One hot summer’s morning, in the neighborhood of Yorkville on the Upper East Side, high school student James Powell was shot and killed by police officer James Gilligan.

Powell either attempted to stab the officer or else the unarmed boy was brutally set upon by a man with violent tendencies. Gilligan, a war veteran, was either defending himself from a troubled delinquent or else he gunned down the teenager with little remorse.

There were few actual witnesses but dozens of bystanders. The incident took place across the street from a high school, and the students, incensed by rumors and the fear of blood running in the streets, began panicking.

The year was 1964.

It’s hard not to read the opening pages to Michael W. Flamm’s gripping In The Heat Of The Summer: The New York Riots of 1964 and the War on Crime (University of Pennsylvania Press) and not see the parallels to modern police brutality cases.  So many different testimonies obscure the truth that it’s hard to know what really did happen in front of 215 East 76th Street that day. (Video footage might not have even cleared it up.)

It’s hard not to read the opening pages to Michael W. Flamm’s gripping In The Heat Of The Summer: The New York Riots of 1964 and the War on Crime (University of Pennsylvania Press) and not see the parallels to modern police brutality cases.  So many different testimonies obscure the truth that it’s hard to know what really did happen in front of 215 East 76th Street that day. (Video footage might not have even cleared it up.)

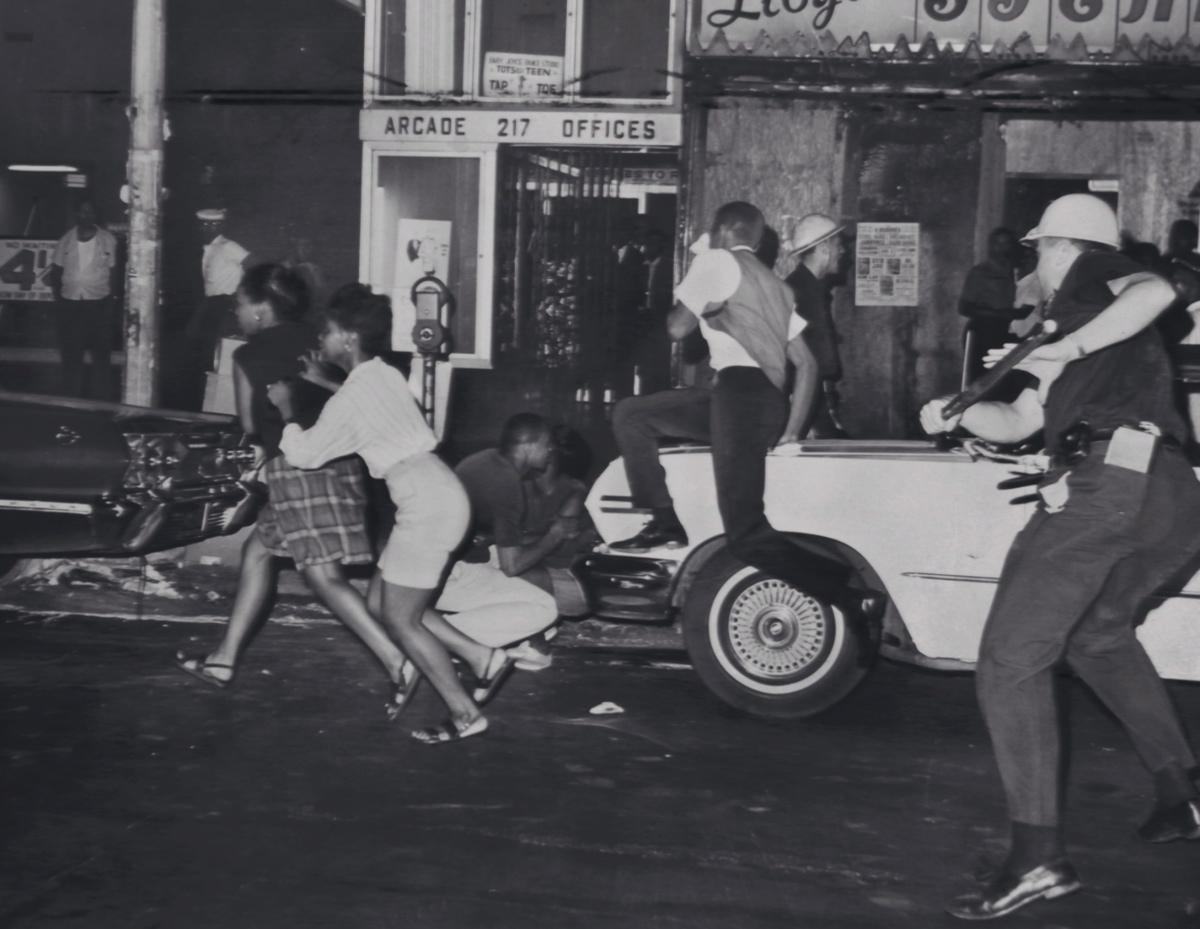

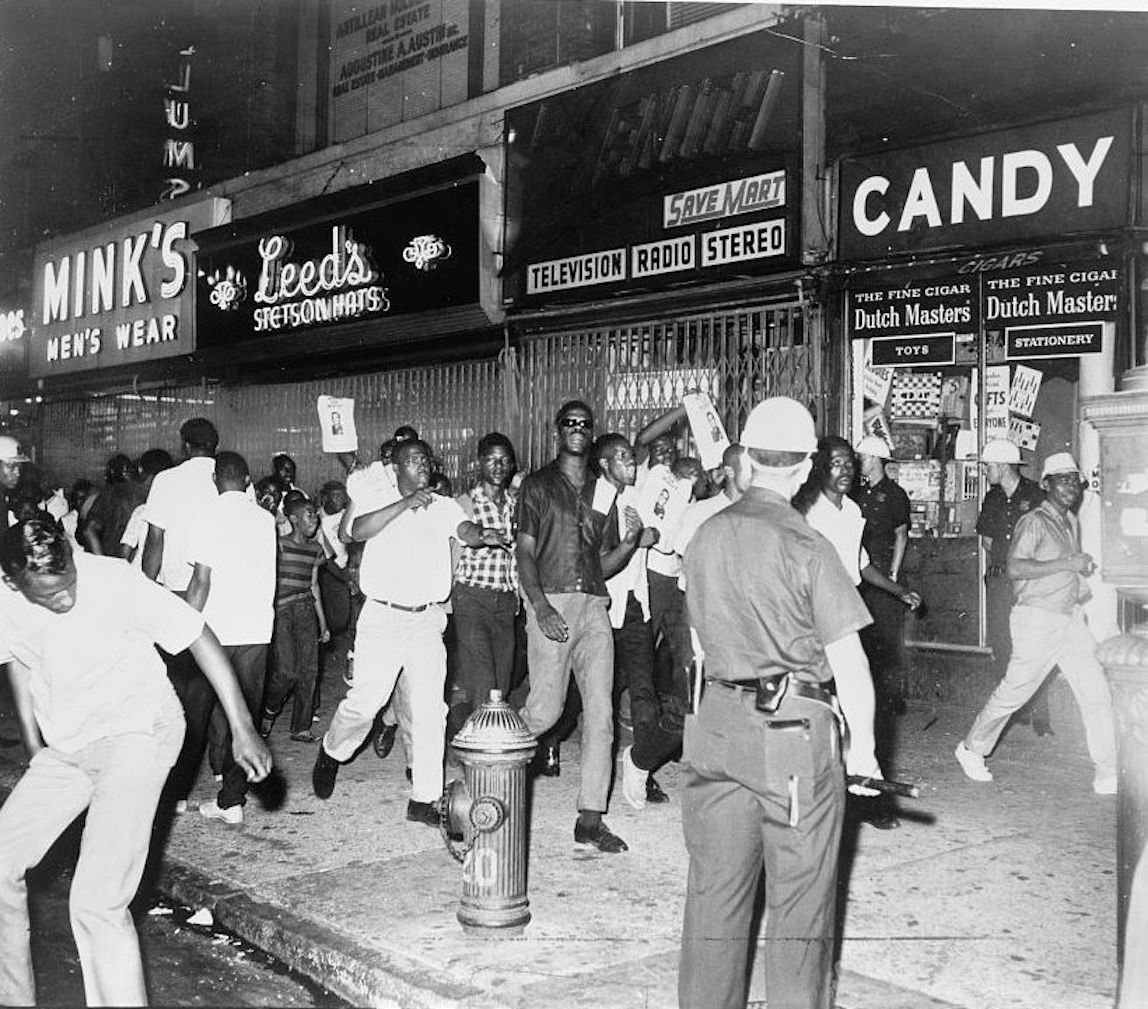

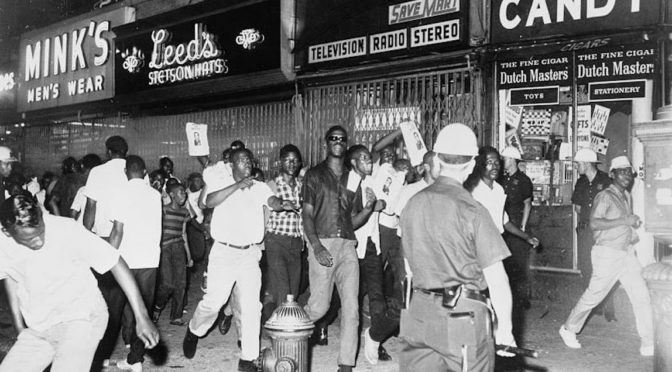

