Sergey Kadinsky is our city’s resident Aquaman. His Hidden Waters of New York City was the big New York City exploration guide book of the spring. In a city often characterized by glass, steel and asphalt, it’s magical to consider the metropolis almost like a human body, comprised and reliant upon water for its well-being.

As though armed with a magical divining rod, Kadinsky identifies almost every significant body of water that ever existed in the five boroughs — from ancient reservoirs to the most obscure Staten Island pond — providing modern context and directions for locating them  using public transit.  It’s a combination history book, hiker’s guide and trip planner.  My copy is presently dog-eared in about twenty places with living streams and lakes that I intend to visit this summer for my own personal mini vacations.

But the waterways that are no longer here are, in a way, even more intriguing, highlighting how New York was often sculpted around bodies of water before they were filled in or buried with the modernity of the city.

And there are a surprising number of old waterways that have disappeared relatively recently. For instance Jackson Pond in Queens. According to Kadinsky: “In 1966, the lake was dried and covered with concrete after the city determined it to be an unsafe ice-skating site.” Oh, but a Jackson Pond Playground sits upon the ghostly outline of this forgotten water today!

How do you even begin putting together such an ambitious project? Kadinsky is well suited for the task. He’s a long-time Queens resident, staff member at the New York Parks Department and an adjunct professor of history at Touro College. I asked Kadinsky a few questions about how his project came together:

Your book really identifies New York’s inescapable connection to water in almost every aspect of its history. How did you develop the idea to find every water sources (past and present) and put them together in a guide book?

For more than a decade preceding the book, I’ve worked as a Gray Line tour guide, newspaper reporter and Touro College adjunct. These experiences gave me an ability to tell a story in a an easygoing, detailed, and captivating manner.

In my spare time, I led tours and contributed stories to Kevin Walsh’s Forgotten-NY, a blog that has become a book and subject of tours and lectures. It inspired me to think of a specific hidden city element that I felt was not receiving its due.

Seeing the success of Sharon Seitz and Stuart Miller’s book Other Islands of New York City, I remembered my childhood exploring the backyard brooks of Riga, Latvia, and my parents’ home a block away from Meadow Lake in Queens and a rare grid-defying street on their block. I then recognized that I’ve found my niche.

That’s how Hidden Waters of New York City came to be. Other Islands is a blend of history, travel, and geology, with a journalist’s eye for detail and research. I followed its method in documenting the hidden waterways.

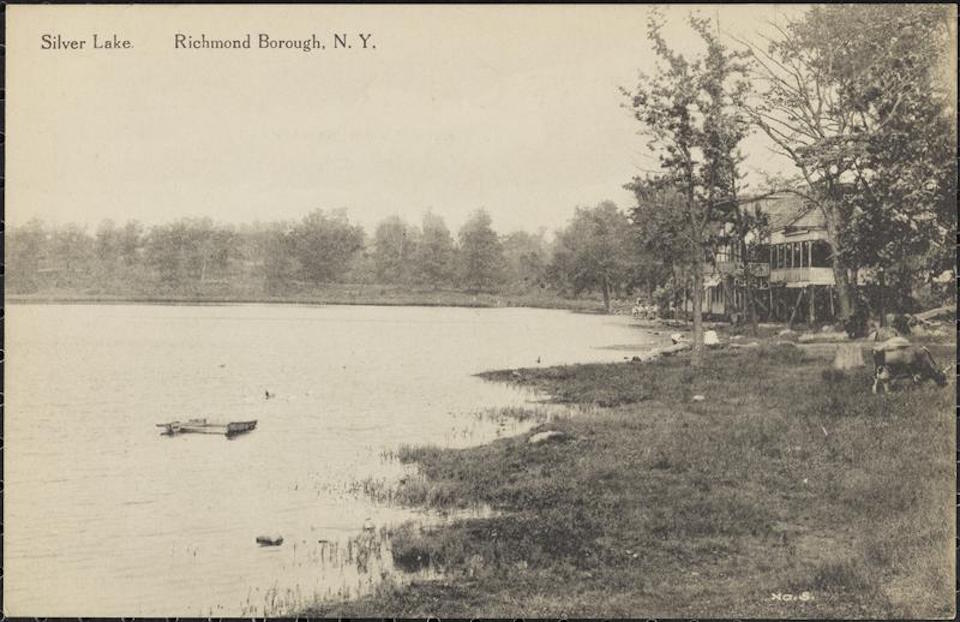

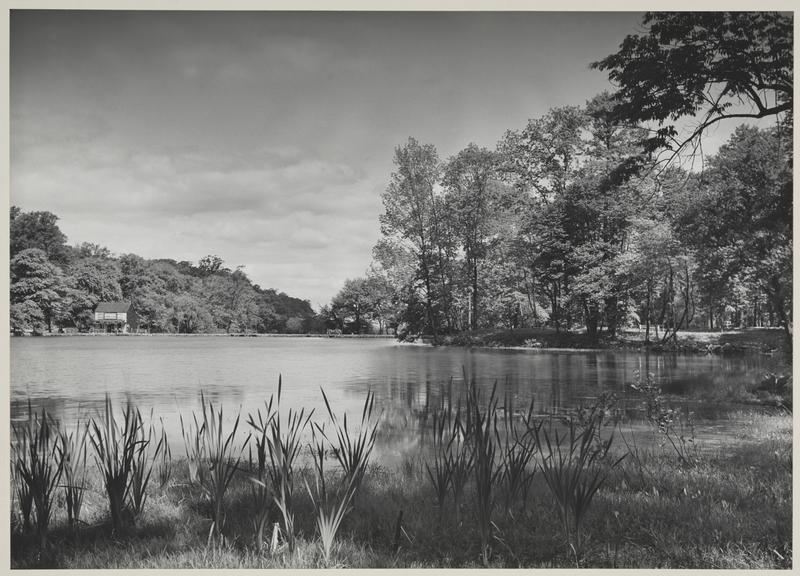

Silver Lake in Staten Island, photographed here in 1915 (and featured on pgs. 246-248 in Kadinsky’s book. Photo courtesy Museum of the City of New York

Hidden Waters feels something like a hiker’s guide to the city. How much walking around and on-foot exploration did you do while researching it?

