This month America celebrates the 100th anniversary of the National Park Service, the organization which protects the great natural and historical treasures of the United States. There are a number of NPS locations in the five borough areas. Throughout the next few weeks, we will focus on a few of our favorites.  For more information, you can visit National Parks Centennial for a complete list of parks and monuments throughout the country.  For more blog posts in this series, click here.

The following also features an excerpt from the Bowery Boys Adventures In Old New York, now available for sale wherever books are sold and online at Amazon or Barnes and Noble.

A vivid display inside the visitor center at 290 Broadway.

AFRICAN BURIAL GROUNDÂ NATIONAL MONUMENT

DUANEÂ STREET, CIVIC CENTER, MANHATTAN

The African Burial Ground, tucked right into the heart of Lower Manhattan, two blocks north of City Hall, represents one of the greatest archaeological finds and saddest stories in New York’s history. The somber monument, opened in 2007, gives long overdue respect and honor to the remains buried here of New York’s first African and West Indian communities.

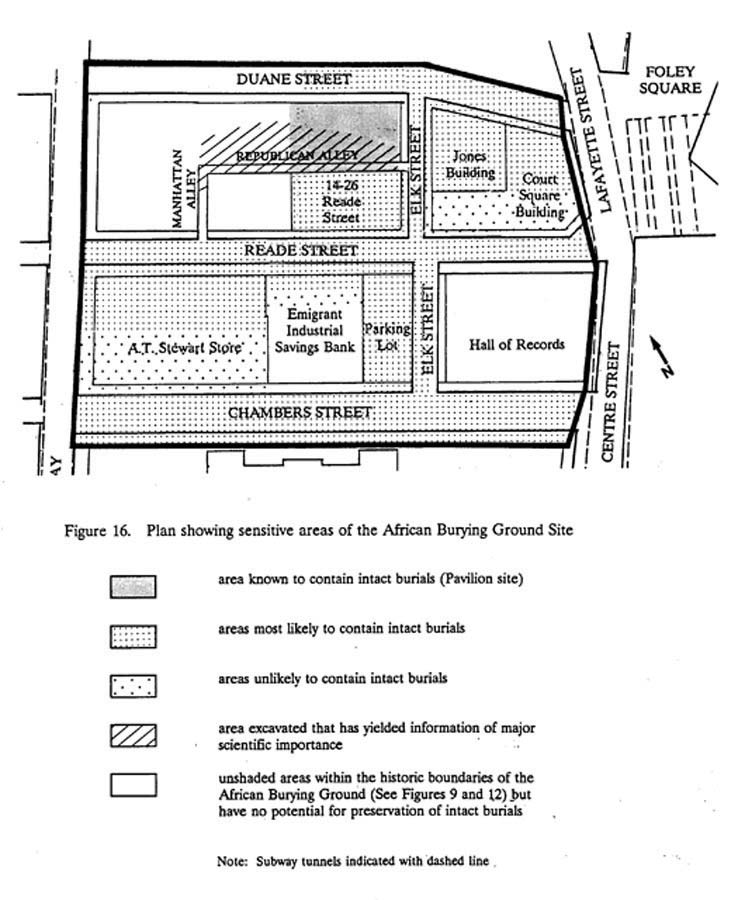

In fact, the African Burial Ground is far larger than the site of today’s monument. Its true size is unknown, although it is believed to cover about seven acres, stretching out under many of the surrounding buildings, including those in Foley Square and along Chambers Street.

The burial ground dates back to the seventeenth century, when New Amsterdam was a company town for the thriving Dutch West India Company, and the town’s early settlers were primarily traders, not builders or town planners. In their eyes, they didn’t sail all the way across the Atlantic from Holland to do menial work.

And so in 1626, to stimulate and facilitate the colony’s growth, the Dutch imported the New World’s first African slaves, a group of eleven people. Early records show that they were assigned names associated with their homelands or original captors: Antony Congo, Dorothe Angola, Jan Negro. Slave labor would be used to build many of New Amsterdam’s major structures, including the large wall that lined the northern edge of town.

