This Monday (May 27, 2019), a Memorial Day observance will be held from 10 a.m to noon at the Soldiers and Sailors Monument in Riverside Park. In honor of the holiday, we’re rerunning this 2015 article on this oft-forgotten monument.

The Soldiers’ and Sailors’ Monument on the Upper West Side has been the centerpiece for Memorial Day commemoration for decades. Unless you actually live by it, you probably have not been there in years, if at all. It’s a vastly under-appreciated landmark, occasionally vandalized and certainly in need of work. [For more on the history of Riverside Park, listen to our podcast episode: Heaven on the Hudson.]

It owes its form to the great Gilded Age fervor for classical beauty and the aesthetic appeal of Beaux-Arts architecture. Grand war memorials were sprouting up all over New York during this period, most notably he Soldiers’ and Sailors’ Arch in Brooklyn’s Grand Army Plaza (1892) and Prison Ship Martyrs Monument in Fort Greene (1908). Then there’s Grant’s Tomb (1897), which owes its existence more to the General’s military career and not so much his scandal-filled presidency.

And similar monuments of such colossal proportion were erected in other cities including Hartford (1886), New Haven (1887), Allentown (1899) Indianapolis (1902), Baltimore (1909) Syracuse (1910), Pittsburgh (1910), among many others.

Monuments are dandy indicators of civic pride but many were inspired by practical necessity. Most Union veterans were in their ’50s and ’60s by this time many of these memorials were planned. Those that grew up after the war– the sons and daughters of war heroes — wanted to recognize the achievements of a previous generation. Many of these men (Grant being the notable example) were now prominent citizens in New York.

Its also not a coincidence patriotic feelings were swelling during this period due to conflicts like the Spanish-American War which would later demand their own memorials like the powerful Maine Monument, unveiled in 1913.

Riverside Drive might seem a curious place to put a Civil War monument. In fact, its location inspired a bit of a civic war itself from the moment it was first planned in 1893. “THE MONUMENT FIGHT AGAIN” proclaimed the New York Times in 1895, reporting on a rivalry between members of the Upper East Side Association and the Upper West Side Association.

I mean, in 1895, didn’t it make sense to place it on Fifth Avenue, the most prominent and wealthy street in the world? Proponents chose Fifth Avenue and 59th Street, the entrance to Central Park, as the ideal spot. “It is rather amusing to hear …. grounds for opposition in view of what was said in front of the Commissioners when the west side men wanted to locate the monument on the Riverside Drive and Seventy-Second Street…..[T]hey charged that the Plaza was not suitable because the monument would be surrounded by buildings that would dwarf it.”

Supports of the Riverside site claimed that the foundations would not be sturdy enough near the park, an amusing remark given the skyscraper boom which would take over Midtown Manhattan in the 20th century. In particular, naval officers bristled at the Fifth Avenue site which was almost as far from the site of water that one could get in Manhattan.

Had the eastsiders won, we would have gotten a Soldier’s and Sailors Monument that looked like this on the spot of today’s Grand Army Plaza:

By 1899, years after the project was conceived, proponents of the west side finally won out. The monument was planned for a spot in the newly developed Riverside Park known as Mount Tom, a “very beautiful little knoll of natural rock,” believed to have been a spot of quiet contemplation for one Edgar Allen Poe (who lived nearby in 1844). That was at Riverside Drive and 83rd Street. Eventually that too was deemed inadequate, and the preparations were then moved to the present location at 89th Street.

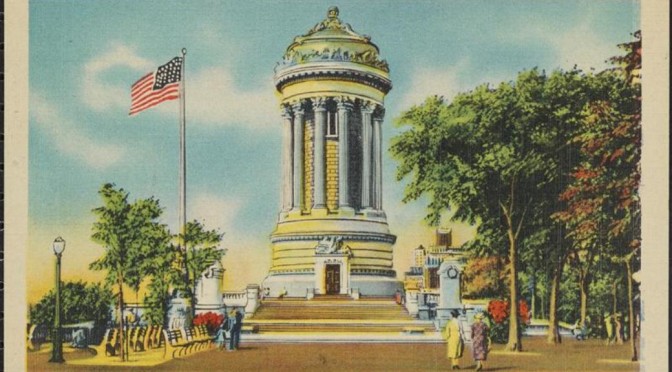

Given the new location, the monument was redesigned by the firm of Straughton and Straughton as a circular temple adorned with Corinthian columns. The Soldiers and Sailors Monument was officially dedicated on Memorial Day 1902:

Here are a couple views of its dedication ceremony in 1902:

The final monument is absolutely beautiful, of noble design, but was not well constructed. Repairs were necessary less than five years later, and the structure has gone through several alterations. This New York Times article gives you a look inside the monument and reviews some current efforts to rescue the building from further deterioration.

The weather’s supposed to be spectacular this holiday weekend, so make that a good excuse to visit this unusual and charming little memorial.

And finally, a mysterious post card from the New York Public Library collection. Note the caption: