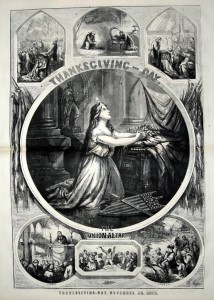

Above: A Thomas Nast illustration from Harper’s Weekly, November 1863, clearly putting the event in the context of war and hardship.

In practice, Thanksgiving celebrates the supposed feast between the Pilgrims and their Native American neighbors in Massachusetts. But meals of ‘thanksgiving’ have been part of the Western world customs for hundreds of years, and today the meal is more an excuse to gather the family together and count the seconds until holiday shopping.

Because that ‘original’ meal was only vaguely documented, let me give you a more definite event — 150 years ago, President Abraham Lincoln declared a national celebration of Thanksgiving for the last week in November:

“I do therefore invite my fellow-citizens in every part of the United States, and also those who are at sea and those who are sojourning in foreign lands, to set apart and observe the last Thursday of November next as a day of thanksgiving and praise to our beneficent Father who dwelleth in the heavens.”

Perhaps you did a double-take at that statement. There’s no mention of Pilgrims or Indians in Lincoln’s proclamation, which was made on October 3, 1863. There is, of course, several soothing religious references. (You can read the entire statement here.) After all, the United States had been fighting a Civil War for over two and a half years. Any words of peace and calm, paired with boasts of American bounty and expansion, would have put the bloody conflict in a divine context. “[H]armony has prevailed everywhere except in the theatre of military conflict,” Lincoln wrote.

Perhaps you did a double-take at that statement. There’s no mention of Pilgrims or Indians in Lincoln’s proclamation, which was made on October 3, 1863. There is, of course, several soothing religious references. (You can read the entire statement here.) After all, the United States had been fighting a Civil War for over two and a half years. Any words of peace and calm, paired with boasts of American bounty and expansion, would have put the bloody conflict in a divine context. “[H]armony has prevailed everywhere except in the theatre of military conflict,” Lincoln wrote.

At right: Thanksgiving dinner at ‘the Home for the Friendless’, 1860s. I cannot imagine a more grimly named institution! courtesy NYPL

New Yorkers had celebrated a form of Thanksgiving for many years prior to the 1863 proclamation. But the feast had always been considered a regional, New England celebration, one a little foreign for the city.

From The New York Sun, November 26, 1863: “The sights and scenes in our city yesterday afforded evident indications of a unanimous determination … to break up once and all the monopoly of Thanksgiving, so long enjoyed by the New Englanders. For years past, it had been a standing boast of the genuine ‘Down Easters’ that the air of New York was unsuited to the festival of the Pilgrim fathers.”

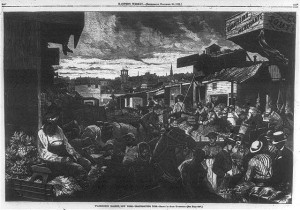

Below: Washington Market, always a hectic place, was especially so on Thanksgiving. This scene from Harper’s Weekly depicts frantic shoppers in 1872. Courtesy Library of Congress

Don’t tell New Yorkers what they can’t have! The Sun promised a “racy and peculiar” New York Thanksgiving that year. The markets were clogged with shoppers, as New Yorkers came out in force to purchase items for their own Thanksgiving meals. Every other man on the street seemed to have a naked bird flung over their shoulders. “Evidentally, every family man and woman, who could raise the number of greenbacks, invested them in Thanksgiving fixings.”

This might have been a little journalistic posturing. Just five months earlier, New York had been ablaze in the Draft Riots, several days of violence towards its own citizens, fueled by an unfair conscription policy and the fears and racial hatreds of its citizens. Most of the burned buildings had been cleared, but the bloodshed was on many minds. Many benefits throughout the city raised money for injured Union soldiers and the families of those who had died in battle.

The Sun quietly refers to the Draft Riots’ most sickening event, the burning of the Colored Orphan Asylum. “At the Five Points House of Industry the little ones are to have a bountiful feast. The colored children burnt out by the mob will be taken care of at Carmansville.”

Below: Boy with a turkey, circa 1910-1915 (LOC)

Generally speaking, celebrations went forward as they would in subsequent years — the food, the church services, the carousing, the merriment, decades before anybody would think of blowing up gigantic balloons and dragging them down Broadway.

However, one thing had been very different that year. On the evening before Thanksgiving, New Yorkers looked up into sky and witnessed a partial lunar eclipse.

While the event might have filled some with dread, it cast a mysterious pall further south, on the battle field of Lookout Mountain in Chattanooga, Tennessee. It occurred hours after the Confederacy’s defeat by the Union army and helped shield the Southern forces as they slipped away by cover of fog.

Alongside news of New York’s embrace of Thanksgiving, the newspapers that day reported of a victory and a death toll: “General [Joseph] Hooker, in command of General Geary’s division, Twelfth corps, General Osterhau’s divison, Fifteenth corps, and two brigades, carried the north slope of Lookout Mountain, with small loss on our side, and a loss to the enemy of five hundred or six hundred prisoners: killed and wounded not reported.”