BOWERY BOYS BOOK OF THE MONTH Each month I’ll pick a book — either brand new or old, fiction or non-fiction — that offers an intriguing take on New York City history, something that uses history in a way that’s unconventional and different or exposes a previously unseen corner of our city’s complicated past. Then over the next month, I’ll run an article or two about some of historical themes that are brought up in the selection.

The Measure of Manhattan:

The Tumultuous Career and Surprising Legacy of John Randel Jr.

by Marguerite Holloway

WW Norton & Company

The man at the center of Marguerite Holloway’s ‘The Measure of Manhattan’ is a genuine riddle.

The surveyor John Randel Jr. rarely wrote about himself, jotting down observations of land elevation and incompetent workmen as he mapped out the legendary grid plan along the island of Manhattan.

This ambitious task, occurring early in his career, would assure his place as a pivotal, if quiet, figure in American history. During this period, he is studious, focused and, let’s just say it, a mite uninteresting. But just as the grid is completed, Randel’s personal story comes to life.

A traditional historian might not know what to do with the life of Randel, a man who ages into astonishing eccentricity and temperament. But.Holloway, a journalism professor at Columbia University, treats this story as a two-fold mystery, turning something that could into a real unexpected — and often unpredictable — treat.

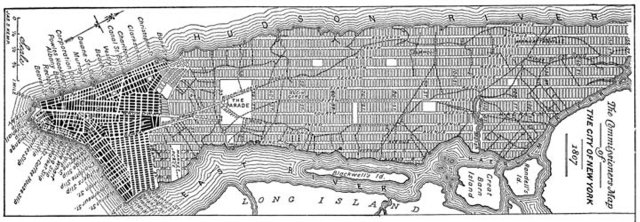

Her first concern is the grid itself, the orderly row of streets and avenues that arose out of the former hills and streams of Manhattan, following researchers who are attempting to determine how drastically the landscape has been altered over the years.

Evidence of the original surveying job — which sliced through private property and reorganized nature into something unrelenting and orderly — can be found in Central Park. In fact, a bolt sits lodged in a rock, the last remaining evidence of Randel’s assiduous work. It’s an astonishing discovery.

As is Randel, the man who probably put it there. The young surveyor, taken under wing by the well connected DeWitt family at the start of the 19th century, worked on the grids to Manhattan and Albany before he was 30 years old, braving the wrath of farmers to mark rectangles in the landscape. So unusual was the island’s terrain that Randel invented his own surveying equipment specifically suited for the job at hand.

But even as Holloway goes deep into Randel’s technique, there appears to be a vacuum at the center of the story. Randel’s personality seems opaque, even non-existent. But wait.

The most fascinating aspects to Randel’s character come after the grid is completed, when the surveyor attempts to cash in on his remarkable accomplishment. He naturally attempts to sell copies of his maps but, in these heady days before copyright, is thwarted by a competitor who basically duplicates his work

From that point, he seems to spend as much time in lawsuits as he does doing field work. He goes to work on an upstate length of the Erie Canal, only to annoy his peers and tarnish his reputation. Is it professional jealousy at Randel’s enormous skills, or is the great, embittered surveyor becoming obstinate?

As Benjamin Wright, canal engineer and enemy of Randel’s, once said of his rival in 1824: “I think him the most complete hypocritical lying nincompoop (and I might say scoundrel if it was a Gentlemanly word)…..”

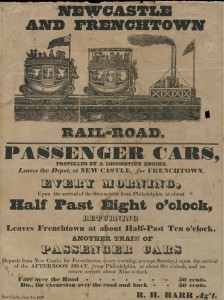

At left: A notice for another of Randel’s great projects, the New Castle and Frenchtown railroad, the first railroad in Delaware

Far from a career of increasingly applauded works, Randel becomes stepped in controversy at every turn, even as he moves from canals to railroads. He’s perpetually strapped for cash, even attempting to build his own estate (amusingly called Randelia) with unfortunate results. In a desperate act of “piracy”, according to the author, he even attempts to collect his very own tolls from a canal he himself surveyed and engineered!

Holloway, employing an extraordinary depth of research, describes a man of great talent who gets ripped asunder by America’s rapid growth, defined not by accomplishment but debt. In a way, this is as pure an American story as it gets.

The tale often pulls back at times to modern day, constantly reminding us of Randel’s most stunning accomplishment, a New York grid plan so implanted that it seems impossible to imagine that anything else ever existed here. In particular she turns her focus to Eric Sanderson and his amazing 2009 Mannahatta project, pulling a reverse-Randel in trying to map out the original landscape as it appeared in the year 1609.

Randel returns to New York near the end of his life for the industrial exhibition held at the Crystal Palace in 1853, America’s first great show of its technological prowess. It is here that Randel reveals his last, greatest idea — an elevated railroad transporting passengers up and down the length of avenues he had himself marked over forty years earlier.

His visionary ideas were rejected. Over fifteen years later, well after Randel’s death, New York built an elevated railroad anyway.