Our modest little series about some of the greatest, notorious, most important, even most useless, mayors of New York City. Other entrants in our mayoral survey can be found here.

The 1910s were a rough time to be mayor of New York City. The decade’s first mayor, William Jay Gaynor, took an assassin’s bullet in the neck and an entire term to die from it. A second mayor — in fact, New York’s youngest mayor ever — would not live to see the end of the decade either.

We covered Gaynor’s unusual tenure in the job in a prior entry. Former army Col. Ardolph Loges Kline stepped in to fill the remainder of Gaynor’s term, a duration of less than four months. Kline, former president of the Board of Aldermen (an equivalent of today’s city council), was remarkably enough a replacement for that job too. He stepped in after first Board president, a man whom I will shortly introduce below, vacated the post.

Although fairly insignificant, Col. Kline holds a distinction that Rudolph Guiliani must loathe — Kline is the last mayor to hold an additional elected office after leaving City Hall. (He became a U.S. representative for a single term.) Keep in mind this significance; in the early days of New York, the mayor’s seat was a mere stepping stool to a host of elected jobs. Kline seemed to take that stepping stool with him when he departed on the first day of 1914.

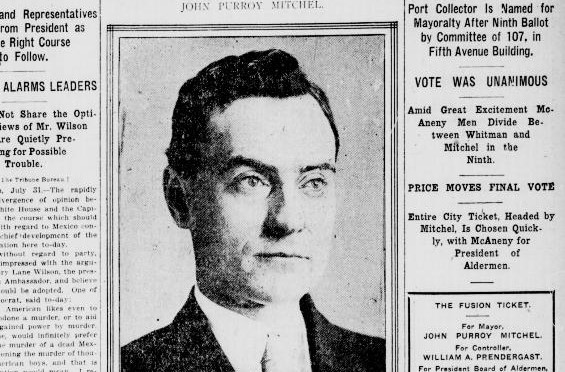

Kline stepped aside in 1914 for the newly elected John Purroy Mitchel, an ambitious young man who at 34 become the city’s second youngest mayor. (Hugh Grant — that’s Hugh J. Grant — was the youngest at 31.) He would forever be known as The Boy Mayor.

Mitchel had a meteoric rise not too dissimilar to our former governor Eliot Spitzer. A graduate of Columbia University and the New York Law School, Mitchel was thrust into the spotlight in cases that frequently pit him against the all-powerful leader of Tammany Hall, Charlie Murphy.

In 1907, all of 28 years old, Mitchel brought down the borough presidents of Manhattan and the Bronx in one fell swoop, the ringleaders of a corrupt contracting scandal. He quickly became known for his reform-heavy, almost naive take on civic responsibility, a refreshing breath in this era of Tammany Society. Mitchel was quickly elected to the president’s seat of the Board of Aldermen, in the same election that brought Gaynor to City Hall.

As Gaynor was losing the graces of Tammany, Mitchel swiftly proved himself a thorn in the side of the shifty New York police force. When it was discovered that a prominent police chief Charles Becker, on the Tammany payroll, had murdered a Jewish casino owner on July 1912 in efforts to ‘shut him up’, Mitchel used the public outcry to sweep the precinct halls of mass corruption.

Mitchel’s rising star was impervious to Tammany attacks and was elected the new mayor, the nominee of a fusion party.

In his inauguration speech, he makes the startling announcement: “It will not be necessary for us to go to the people of the city every day and tell them what we propose to do. It will be better for us to wait a little while and then to go to them and tell them what we are doing or have done.”

Some of the reforms he brought into play include a standardization for government works and a innovative city development zoning plan.

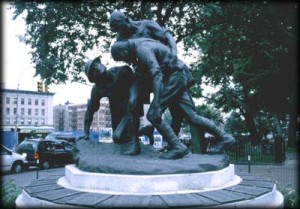

Unfortunately, history almost repeats itself with another crazy assassin. Four months into his term, a disgruntled 72 year old man by the name of Michael Mahoney fired a shot at Mitchel at City Hall. But unlike his predecessor Gaynor, the mayor was not hit and he and his entourage wrestled the disturbed man to the sidewalk.

The real attack, however, was yet to come — and no surprise, from Charlie Murphy. Although Mitchel had continued with his vow to eradicate police corruption, an educational reform policy was viciously attacked from both ends, from Murphy’s Tammany pawns and from William Randolph Hearst‘s New York World. The attacks worked; Mitchel, a Catholic, lost the support of the poor Irish Catholics who believed the education reforms would only benefit the rich. By the end of his term, the Boy Mayor was soundly defeated by John Francis Hylan — bringing Tammany back to City Hall.

Undetoured, Mitchel changed career course. World War I had raged throughout his tenure as mayor, and he strongly believed in the importance of military service. Still a young man, he joined the Signal Corps Army Air service as a pilot in 1918. Unfortunately nobody would ever know whether he would bring his brilliance and ambition to the armed forces as on July 6, 1918, fell out of his plane during a training session in Louisiana, after apparently failing to fasten his seat belt. A curiously ridiculous and tragic end to a unique New York personality.

At the Engineers Gate in Central Park on Fifth Avenue sits a very, very gold bust of Mitchel. The bust was made by Adolph Weinman, the go-to sculpture guy of iconic New York architects McKim Mead and White. He’s also honored by Mitchel Square in Washington Heights (with a monument to World War I, see below) and Mitchel Air Force Base in Long Island.

Strange fact: allegedly, his aerial death was the partial inspiration for Gary Cooper‘s demise in the silent film ‘Wings’, best known as the first ever Best Picture Oscar winner.