Bayard’s Mount, one of the highest points in Manhattan, has been gone for more than two hundred years. Where other hills and high points have been incorporated into the modern topography New York, this old hill was wiped from the map.

Bayard’s Mount used to sit at around where Mott and Grand Streets meet today, in today’s Little Italy. Indeed, back when nearby SoHo was but a dense thicket of oak and tulip trees, the Mount was the best place to view the waters of Collect Pond, the wild northern orchards, and the flat tidal creeks to the west.

A smaller hilltop, called Mount Pleasant, sat to its east and, with the introduction of Europeans, a farm road (Bowery) ran along it. Sitting atop Bayard’s Mount, a person could wile away the day watching travelers going along the Bowery, to and from the city.

A watercolor by artist Archibald Robertson in 1798, looking south, with Bayard’s Mount/Bunker Hill to the left and Collect Pond dead center.

Some reminiscences refer to Bayard’s Mount and Mount Pleasant as the same hill, and they were close enough they seem to be part of the same ridge.

After the territory went from Dutch to British hands in the mid-17th century, most of this property fell into the hands of Nicholas Bayard, and the “small, cone-shaped mount” took on the name of its landowner, who built his sturdy estate just to its north. Even by the early 18th century, Bayard’s family would still have few neighbors; swampy ground prevented much development west, while property to the east eventually belonged to James DeLancey, the governor of the colony.

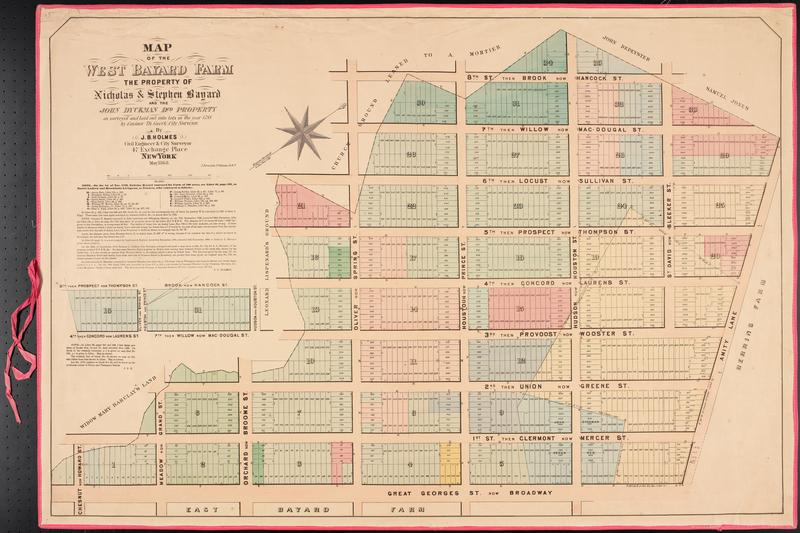

Below: A later 19th century property map highlights the broken western border of Bayard’s farm. The wetlands known as Lispenard’s Meadow prevented the estate from developing further westward.

The mount took on a more serious purpose with the onset of the Revolutionary War. In March of 1776, “One third of the citizens were ordered out to erect new works; they began a fort upon Mr. Bayard’s Mount near the Bowery.” [source]

This fortification, built in anticipation of a messy battle with the British, was named after a critical battle the year previous at Bunker Hill in Boston; soon, the hill itself took on the name, and in most histories after 1776, this place at today’s Mott and Grand Streets is officially known as Bunker Hill. Notably stationed here at Bunker Hill was Nathan Hale.

There would be no significant altercations here between British troops and the Continental Army. No, in fact, the bloodshed would wait until after the war, when the hilltop would be known as a fashionable place to host your duel.

For instance, in 1787, a disagreement between two French men ended in a duel here and the death of one of them, a “Monsieur Chevalier de Longchamps” who was apparently no stranger to offense and violent response.

Below: From Montressor’s map of Manhattan, 1755, you can see Bayard’s property and both hills — Bayard’s Mount and Mount Pleasant, the elongated hill. The Bowery runs along the bottom right hand of the illustration, with Collect Pond in the bottom left corner. You can also see the grid plan of Bayard’s farm (which was ultimately adapted for the modern street plan of SoHo).

In July 1788, to celebrate the federal ratification of the Constitution, a procession marched through the city and ended its revelry at Bayard’s Mount/Bunker Hill, where “ten enormous tables laden with provisions” and hundreds of pounds of roasted ox were served to hungry patriots. Several years later, in 1795, a different gathering, angered by their governor John Jay over his (perceived) treasonous treaty with the British, burned his portrait in a bonfire here.

Another curious pastime at the hilltop was the British sport of ‘bull baiting’, where a bull would be tied to a stake and slowly tortured by angry dogs. Why this is of any visible amusement is beyond me, although its cousin ‘bear baiting’ is still sometimes practiced in Pakistan.

Below: A bit of this nasty little pastime out in Long Island as it was advertised in 1774

New York was outgrowing the southern point of Manhattan, and former deterrents for expansion — the marshes of Lispinard’s Meadow, polluted Collect Pond, and of course, Bayard’s Mount — were slated for elimination. The ponds and marshes would soon be drained, creating Canal Street, and Broadway expanded further north. (Listen to our podcast on Collect Pond and Canal Street for more information.) By then, Bayard’s was but a memory.

