by the vicious remnants of mankind.

Keep in mind however this is 1906 Manhattan.

This is the futuristic version of an old landscape. The novel’s version of a dismantled America should be familiar to anyone whose watched a recent disaster film or enjoyed an episode of The Walking Dead.

“For miles and miles the ruined city stretched away, a wilderness of brick and mortar. Here and there were areas of blackness and vacancy, where fire had worked its will.

The business section, with its substantial shops and warehouses, and the central district, made up of the clubs, churches, theatres and the handsomer private homes, remained intact. And yet, withal, the spectacle was a singularly mournful and depressing one, for nowhere were there any signs of life.”

It’s 2015, and New York City is now called Doom. At some point in the 1920s, a Great Change occurred, so instantly that few could prepare for the aftermath.

The wealthiest New Yorkers, “seiz[ing] upon the shipping in the harbors for their exclusive use,” fled via steamships. The remaining population were ravaged by the Terror, a combination of panic and disease, and left only a handful of survivors.

Most fled to the countryside but died there. All industry, “every form of thought and progress,” ceased to be. “The relapse into barbarism was swift.”

People escaped into new walled encampments and quickly divided into medieval classes. Walled fortifications appeared over the ruins of the outer boroughs, Long Island and Westchester.

Our hero Clemens is raised at Greenwood Keep (pictured above), some kind of stockade presumably in the area of Greenwood Cemetery.

The area is constantly terrorized by The Doomsmen, inhabitants of the ruins of Doom. When Clemens’ own home is savagely destroyed in an attack, Clemens vows to venture into Doom and seek his revenge on the nefarious warrior Quinton Edge.

Days of Future Past

In 1906, the year Doomsman was published, there was not yet a Woolworth Building, but downtown Manhattan was in the midst of a colossal building boom unlike any other.

The author plays upon the fears of the day. Unusual gases seeped from the broken sidewalks. Old stone adornments fall the sky, almost killing our hero.

New York’s skyscrapers still exist in 2015, but all were empty, hollowed out and falling apart; one skyscraper on Park Row “had settled and was leaning over at a terrifying divergence from the perpendicular.”

He eventually arrives at the main branch of the New York Public Library (above) — lion-less and half-completed in 1906 — and meets the tempestuous young Esmay whom he will eventually fall in love with.

With a little detective work, you can figure out many of the real-life locations depicted here. For instance, the walled city Croye, “the principal city of this western hemisphere in the year 2015,” is actually Yonkers. Perhaps because it’s already so ancient looking, one landmark retains its name — the High Bridge.

But most of the action takes place in Citadel Square, alongside the Palace Road (Broadway).

That’s actually Madison Square, which has become the encampment of the Doomsmen, many of whom are holed up in the White Tower — most likely the medieval-looking tower upon old Madison Square Garden.

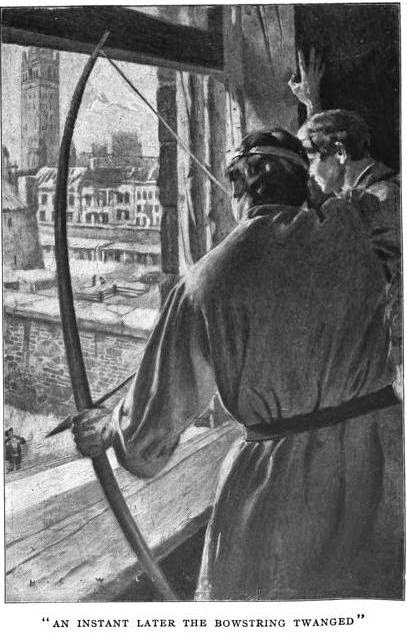

Our hero takes up a home on the fourth floor of the peculiar building to its southern side, a structure that would have been sparkling new in the mid 1900s. “The building had been constructed upon a narrow, triangular plot of land, and its ground-plan bore a fanciful resemblance to the shape of a flat-iron.” From this vantage within the Flatiron Building, Clemens is able to launch arrows upon his enemy.

But perhaps its strangest detail comes from another obsession of the late 19th century — electricity. The Doomsmen worship The Shining One, an electric dynamo in an abandoned power plant. A crazed priest has been able to reconnect the power and turn — get this — an electric chair into the central relic of worship!

The Doomsman is hardly an unfairly forgotten masterpiece. Its racial and ethnic politics are frankly repellent, its female characters mostly stock characters of helpless maidens and selfish harpies. The prose is occasionally cinematic — that’s cinema in 1906 — perfect for a silent film adaptation that regrettably never happened.

At right: The original cover of the book featured the Flatiron Building

For a modern audience, it’s most interesting for its descriptions of Gilded Age ruin, of a city that never developed to embrace automobiles.

In a book that’s so conventionally swashbuckling, it’s startling to read passages like, “Hats and garments, cash-boxes and accountbooks, littered the hallways and were piled in little heaps at the entrances of elevators.”

The book is in the public domain if you would like to read it for yourself.

**If you’re looking for more Victorian era tales of future destruction, check out this paper by Mike Davis and other authors called ‘Dark Raptures’.

Below: A look at City Hall Post Office and Park Row before everything went to hell. Compare with the image at the top.

Originally published in 2015