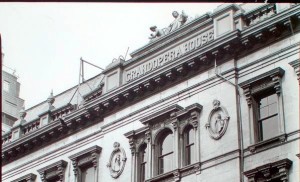

In last Friday’s podcast on the Hotel Chelsea, I mentioned a building that was located very near by called the Grand Opera House, at the northwest corner of 23rd Street and 8th Avenue. Here it is:

The opera house sprang up in 1868, the project of Samuel N. Pike, who purchased the land directly from Chelsea estate owner Clement Clarke Moore himself. In fact, the original Moore estate was only a block away.

The Pike Opera House, as it was called in those days, was Pike’s play for legitimacy in New York. A German immigrant who arrived in the U.S. in 1837, Pike lived in New York for a few years and made his fortunes in wine imports. Aspiring to upper-crust tastes, Pike fell in love with opera music after viewing performances by PT Barnum chanteuse Jenny Lind.

Pike constructed a massive opera house in his adopted home of Cincinnati in 1859 and many years later built a companion here in Manhattan at 23rd Street. Pike’s timing was off; theaters would crowd along 23rd Street in the coming years, but in 1860s, the wealthy preferred the Academy of Music down on 14th Street.

So the next year, Pike sold his lavish hall to two rather unlikely investors — Jim Fisk and Jay Gould, grade-A robber barons, pals of Boss Tweed and the orchestrators of the Black Friday Panic of 1869. Why would these two nefarious characters want an opera house?

The house’s upper floors doubled as the offices of their own Erie Railway venture. Fisk’s mistress Josie Mansfield was frequently installed into productions at the newly named Grand Opera House; it was even rumoured her next-door apartment was connected to the opera house with an underground tunnel.

However it does seem that Fisk and Gould were legitimately aficionados of the theater, or at very least fans of the elite who would attend them, and the profits that would follow. The Grand Opera House would soon showcase a great number of theater endeavors outside of opera.

Mansfield would prove Fisk’s downfall; her other lover Edward Stokes shot him in 1872. Mourners could stream through the lobby of the Opera House and observe Fisk’s body laying in state there. Gould would operate the Opera House for several years afterwards, eventually renting it out to vaudeville shows and ‘second-run’ Broadway productions, its fortunes disintegrating as theater moved uptown and the Chelsea neighborhood became more middle-class.

Like many old stages before it, the Grand Opera House switched to films in the 1920s. RKO tried its best to rehabilitate the space, hiring Thomas Lamb to renovate the theater with modern flourishes, reopening the space as the RKO 23rd Street Theatre. The picture below is actually from the year before the renovation, which stripped away some of the the Grand Opera’s frippery:

The site remained a movie house through the 40s and 50s, finally closing on June 15, 1960. In a further indignity, the Opera House was thoroughly gutted in a fire (seen in the picture below (courtesy Cinema Treasures):

And thus it was time — to put in a strip mall! Today you can visit that very corner and enjoy a rather enduring Chicken Delight location or stop and have a Texas-sized margarita at the corner Dallas Barbecue.

3 replies on “Chelsea’s old Opera House: from robber barons to BBQ”

Nice blog. Enjoyed going through it. Keep it up the good work. Cheers 🙂

It seems we lose a little bit of elegance each time one of these grand structures are repurposed for something ordinary.

That stretch of Chelsea was the original theatre district and there are still theatres tucked away in some of the older buildings that house off off broadway plays and events.

The silent film industry originally sprung up in the vicinity and to this day there are still many storefronts catering to professional photographers and film companies in the area.