Beginning in 1802, workmen began levelling Bayard’s Mount and Mount Pleasant which also included moving the old Bayard family crypt which had its entrance at the bottom of the hill. Unfortunately, it was discovered that a “hermit or ragman” had moved into the vault and turned it into his very own macabre home. Remarkably, the man was allowed to live there — “he was somewhat feared and not much troubled by visitors” — until he was found one day dead in the vault.

By the time Collect Pond was completely drained (around 1811), the hills to its north had gone, replaced with land lots and the first hints of townhouses and new businesses.

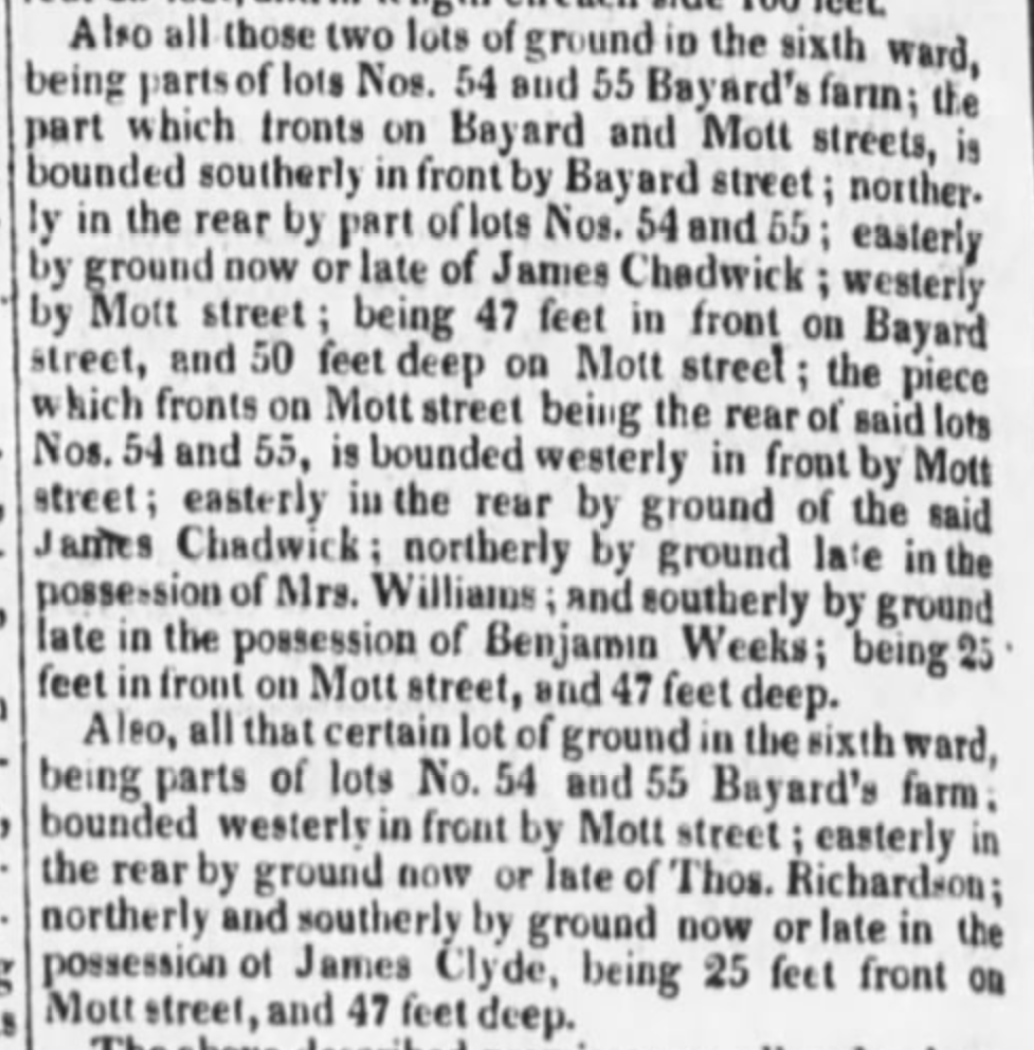

Below: From an 1821 New York Evening Post, an advertisement for plots on the old Bayard farm — at Bayard Street and Mott Street, just a couple blocks south of the location of the Mount

Another clipping from an 1888 New York Evening World, recalling the landscape here:

Below: The approximate position of where Bayard’s Mount would have been:

A version of this article originally ran in October 2010

5 replies on “The Story of Bayard’s Mount, Lower Manhattan’s Missing Mountain”

Very interesting! I’m often in the neighborhood, and it’s fascinating to know that it was once such a bucolic and wild place.

This makes me think of the neighborhood in Paris known as “Le Marais,” which means “The Marsh” and was literally just that.

The timing makes me wonder if the earth taken from leveling the hills was used to fill in Collect Pond.

Yes, acc. to the entry in wikipedia for Collect Pond, the earth from the hills was use to fill in Collect Pond. A story in itself.

thanks for sharing

Looking at Montresor’s map (and another presented to the American Philosophical Society in 1833 but drawn earlier: http://www.historicmapworks.com/Map/US/1608995/New+York+City+1830c+++APSdigobj3528/New+York+City+1830c/New+York/), the ridge begins around Elizabeth St, but the peak of Bayard’s Mount/Mount Pleasant/Bunker Hill is WNW of Mulberry St, a little more than a block away from Winne/Motte St.