This month America celebrates the 100th anniversary of the National Park Service, the organization which protects the great natural and historical treasures of the United States. There are a number of NPS locations in the five borough areas. Throughout the next few weeks, we will focus on a few of our favorites.  For more information, you can visit National Parks Centennial for a complete list of parks and monuments throughout the country.Â

The following is also an excerpt from the Bowery Boys Adventures In Old New York, now available for sale wherever books are sold and online at Amazon or Barnes and Noble.

CASTLE CLINTON

MANHATTAN. BATTERY PARK

Tourists looking to purchase tickets to the Statue of Liberty and Ellis Island (also two landmarks that are maintained by the NPS) enter an old circular stone structure in Battery Park called Castle Clinton. Ticket selling is by far the least exciting job in the fort’s history, a rather banal function for a building that traces its origins to the founding of the United States.

Back in 1783, fresh from the victories of the Revolutionary War, New Yorkers gathered around the docks on November 25 to forever wave off the British from New York Harbor. When it was soon discovered that one last British flag remained hanging from a greased flagpole—a final goodbye prank, as it were—jaunty patriots shimmied up to remove it. This event would soon become the driving force of New York’s annual Evacuation Day celebrations, a symbolic marker of the end of British rule. (If we could come up with a method to safely secure drunk revelers as they climbed greased flagpoles today, then we’d say let’s bring it back!)

But the threat of an unwelcome British return lingered on. In 1790, the city dismantled Fort George (the dilapidated fort built by the Dutch), and the cannons that gave the Battery its name were removed and replaced with a strolling promenade. But less than two decades later, new saber rattling by British forces so unnerved New Yorkers that they built new, stronger forts at locations scattered throughout the harbor. Some of them—like Fort Wadsworth on Staten Island and Castle Williams on Governors Island (another NPS property) —still stand today.