As a historian and Parks Department analyst, I had access to old maps, reports, and photographs. There’s plenty of exploration that you can do at your desk or online. The Municipal Archives, New York Public Library, and Museum of the City of New York have excellent online resources on the city’s past. Finally, for GIS aficionados, the DoITT NYCity Map is second to none, followed my the NYPL Map Collection, and MCNY’s Mapping Staten Island online exhibit.

The path of old Minetta Creek from Egbert Viele’s Sanitary & Topographical Map of the City and Island of New York (1865).Â

Perhaps the most famous body of water in Manhattan in one that doesn’t really exist above ground – Minetta Brook. You’ll find its name everywhere and, as you mention, it’s dutifully traced by tour guides. What accounts for its appeal and does it truly exist as strictly an underground stream today as some claim?

Minetta Brook’s place in local lore goes back to the Native period, when it was believed to be possessed by a spirit. The neighborhood’s love of history and storytelling ensured that it would never be forgotten, surveyors laid out the streets and with local culture in mind, Minetta Lane and Minetta Street appeared on the map.

In the 19th century following its burial, flooding in basements built along its former course was a persistent problem. Engineer Egbert Ludovicus Viele dutifully noted and mapped these floods and ascribed them to Minetta Brook. He preceded me by 150 years in tracing Manhattan’s hidden waterways.

The 1938 extension of Sixth Avenue though Greenwich Village created small triangular parks near the brook’s former course- another opportunity to restore it to the map with Minetta Green and Minetta Playground. Historical preservationism, tourism, and a way of imagining a pre-urban Greenwich Village, all appeal to Minetta Brook’s popularity.

I do not think that the brook is flowing today underground along its former course. Its sources in the Flatiron District have been covered entirely with buildings. Streets running atop its course have sewers that do not follow the stream bed’s path. Nevertheless, the soil is much softer where creeks once flowed, and that helps explain for the flooding and groundwater. Even the famous well at Two Fifth Avenue could simply be ground water not necessarily associated with Minetta Brook, though the location makes sense.

Flushing Creek, with the sites of the old World’s Fair in the distance.

What is personal favorite body of water in the New York five boroughs (exempting the Hudson and East Rivers of course)?

Flushing Creek, because it’s a block away from my parents’ home and a five minute drive from my home. Unlike Gowanus Canal, Newtown Creek and Bronx River, this creek does yet not have a grassroots citizen-led conservancy group. The creek flows through a series of conditions such as a nature preserve, a recreational lake, a canal beneath highways, a tunnel, Willets Point, and into Flushing Bay.

The creek was a former salt marsh turned ash dump turned fairground turned park. There was talk in 2008 of daylighting the underground sections of it, but heavily used soccer fields are in the way. The creek was also slated for a grand prix racetrack in the 1980s and an Olympic venue in the past decade.

Adding to the subject are the creek’s tributaries, Mill Creek in College Point, Kissena Creek, and Horse Brook, which also are worth mentioning considering their rich histories.

You mention a great number of old waterways that were completely unknown to me. What was the most surprising discovery you made in your research?

This one is very close to home, Coe’s Mill on Horse Brook, which was demolished in 1930 to make way for what would become the Long Island Expressway.

Not enough books mention the English settlers who lived in New Netherlands having fled England and New England in search of religious freedom. Feeling a lack of respect and recognition from the Dutch, they petitioned England to annex the colony. It was like our own Crimea.

Unlike the Bowne House in nearby Flushing, nothing is left of Coe’s Mill. The mill provided food for the settlement of Newtown, one of the original towns of Queens that is now known as Elmhurst. Seeking a path of least resistance when it came to acquiring land for a road, the city built the Long Island Expressway atop the filled stream bed.

A year ago, I wrote a letter to Councilwoman Julissa Ferreras-Copeland, whose district covers this site, requesting to rename a nearby footbridge after the mill, and I have yet to hear back from her.

Alley Pond Park has the creeks and scenery but because it has highways running through it, it’s difficult to appreciate the place. Even deep in the woods where you can’t see any civilization, you hear cars whooshing nearby. That’s why the Greenbelt in Staten Island is truly the get away park in the city. It has forests, creeks and ponds, but no sounds of motorists driving past.

Check out Sergey’s truly excellent Hidden Waters Blog for more information on New York’s fantastic water sources. His book is currently on book shelves

2 replies on “Hidden Waters of New York City: Interview with author Sergey Kadinsky”

[…] In a recent interview, I lamented that Flushing Creek does not have a grassroots support group similar to the ones for Gowanus Canal, Newtown Creek and Bronx River. On the bike tour this past Sunday, I learned that it does have an advocacy group: Guardians of Flushing Bay. You can follow them on Facebook for upcoming events. […]

[…] In a recent interview, I lamented that Flushing Creek does not have a grassroots support group similar to the ones for Gowanus Canal, Newtown Creek and Bronx River. On the bike tour this past Sunday, I learned that it does have an advocacy group: Guardians of Flushing Bay, which also speaks for Flushing Creek. You can follow them on Facebook for upcoming events. […]