One of the most notorious landmarks of the slave trade sat at the corner of Wall and Water Streets (once the shoreline, back in British New York). The Meal Market was established in 1711 not only for the buying and selling of raw products like grains, but also for the purchase and leasing of “negroes and Indian slaves.â€

It’s interesting to note that under the Dutch, enslaved men and women could earn their freedom and eventually own property. But those who did gain independence were not permitted to reside within the city’s walls. Instead, they were forced out beyond the borders to settle in the “free Negro lots†found around the southern edge of Collect Pond.

Things got worse for the colony’s slave population in 1664, when the British took control and renamed the colony New York.

They brought with them their own stricter slavery traditions and stripped away those meager legal protections that had been afforded by the Dutch. New York was not a plantation town; many families owned one or two slaves and they were usually kept in or near their homes. By the 1740s thousands of enslaved men and women from Africa and the Caribbean lived in New York, more than one-fifth of the city’s population.

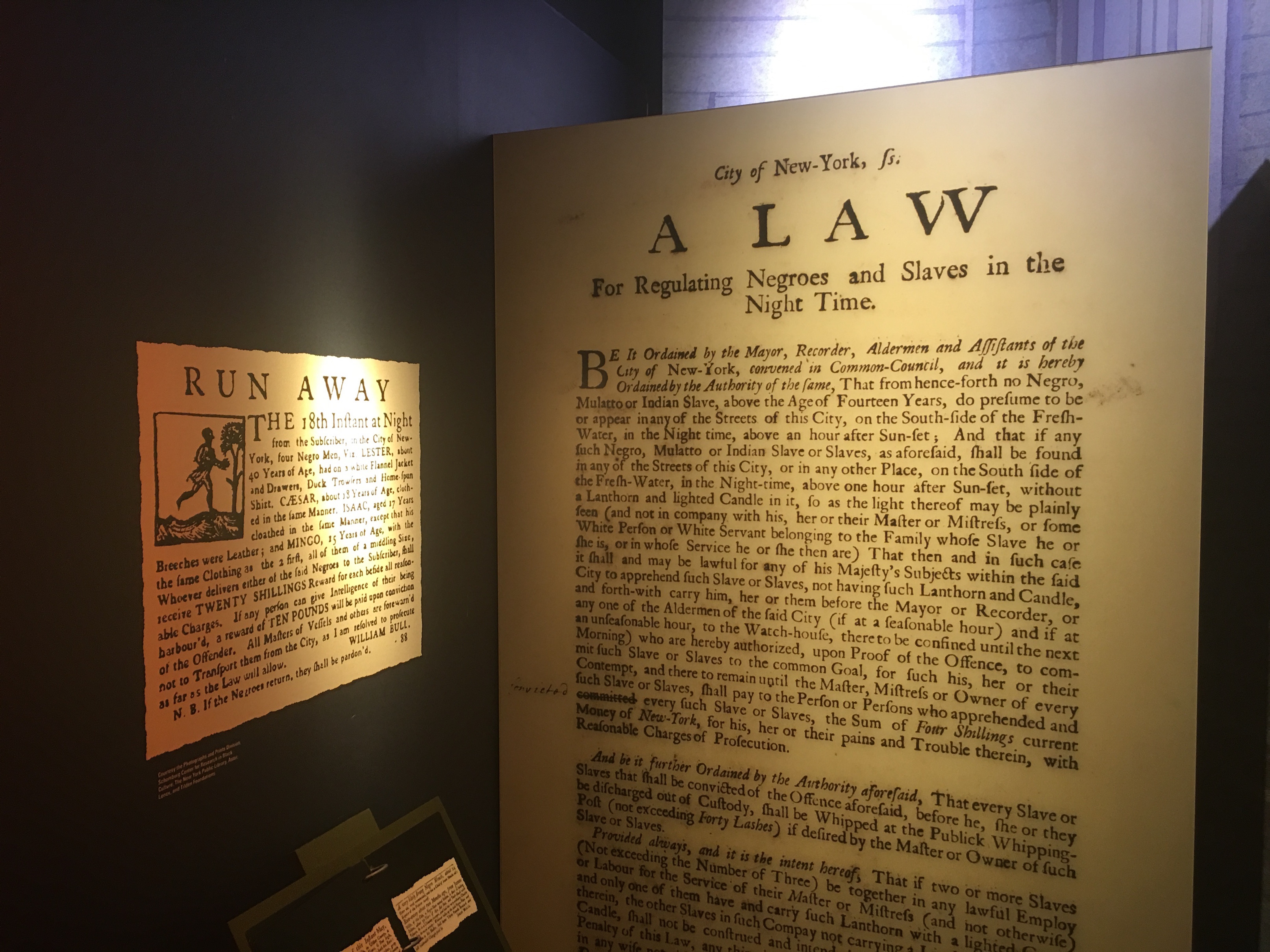

The visitor center serves as a museum about slavery and an exhibit to the early black experience in New York