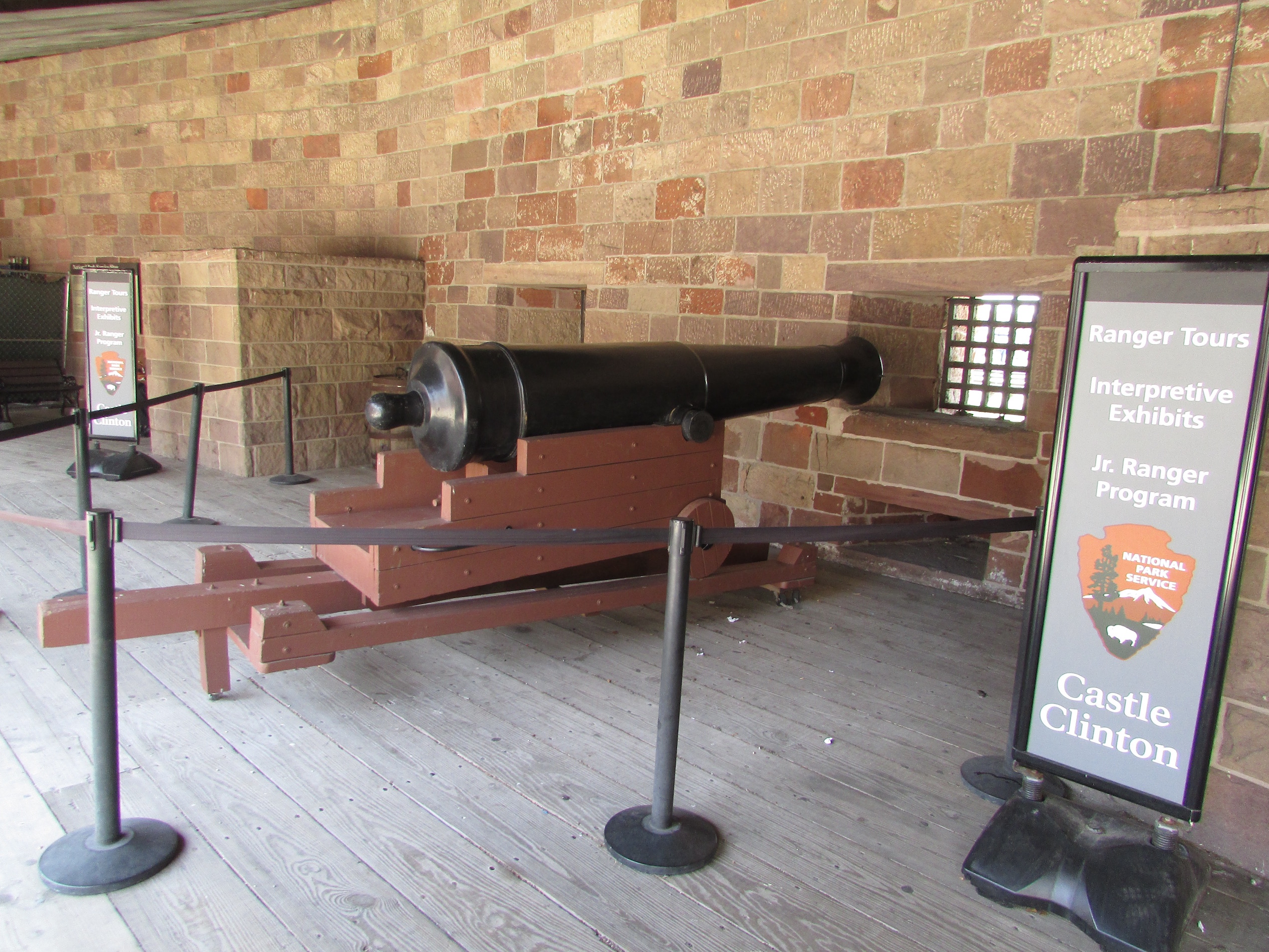

A modest museum inside Castle Clinton features three interesting models of how the structure used to look and how it related to the land around it.

But none has had the inconceivable adventures of West Battery, completed in 1811 as an island fort, located 300 feet from shore and connected to the mainland by a long bridge. Its thick stone walls could withstand a vicious attack, and its 28 guns aimed into the harbor would surely beat back any aggressors. It was later renamed Castle Clinton, after New York’s governor (and former mayor) DeWitt Clinton, a hopeful name, given Clinton’s own political tenacity and endurance.

But while the War of 1812 would come to American shores, it never arrived in New York Harbor. After serving some minor military purposes, Castle Clinton was eventually sold by the federal government to the city in 1823. And it was then that things got decidedly more festive for the old fort.

During an excavation in 2006, portions of the old Battery Wall were discovered. Â They are displayed within Castle Clinton today.

First it was transformed into an entertainment palace, rechristened Castle Garden, and greatly expanded, with a spacious second floor and an ornate fountain at its center. Still accessed by a narrow bridge, the experience was magical and otherworldly for visitors, its gaslight illuminations dancing above the waves.

Castle Garden was a ballroom, concert venue, lecture space, and even beer hall. In 1824, the Marquis de Lafayette, the most exotic still-living embodiment of the Revolutionary era, was feted here by grateful New Yorkers. In 1842 Samuel Morse demonstrated a new gadget that would change the world—the telegraph. (A line was strung between here and Castle Williams; its first message was, rather dramatically, “What hath God wrought?†And they hadn’t even seen their phone bill yet!) For a short time, you could even enjoy luxurious saltwater baths out on the Battery promenade.

