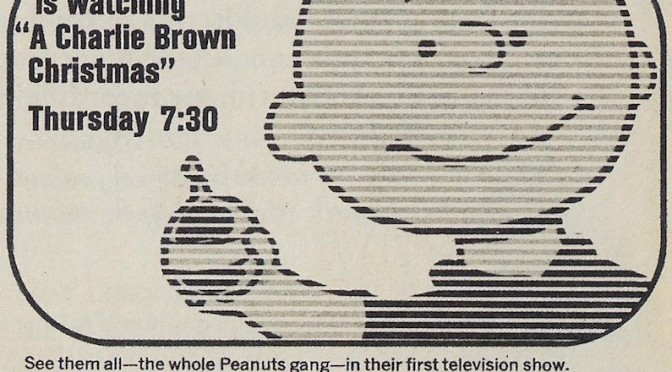

The first time: A TV Guide advertisement from 1965 announcing the upcoming Charlie Brown special, “presented … by the people in your town who bottle Coca-Cola.” [source]

A Charlie Brown Christmas, the holiday special to end all holiday specials, needed a little encouragement from the Madison Avenue advertising world in 1965 to spring into existence. Â In fact, Peanuts’ creator Charles Schulz wasn’t exactly clamoring for any kind of television version of his classic characters.

The Minnesota cartoonist’s first fateful encounter in New York came in June 1950, when he met with editors at United Feature Syndicate, located in the Daily News Building on 42nd Street, to form the strip which eventually became Peanuts. Â The syndicate initially restricted the size of Schultz’s cartoon panels to flexibly adhere to the various column sizes of their partner newspapers. This forced simplicity into Schultz eventual designs for his characters — the bulbous head of Charlie Brown, the dash of black ears on an all-white beagle.

The syndicate unveiled Schulz’s creation a few months later, on October 2, 1950. Within a decade, it would be one of America’s most famous comic strips.

Flash-forward to another spring in New York, April 1965, and to the bustling offices of advertising agency McCann Erickson, at 485 Lexington Avenue. Â They were Madison Avenue’s most successful agency and held among their clients the defining product of post-war America — Coca-Cola.

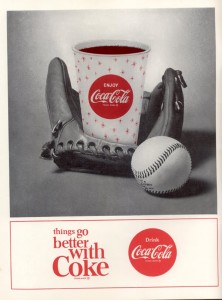

McCann Erickson would be responsible for some of Coke’s most recognizable advertising campaigns during a decade when the beverage would reach international popularity.  In 1971, agency efforts would underscore Coke’s world domination with ‘I’d Like To Buy The World A Coke’.  At left: A McCann-Erickson Coke ad from 1965, courtesy the blog Beautiful Life

Coke was looking for a television show to sponsor for the holiday season of 1965, one that could be developed from scratch, with a Coca-Cola audience in mind — namely, families with children.

(If you’re a ‘Mad Men‘ fan, you may also be familiar with McCann Erickson as the agency from Season 3 who bought out Sterling Cooper, forcing Don Draper and the gang to quit and form a new, fledgling agency. The events of Season 4 — with Ken Cosgrove still in McCann’s employ — play out during 1965, the same year as AÂ Charlie Brown Christmas.)

One of McCann Erickson’s lead executives John Allen had an idea in mind. Â He had seen a documentary on Schulz, called A Boy Named Charlie Brown, and that film contained some crudely animated versions of Charlie Brown and Lucy by animator Bill Melendez. Â Allen called up Melendez and asked if Schulz had ever been interested in developing a full-length television special.

He had not, actually. Â In fact he had turned down many previous offers to produce animated specials. Schulz said at the time, “There are some greater things in the world than TV animated cartoons.” Â Yet, perhaps contradictory to this, Schulz seemed open to licensing and merchandising opportunities. Â In 1960, Charlie Brown and Lucy made their first animated appearance on television hawking cars for Ford:

But you couldn’t turn down an offer by the world’s biggest sugary beverage, could you? Â Melendez agreed, brought the offer to Schulz at his northern California home, and from his studio there, he and a team of animators frantically put together a program in time for the holidays.