While a diverse number of religions were practiced under English rule, most black New Yorkers eventually converted to the Anglican Church. But Trinity Church did not allow the remains of black people, slave or free, to be buried in its churchyard. And so this population was forced outside the city walls again, this time claiming some land south of Collect Pond as their own private burial ground.

In their burial ceremonies and mourning practices, the city’s African and Caribbean residents were able to display their original religious beliefs, and could come here and bury friends and loved ones according to traditional burial customs.

The remains of 419 individuals are contained in mounds outside next to the monument.

In the early years, at dusk, New Yorkers would hear the foreign-sounding music, drum beats, and the sounds of exotic ceremonies drifting down from the burial yard.

Well, that was simply too frightening for some white New Yorkers, and so, starting in 1722, it became illegal for blacks to congregate at night, and a 1731 law prohibited more than twelve people from gathering during the day at the burial ground. These draconian laws against black New Yorkers were instigated due to the events of April 1712, when a group of slaves conspired to burn the city. Twenty-one enslaved and freedmen were put to death in retaliation.

While these laws put a damper on many religious ceremonies, it was still possible to show some freedom of expression in the burials themselves. The dead were buried in wooden boxes, most facing east, as was customary for some African religions, and trinkets of religious or personal value (cowrie shells, pipes, buttons, and pieces of coral and crystal) were placed inside the coffins with the deceased.

