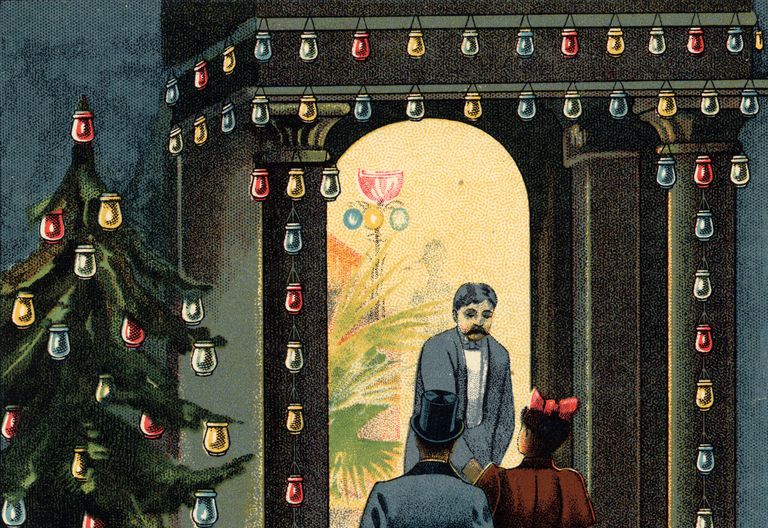

The world’s very first Christmas tree with electric lights was displayed in 1882 at the home of Edward Hibberd Johnson in the Murray Hill neighborhood of New York City.

Not only did it glow with this innovative new form of illumination, this Christmas tree also spun around, revolving like a flashy new car at an automobile expo.

Two years later in 1884 the New York Times looked back fondly upon this greatly advanced version of the Christmas tree:

“The tree was lighted by electricity and children never beheld a brighter tree or one more highly colored than the children of Mr. Johnson when the current was turned and the tree began to revolve.

“It stood about six feet high, in an upper room, and dazzled persons entering the room. There were 120 lights on the tree, with globes of different colors, while the light tinsel work and unusual adornment of Christmas trees appeared to their best advantage in illuminating the tree.

“The set of lights were turned off and on at regular intervals as the tree turned around. The first combination was of pure white light then as the revolving tree tree severed the connection of the current that supplied it and made connection with the second set, red and white lights appeared. Then came yellow and white and other colors.”

The children of Mr. Johnson were witnessing a revolution. Yes an actual revolution – of the tree itself – but the beginning of an entirely new way of celebrating the holiday.

Surrounded by his wealthy investors, Thomas Edison gave the first public demonstraton of the incandescent lightbulb on December 31, 1879.

Now, believe it or not, New Yorkers were already accustomed to electric illumination during the Christmas season. The major Manhattan shopping districts were already exposed to stadium-like arc lighting, a primitive form of electric light that was too harsh and intense for everyday usage.

But Edison’s invention was vastly superior and it wouldn’t just drive away the dark. In its compact size, its durability and eventual convenience, the lightbulb would elaborate on one of candlelight’s most appealing components – mood.