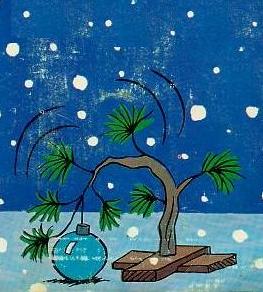

Schulz wanted lots of snow and ice skating and talk of “the true meaning of Christmas,” inspiring the special’s lengthy Biblical monologue by Linus. Â They auditioned Hollywood children and kids from Schulz’s neighborhood for the voiceovers and called up San Francisco-based musician Vince Guaraldi, who had recently cracked the Billboard charts with the song ‘Cast Your Fate To The Wind‘, to score the special.

Below: Snoopy careens around the Rockefeller Center ice skating rink in the 1969 film A Boy Named Charlie Brown.

The half-hour feature was finished just a few days before broadcast. TV Guide and newspapers were already advertising the airing when Melendez sped to CBS’s brand new corporate offices at 51 West 52nd Street; the Eero Saarinen-designed building was nicknamed Black Rock for its monolithic design. (Pictured below, pic courtesy Skyscraper.org.)

Melendez screened the special for executives who were greatly underwhelmed with the final product. Â “It seems a little flat … a little slow,” said one executive, assuring Melendez that CBS would not be ordering any future Peanuts specials. Â According to producer Lee Mendelson, “If the show hadn’t already been scheduled to air in six days, it might never have been broadcast.”

Melendez screened the special for executives who were greatly underwhelmed with the final product. Â “It seems a little flat … a little slow,” said one executive, assuring Melendez that CBS would not be ordering any future Peanuts specials. Â According to producer Lee Mendelson, “If the show hadn’t already been scheduled to air in six days, it might never have been broadcast.”

Fortunately, a Time Magazine reviewer was allowed to screen A Charlie Brown Christmas and wrote a rave review that ran a couple days before showtime. From the review: “For one thing, the program is unpretentious; for another, it is unprolonged (30 minutes).”

But television audiences would have the final say and, upon broadcast on Thursday, December 9, it became the week’s second biggest show behind Bonanza.  Popular acclaim was soon joined by critical plaudits; a few months later, Schulz, Melendez and Mendelson arrived back in New York to receive an Emmy Award for Best Animated Special.

The original version of A Charlie Brown Christmas included a short shot of Linus being flung by Snoopy into a Coca-Cola sign. It was later edited to say Danger, which was then edited out entirely, because, well, it’s a bit disturbing. (See below.) Â No remnant exists today within A Charlie Brown Christmas of its Coca-Cola advertising reason for being.

Four years later, Charlie Brown, Snoopy and Linus would head to New York themselves, in the 1969 feature length film A Boy Named Charlie Brown (title similar to the 1962 documentary) in which Charlie would nervously compete in the Scripps Spelling Bee competition.

Schulz’s Manhattan is as abstract as any of his landscapes, but he does depict both the New York Public Library and Rockefeller Center. Â It’s here that Snoopy reprises his ice skating routine to the music of Guaraldi.

There’s also several scenes of a cracked-out Linus stumbling through the city at night, looking for his blanket, which he has unwisely loaned to Charlie. An excerpt of the film:

A Boy Named Charlie Brown made its premiere at Radio City Music Hall on December 11, 1969. You can check out the original film program here.

3 replies on “Good grief! Madison Avenue’s connection to ‘A Charlie Brown Christmas’”

Thre was a story on NPR last year, that went into the tale of the Charlie Brown Christmas and CBS. As I recall, the jazz soundtrack scared CBS into thinking the music was too depressing for the holiday season and would only be of interest to an African American audience. Obviously they were wrong.

Kevin

Never miss a Chuck Brown Christmas (or Its a Great Pumpkin) and I am 58! In both of these programs Charlie Brown is always referred to by the other characters as ‘Charlie Brown”. That is except in one of those two programs when one of the characters refers to him only as Charlie and not with the Brown added to it. Yeah I guess I have too much time on my hands or know worthless trival stuff! Hsppy, safe holidays to all in NYC and elsewhere

Looks like they took down the missing scene, lest we see something we shouldn’t.