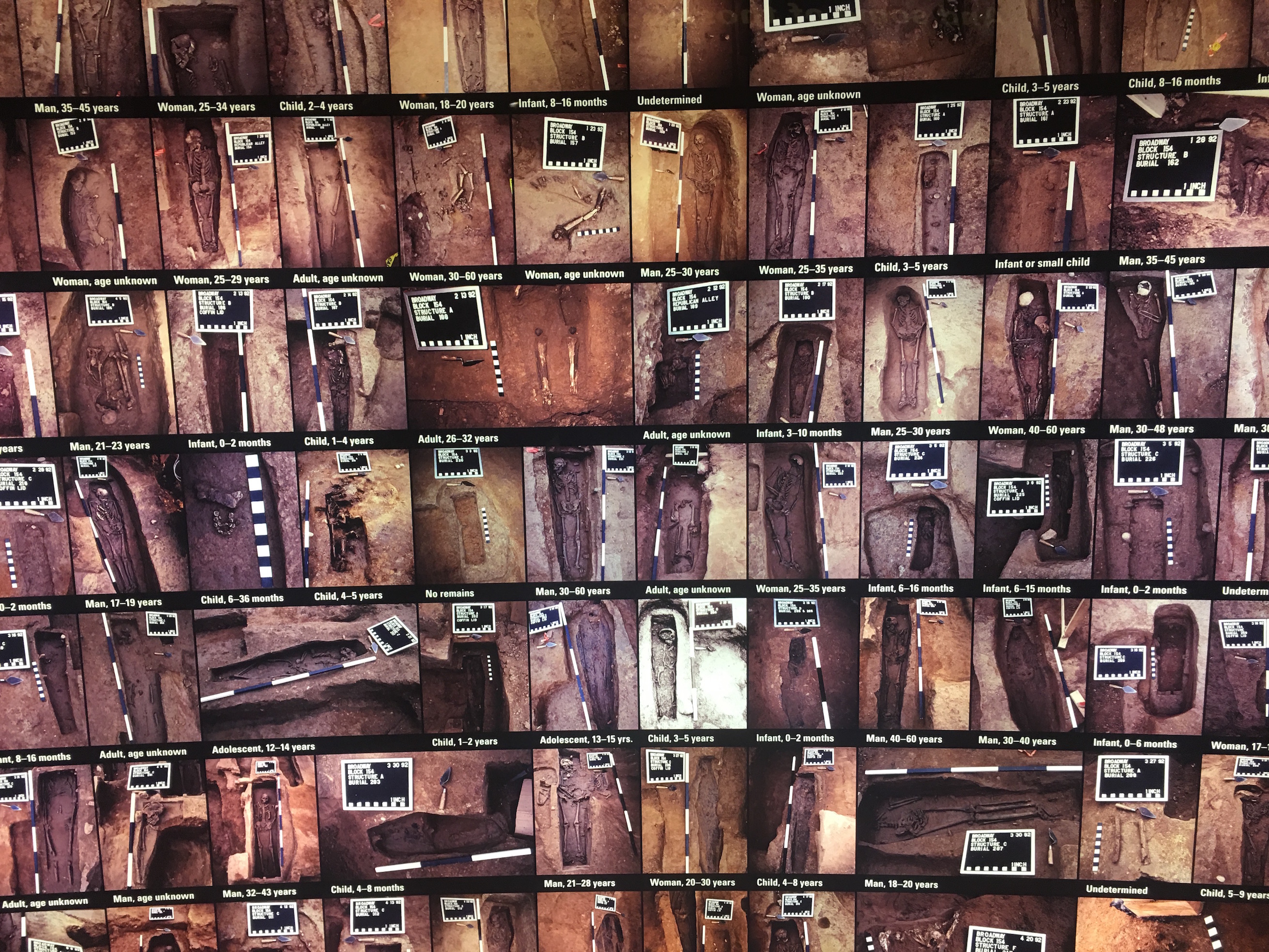

Images of the remains found on the site of the very building you’re standing in are displayed inside the visitors center.

With the departure of the British in 1783 and the beginning of the city’s great march northward, this land quickly became much more valuable. By the early 1810s, Collect Pond and its now-spoiled natural surroundings were simply filled in, the marshes drained, the hills leveled.

The graves of many of New York’s early slave and free black population, the resting place of approximately 15,000 bodies here, were covered over in landfill, in some places 16 to 25 feet deep.