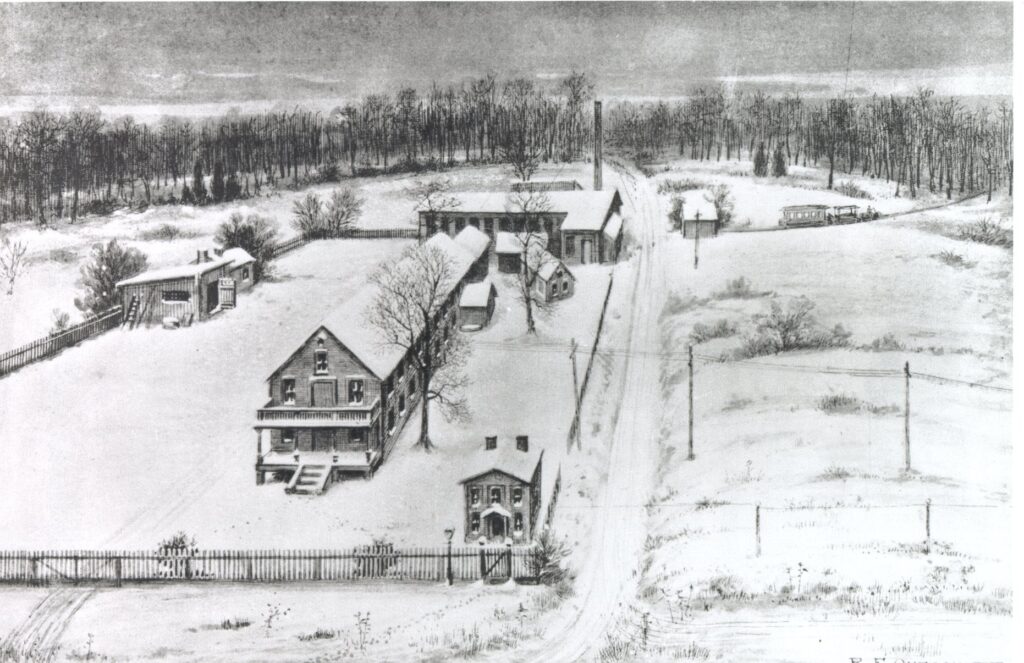

The next year, on December 20, 1880, Edison had additional investors out to Menlo Park, and they were greeted with an extraordinary site.

From the NYT: “The train arrived at Menlo Park at 5:31. Darkness had settled down upon the bleak and uninviting place which Mr. Edison had chosen for his home, but the plank walk from the station to the laboratory was brilliantly lighted by a double row of electric lamps, which cast a soft and mellow light on all sides.

“The incandescent horseshoes gave out a yellow light which shone steadily and without the least painful glare and were beautiful to look upon.”

While this was not intentionally a Christmas lighting display, the arriving investors, in the holiday spirit, remarked upon the appropriate warmth and charm of the lights on the chilly December evening.

The light bulb would change the world but it would also make Edison a lot of money.

Soon Edison began aggressively promoting the various ways that electric lighting could be used to improve life – the more reasons, the more likely other investors would sign on and the more likely cities would hire Edison to install electrical power stations.

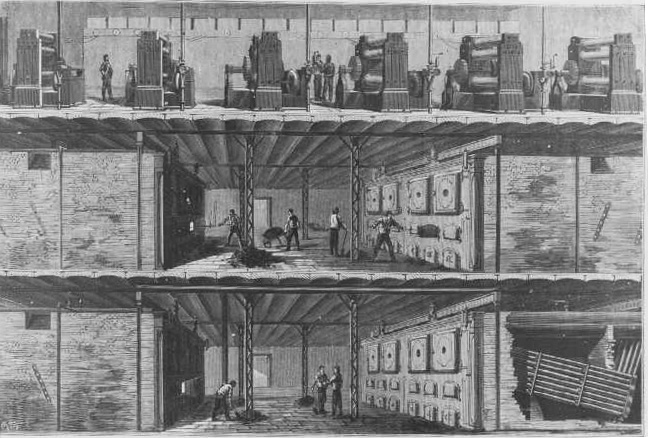

That is precisely what happened in New York on Sept 4, 1882, with the first commercial power plant in the world began operation in lower Manhattan on Pearl Street.

For the first time, the homes and offices of lower Manhattan would be able to light their interiors more pleasantly and conveniently than those homes with gaslight.

Whereas as the illuminations from gas would often create a sickly glow, the light from an electric glass bulb would seem romantic and alluring in comparison. Finally the candle had some competition.