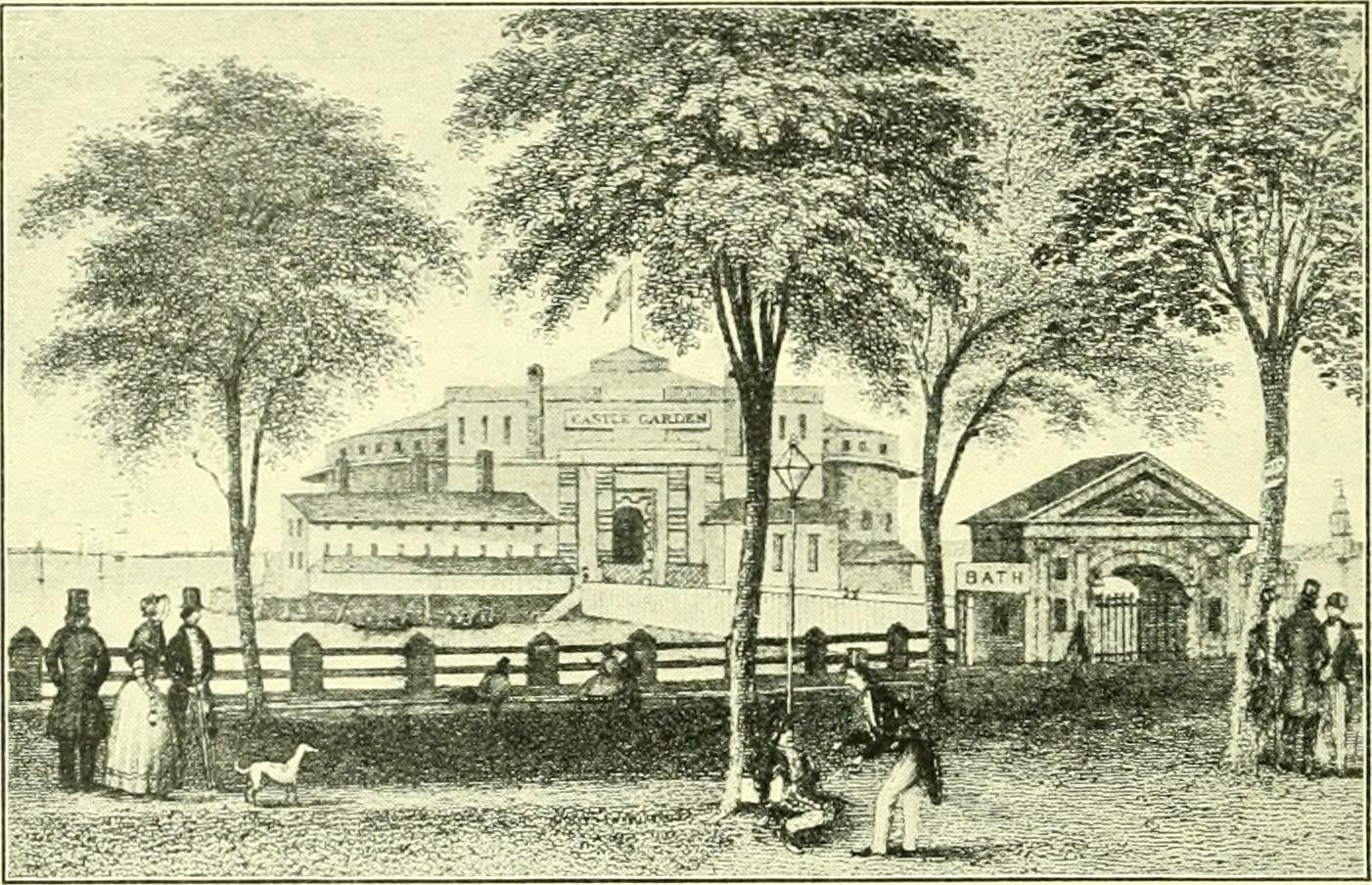

But the most famous evenings at Castle Garden (pictured above in 1850) belonged to the Swedish opera singer Jenny Lind. Extensively hyped by impresario P. T. Barnum, the so-called Swedish nightingale brought New York music lovers to tears here on September 11 and 13, 1850, perhaps the most legendary concert nights in American history (pre–stadium seating, that is). “Jenny Lind has already won a hold on the sympathies of the American public, such as no other vocalist ever obtained,†cooed the New York Daily Tribune. “The audience for which she sang was the greatest ever assembled at a concert in this city.â€

Just five years later, in 1855, Castle Garden would see thousands more foreign imports, albeit less enthusiastically proclaimed. For it was then that the old fort-turned-amusement venue became New York’s first immigration depot, a desperately needed transformation, coming as a tidal wave of European immigrants vexed the ports.

Newly arrived Irish and German immigrants during the 1840s and early ’50s had been taken advantage of by greedy “runners,†unscrupulous characters who led them into scams or false promises of housing and employment, often leaving them with neither (and empty pockets).