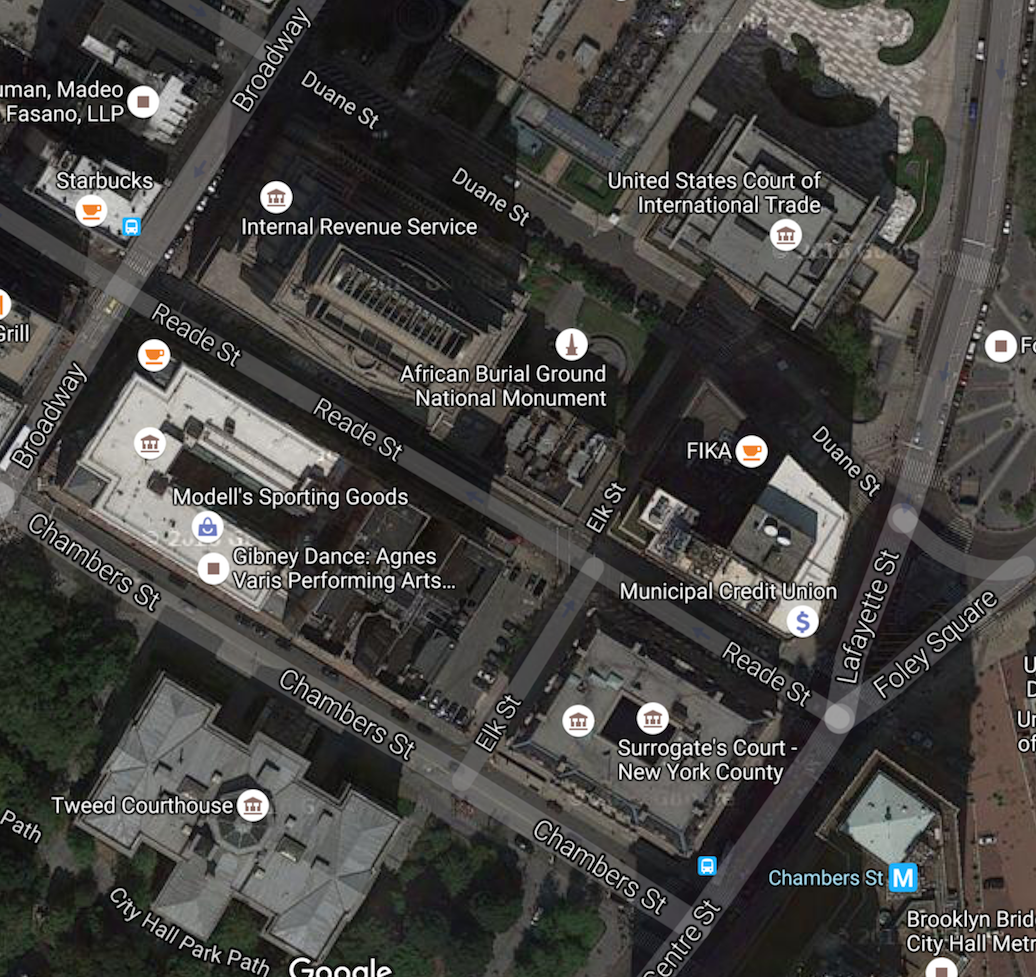

Map of the site and the projected location of other burials. Below is a current Google Map satellite view of the site:

The early structures built atop the burial ground were not very tall, none more than a few stories high. As a result, the depths of their foundations were no deeper than 20 feet or so. In some places, the burial ground lay below the newly erected buildings, completely preserved by the landfill that had been hastily thrown over it.

Flash forward—way forward—to 1991, when New York City was home to hundreds of skyscrapers, but unbelievably this small seven-acre area still only held structures of modest height. When work began on a nearby government building at 290 Broadway, excavators happened upon the first evidence of human remains. Throughout the next year, excavations would uncover a total of 419 bodies, along with a wide assortment of artifacts.

The monument to this discovery, completed in 2007 and operated by the National Park Service, returns a bit of grace and reverence to this site, and focuses on the spiritual beliefs of those who were interred here centuries ago. Immediately to your right is a set of seven evenly and elevated spaced beds of grass, where the bodies of the 419 have once again been buried, collected in hand-carved wooden sarcophagi.

The following words are inscribed upon the monument (Duane Street, between Broadway and Lafayette Street. Visitors’ center at 290 Broadway):

For all those who were lost

For all those who were stolen

For all those who were left behind

For all those who are not forgotten

WANT MORE INFORMATION? Visit the NPS African Burial Ground National Monument site for more information.

LISTEN TO OUR PODCAST! We have an entire show on the African Burial Ground. It’s Episode #115. You can find it on iTunes or download it from here.