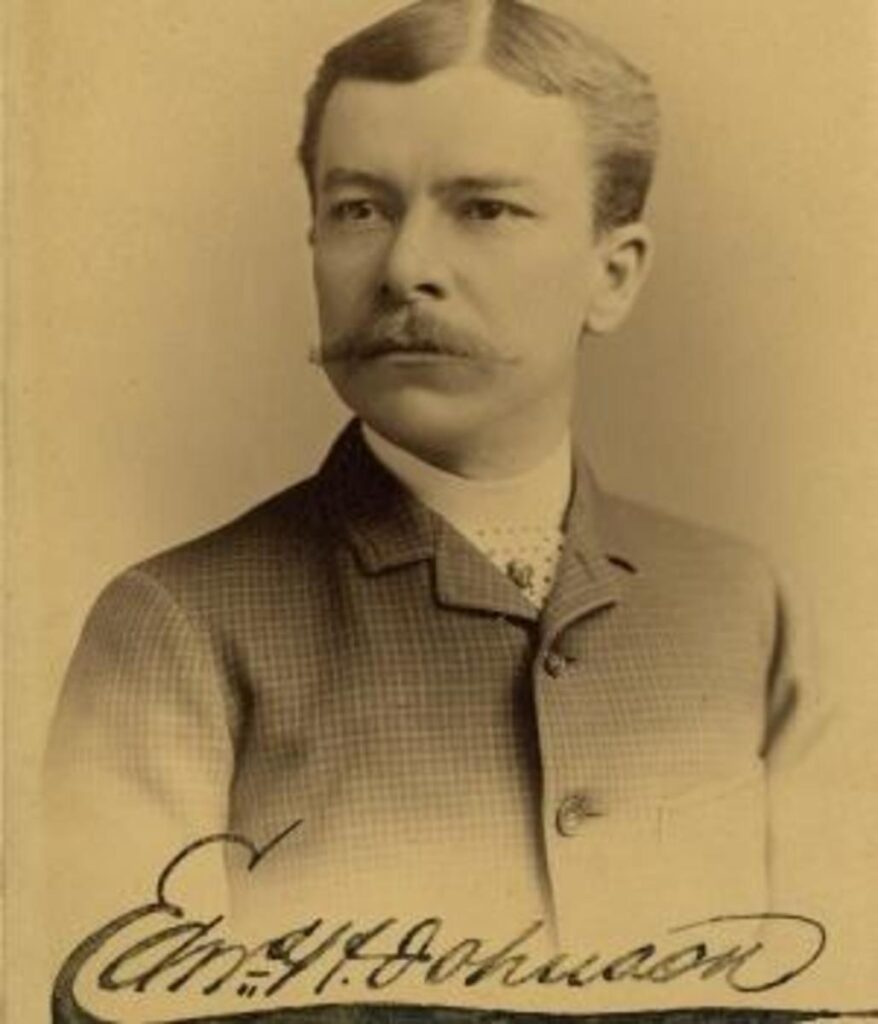

Further uptown, at the home of Edison’s friend and the vice president of the Edison Electric Company Edward Hibberd Johnson (pictured above), electricity was taking the place of a rather hazardous form of decoration.

For Johnson’s electric-tree idea took his inspiration from traditional candle-lit trees.

In the early 19th century a Christmas tree was considered a luxury of the urban rich who could afford to have a tree cut down for them and installed in their homes. But by the 1850s people could purchase trees at the market and carry them home to decorate for the season.

The most beautiful trees — the ones that seemed to fully embody the spirit of the season — were decorated with lit candles.

Getting a candle to stick in a tree was not easy. Some held the melted wax to branches, others pierced the candle with needles, tying them to the tree that way.

In 1878 an inventor named Frederick Artz devised a spring clip that could hold candles to the branches.

Now a family could attach lit candles to a Christmas tree and know — with just a touch more assurance — that the waxen dagger would not fall into the branches and burn the house down.

Keep in mind that in the 19th century Christmas trees were only installed in homes for only a few days. People did not lavishly decorate a month and a half before like we do today.

And trees were more closely monitored then. Next to the presents underneath the tree was a bucket of water.

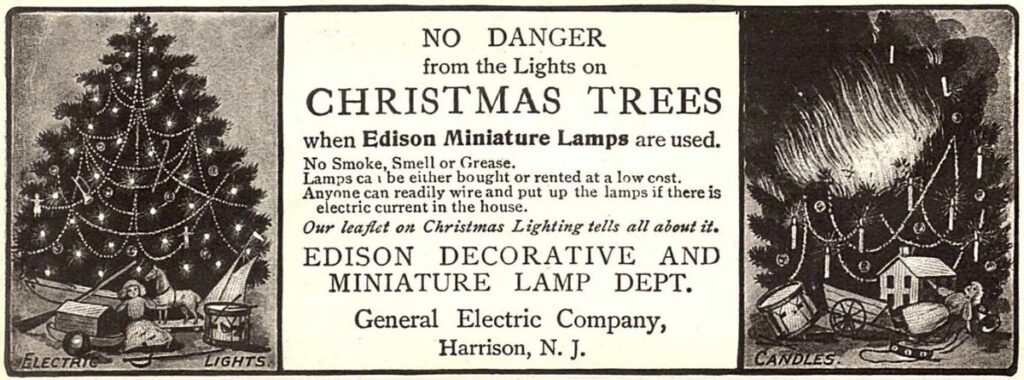

By 1908, some insurance companies refused to cover fires started by candle accidents on Christmas trees, claiming they were a clear and knowing risk.

So you can understand why people absolutely lit up at the idea of a Christmas tree with electric lights.

In January 1883, the journal Electrical World called Johnson’s tree on Madison Avenue the handsomest tree in the United States.

Pictures would suggest otherwise, although photographic process of the early 1880s were hardly equipt to capture such a unique and peculiar things – a rotating, brilliantly and colorful lit object of natural art.

But of course it wasn’t art. It was promotion.

With each year, Johnson would continue to let in the press into his home to report his unusual holiday marvel.

In addition he would install similar trees in places where Edison electrical power would soon be made available.

For instance, for Christmas 1883, he put up a much larger display tree at the Foreign Exposition in Boston at Mechanics Hall in Boston’s Back Bay.

From a 1904 history of Edison lighting:

“At the Boston Foreign Fair, about 1,500 Edison lamps were employed and the Christmas tree took several hundred more.