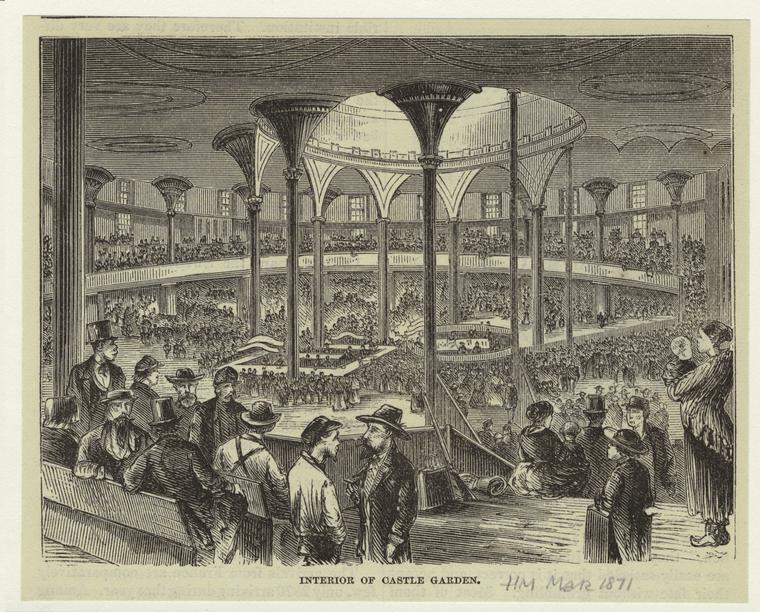

The interior of Castle Garden during its period as an immigration station.

Castle Garden, as an immigration depot, registered the new arrivals and provided vital connections with immigrant aid societies. It would be a proto–Ellis Island, processing more than 8 million people upon their arrival to America. Most likely some of you reading this have ancestors who passed through the halls of Castle Garden.

Castle Garden as an immigration station, 1861, the former battery swarming with activity. Millions of immigrants arriving in New York passed through this depot.

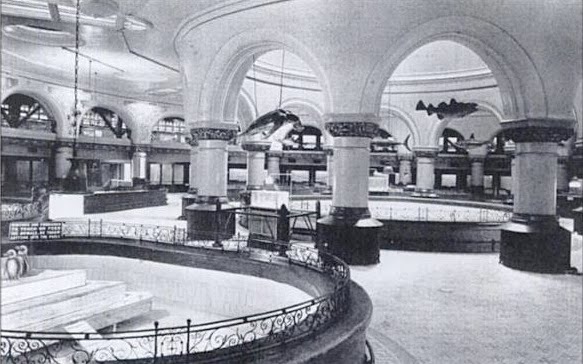

Another model within Castle Clinton features the landscape as it looks during the period the structure housed the New  York Aquarium.

By 1890 the federal government finally got involved with immigration processing and built a new processing center upon a little island in New York Harbor, long ago owned by Samuel Ellis. This switch freed Castle Garden to occupy itself with some other residents—this time of the underwater variety.

After a redesign by the renowned architectural firm of McKim, Mead, and White, the New York Aquarium would open here in 1896, its former concert hall and processing desks replaced with the latest aquatic technology of the day. By this time, of course, landfill had joined the structure to the mainland. Families could now gallivant through Battery Park and into the front gates to explore a maze of open pools and glass exhibition tanks, filled with a variety of creatures that (more often than not) did not survive the changing of seasons.

Today there are no aquatic creatures of any variety. However there are plenty of tourists from all over the world, lined up to get their boat tickets to the Statue of Liberty and Ellis Island.

They were a surprising yet appropriate pairing, the old fort and a bunch of tropical fish, replete with harbor waves crashing nearby. Unfortunately, Parks Commissioner Robert Moses was not a fan and decreed that the retrofitted old fort had finally performed her last number. In 1941, Moses used the construction of the Brooklyn–Battery Tunnel as an excuse to move the popular aquarium to Coney Island, snarling that “the Aquarium is an ugly wart on the main axis leading straight to the Statue of Liberty.†The fort should be destroyed entirely, he explained, for “its guns never fired a shot against an enemy.â€

Inside the New York Aquarium at Castle Garden:

His destructive urges were only partially rebuffed by the community. Most of the frill and finery—almost everything that had been added since 1823—was removed, leaving only the barren stone form of the original fort intact. And that’s exactly how it has remained ever since. Castle Clinton received National Monument status in 1975.

Today the old fort quietly allows New York’s showier landmarks their day in the sun. But we challenge you, Mr. Moses. There may never have been a shot fired from Castle Clinton, but these walls have seen more drama and have been more important to the American experience than almost any other American fort standing today.

WANT MORE INFORMATION? Visit the NPS Castle Clinton National Monument site for more information.

LISTEN TO OUR PODCAST! We have an entire show on Battery Park and Castle Clinton. It’s Episode #31. You can find it on iTunes at the Bowery Boys Archive, featuring our older shows. Â Or download it from here.