Yet Flamm’s book isn’t specifically about the crime, but the chaos which ensued — the New York Riots of 1964 (with the most violent night often referred to as the Harlem Riot of 1964). For several evenings following the shooting, a host of speculations and false rumors — mixing with grief and despair on a series of hot summer evenings — led to roaming violence and looting in Harlem (with some also reported in the Brooklyn neighborhood of Bedford-Stuyvesant).

The incidents which occurred that summer stem from hostilities which had built up within the black community for decades. A great distrust between the police and African-Americans played a part in the rising crime rate in poor neighborhoods like Harlem in the 1960s.

Fearful residents felt powerless against increasing criminal behavior and drug abuse in their streets but didn’t risk involving law enforcement, who most considered corrupt and racist.

White residents avoided black neighborhoods — and vice versa — due to wildly dramatic reports in the press. Black power movements like the Nation of Islam escalated talk of violence while, in some neighborhoods, white vigilantes stopped and interrogated every black person found in the streets.

Writes Flamm: “New York sounded to the rest of the country like some frontier town helpless before the uncontrollable violence stalking its streets.”

Flamm follows two parallel threads, both coming together in raw, unexpected ways. The first is a terrifying minute-by-minute account of the late-night street riots, the chaotic protests and the rallies organized by those who wished to funnel that rage into a mechanism of change. The second is the reactions of politicians and civil rights leaders to New York’s race and law enforcement problems.