“This tree was deisgned to be operated by an automatic device which would make the light of the lamps appear and disappear in time with whatever music might be played and it was manipulated by means of a keyboard of switches, the operator being concealed at the base of the tree.

“The effect was so pleasing that Christine Nilsson, the Swedish Nightingale, who was in the audience begged to be allowed to manipulate it.”

All these wondrous, grandious displays were all for the general promotion of electrical power and not for the production of Christmas home decorating products themselves.

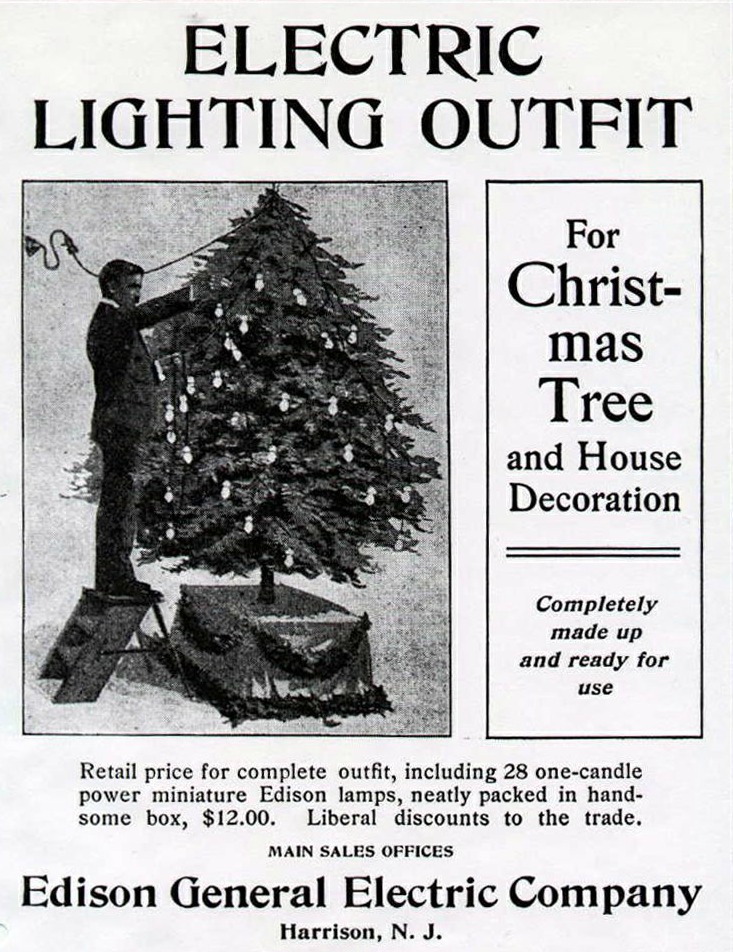

For at least two decades after Johnson’s extraordinary display, electric Christmas sets for the home were sheer novelty and clearly for the richest participants of the Gilded Age, those who could afford electricians and personal generators.

Consumers wouldn’t get to affordably light their home Christmas trees until the 20th century. Well, affordably can be debated.

In 1903, General Electric would finally make strings or festoons of miniature incadesent lamps – with bulbs of all colors — available for home holiday decorating. 24 bulbs for just $12! In 1903 dollars. That’s about $325 dollars today.

To decorate a tree of any meaningful size would require holiday revelers take a small mortgage out on their house.

But of course, by this time, Christmas in America was already being defined by thresholds of wealth. Christmas meant spending.

So for some, spending a week’s paycheck on Christmas lights might have been worth the heartache.

For some of course, it made more sense to RENT Christmas lights, a popular option in the year 1900.

From a General Electric Ad that year: “Edison Miniature Lamps for Christmas Treets. No Danger, Smoke or Smell. Lamps either rented or sold. Full directions furnished, enabling anyone to readily wire and put up the lamps.”

4 replies on “The story of the world’s first Christmas tree with electric lights”

Ha ha ha… “no danger” my arse! Old, and even many recent, incandescent lights burn hot and the wires get abused and have caused many a fire. This was a great article, though. Very informative and puts me in the mood for holiday decorating.

My thoughts as well, but I guess compared to candles, it was “safe”. If incandescents are such a hazars (as it so seems now, compared to modern LED’s), I don’t know how they ever pulled off using candles! (Even with a bucket of water sitting by).

I am amazed that the first tree rotated. I have been using one for years thinking when I found it that it was a new thing. Silly me!

Very interesting story. In the late 1920s, my mother’s family living in Asheville, North Carolina USA were the first in their neighborhood to use electric lights on their Christmas tree. My mother said that it was such a new and amazing site to see.