Connie’s during the day, with the Tree of Hope directly in front of it

FRIDAY NIGHT FEVER To get you in the mood for the weekend, every other Friday we’ll be featuring an old New York nightlife haunt, from the dance halls of 19th Century Bowery, to the massive warehouse clubs of the mid-1990s. Past entries can be found here.

NIGHTCLUB Connie’s Inn

In operation: 1923-1933

The strange and sad irony of Harlem nightlife in the 1920s — during the neighborhood’s height of creative powers — is that the biggest clubs featured the world’s top African-American musicians, but only a white audience could go hear them. This ridiculous arrangement, however, did allow many performers a unique forum to launch their careers, for this string of whites-only establishments soon became the hottest spot in Jazz Age New York. A district of these clubs soon took on the moniker Jungle Alley.

Concentrated on 133rd Street between Lenox and Seventh avenues, Jungle Alley was a place for downtown white Manhattanites to dabble in the saucy, ‘dangerous’ sounds of jazz as performed by some of the most talented people in the world. Elegant, new Pontiac and Franklin sedans lined the street delivering partygoers to the likes of The Cotton Club and Small’s Paradise, the two biggest names among virtually dozens of establishments on Jungle Alley. And of course a couple blocks away at 131st and 7th Ave, in a basement near the Lafayette Theatre — there was Connie’s Inn, in no way as plain as its name suggested.

Cotton, Small’s and Connie’s — these were the big three of Jungle Alley.

The Connie in question is Conrad Immerman, a German immigrant who, with his brother George, moved to the neighborhood and opened a chain of delicatessens. (According to lore, a delivery boy at one of those delis was none other than a young Fats Waller.) However, with prohibition, it became far more profitable to alter their business plan to include speakeasies. By 1923, the brothers had opened Connie’s at one of the most prominent corners in Harlem. Right next to it sat the famous Tree of Hope, a large chestnut who the alleged powers of good fortune for those who rubbed it. (A remnant remains on the stage of the Apollo Theatre.)

It certainly worked for Connie. His establishment soon rivaled the Cotton Club as the hotspot for New York’s trendier white crowd.

Why would Immerman exclude blacks? One source suggests this wasn’t Connie’s natural inclination: “Connie was not a bigoted man. Connie’s reason for exclusivity policy is a matter of profit; he assumed his white downtown clientele did not wish to sit, cheek in jowl, with African Americans.” Faint justification today. Connie’s success spawned a virtual industry of whites-only clubs in the neighborhood. He bolstered the segregation by giving in to it passively. Eventually, though, Connie’s would open for black audiences — after hours, when the downtowners had returned to their homes.

Connie’s attracted the best and the worst of the underworld, “a shady clientele of gangsters and molls, rumrunners, and bathtub bootleggers” according to one source. A black newspaper the New York Age says, “Immerman’s is opened to Slummers; Sports; “coke” addicts, and high rollers of the White race who come to Harlem to indulge in illicit and illegal recreations.”

Connie’s attracted the best and the worst of the underworld, “a shady clientele of gangsters and molls, rumrunners, and bathtub bootleggers” according to one source. A black newspaper the New York Age says, “Immerman’s is opened to Slummers; Sports; “coke” addicts, and high rollers of the White race who come to Harlem to indulge in illicit and illegal recreations.”

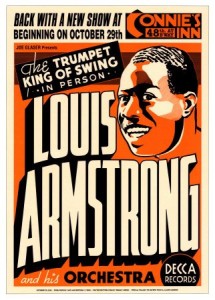

Slummers and sports alike packed into Connie’s 500 seat club, elegantly ornamented, one of the classier looking establishments of Jungle Alley. The stage could fit a couple dozen dancers, a rollicking jazz orchestra and a few prime performers sewn together into a variety of spirited production numbers. Winding across Connie’s stage were artists like Moms Mabley, Fletcher Henderson and Louis Armstrong.

One stage show by Fats Waller, eventually titled Hot Chocolate, was successful enough that it transplanted for a successful run on Broadway. Armstrong would recall racing between the Broadway stage — where he would perform ‘Ain’t Misbehavin’ every night — and Connie’s, where he was a contract performer.

One stage show by Fats Waller, eventually titled Hot Chocolate, was successful enough that it transplanted for a successful run on Broadway. Armstrong would recall racing between the Broadway stage — where he would perform ‘Ain’t Misbehavin’ every night — and Connie’s, where he was a contract performer.

Armstrong was uncomfortable with the mob-controlled world of New York nightlife, and Connie’s place was no exception. One night during a performance in Chicago, he was compelled to return to New York to perform for Connie.

According to an Armstrong bio, Louis claims that a gangster Frankie Foster “was sent over to my place to see that I catch the first train out of New York…I said ‘New York? Why that’s news to me.’ Foster said, Oh yes, you’re leaving tomorrow morning.’ Then he flashed his big ol’ pistol and aimed it straight at me. With my eyes big as saucers and frightened too, I said, ‘Well, maybe I am going to New York.”

Connie’s was a haven for mob activity; Connie’s brother George was even kidnapped for a time during a ‘disagreement’. But then, everybody was acting funny in those desperate final days of Prohibition. By 1933, Connie’s had closed its door, not fit for a world of legal entertainment.

6 replies on “Jungle Alley and wild nights at Connie’s Inn”

cool i’m the first to comment! 🙂

What a fun read!! Great work. Do you remember you sources for this

Connie Immerman was the first to dub, employee; Ada Smith “Brickhead” on

account of her hair colour; Brickhead would later cruise to immortality

Please send everything you know about Connie’s Inn to A C Lewis, his great Nephew. It should all be collected.

thank you

Her name is Bricktop.

Good morning, I love this post. I also need to reproduce that photo of Connie’s Inn. Can you please tell me where to find it (and if you know, where I can apply to get the permission to use.)

Thank you very much, Maureen Footer