The author’s meticulous research finds microcosms of hate and fear at nearly ever corner — of the kind which will make nobody particularly nostalgic for the period. “Central Harlem seemed like a war zone, with screams from people and cracks from bullets as they ricocheted off brick walls and cement sidewalks.”

At the center of the story is civil rights leader Bayard Rustin (pictured above) and the Congress for Racial Equality (CORE), often caught between keeping and promoting the peace and quelling the concerns of angry residents.

At one point, Rustin was literally disarming people. “The toll might have gone much higher if not for Rustin, who personally disposed of three cases of dynamite — enough to destroy a city block — after two young black men agreed to give it to him instead of using it.”

Few history books I’ve read in the past twelve months have felt as immediate as In the Heat of the Summer, with anecdotes that seem to speak pointedly to the events of today’s headlines.

For example, some police authorities applauded television coverage of the riots. Said one commissioner: “It’s the best answer we have to the cries of police brutality. The camera, after all, cannot distort or lie; the worst that can happen is that the film is edited. But what you see on the home screen is the actual occurrence.”

1 reply on “The New York Riots of 1964: Violent history with a haunting familiarity”

[…] NPR: New York’s ‘Night Of Birmingham Horror’ Sparked A Summer Of Riots (Video) The Bowery Boys – The New York Riots of 1964: Violent history with a haunting familiarity YouTube: Harlem Race Riot 1964 […]