There is no place in New York City quite like the converted factory building at 538 Johnson Avenue in Bushwick*, Brooklyn.

At the same time, it evokes in mysterious ways a compelling truth about this city — that every building has a story, if only it had a storyteller to share it.

For 538 Johnson, that storyteller is Bryan Sears, an artist who has lived in a loft here since 2007. He has transformed one floor of this space into a unique museum to its own history, employing a unique printing technique to adhere historical photographs and records along winding hallways.

Along the way, he and his collaborators (Karen and Brian Marx Gibson) have created something almost unprecedented — a museum to the industrial past, with a personal, handcrafted touch that feels appropriate for a building that has done nothing but create.

“I was excited by all the factory architecture and wondered what these buildings were made for,” said Sears, “and it’s sad that the past of the structures is forgotten. I think buildings are like ships; they have characters and “souls” which should be honored.“

Sears is more than a self-styled museum caretaker. His work has prepared the structure for the next phase of its life — as a legal residence.

Current businesses occupy two floors of 538 Johnson, while the other two floors have housed residents — illegally — since the 1990s.

In July, a newly signed Loft Law bill will allow residents like Sears to stay in the building, but a change in status may open the un-landmarked building to radical renovations.

Sears’ exhibit at 538 Johnson is offering a kind of protection for the building.

“The legends of the doll factory and the artifacts collected by the tenants were hints of the past,” said Sears, “and I just found it irresistible and so satisfying to come up with the answers.”

A few weeks ago, Sears (along with photographer Alexander Rea) took me on an extensive tour of this private exhibition, then we wandered around a seemingly endless maze of corridors — through spray-painted stairwells and rooftops — inspecting the building’s many architectural mysteries.

Bushwick Industrial

Bushwick, tracing back to one of the earliest European settlements on Long Island, has never been the prettiest area of modern Brooklyn.

It does have some lovely architecture — especially around old Brewers Row — but its proximity to a polluted water way and a series of cemeteries has always kept this underappreciated neighborhood below the radar — historically speaking.

Bushwick was actually one of the first European settlements in Long Island, originally named Boswijck by the Dutch. By 1854, the Town of Bushwick, independent for almost two hundred years, officially became a part of the growing City of Brooklyn.

Like Williamsburg and Greenpoint — the other two neighborhoods of the old Eastern District — Bushwick has always been defined by production — from farms, then from factories. For instance Peter Cooper built his considerable fortune from a massive glue manufacturing plant located just a few blocks from the location where 538 Johnson would be built.

By the late 19th century, decades of industrial use had transformed the banks of nearby Newtown Creek into a pungent mess, its waters blotted with pollution from local refineries and dumps.

Imagine an aroma of intense, unregulated chemicals, smoke, manure and even animal corpses. (After all, animal hooves were vital in the production of glue.)

A wide variety of manufacturers spread out to be closer to the creek and to the Long Island Railroad, which opened a freight railroad branch through Bushwick in 1868, speeding products and supplies in and out of this section of Brooklyn.

Making the Beds

538 Johnson Avenue (at Stewart Avenue) was constructed in 1916 as a simple two-story warehouse owned by the Pashelsky Brothers, a building supplies concern, who specifically situated their operation next to the railroad tracks. They soon outgrew their home and sold it to a surprising new tenant — a mattress factory.

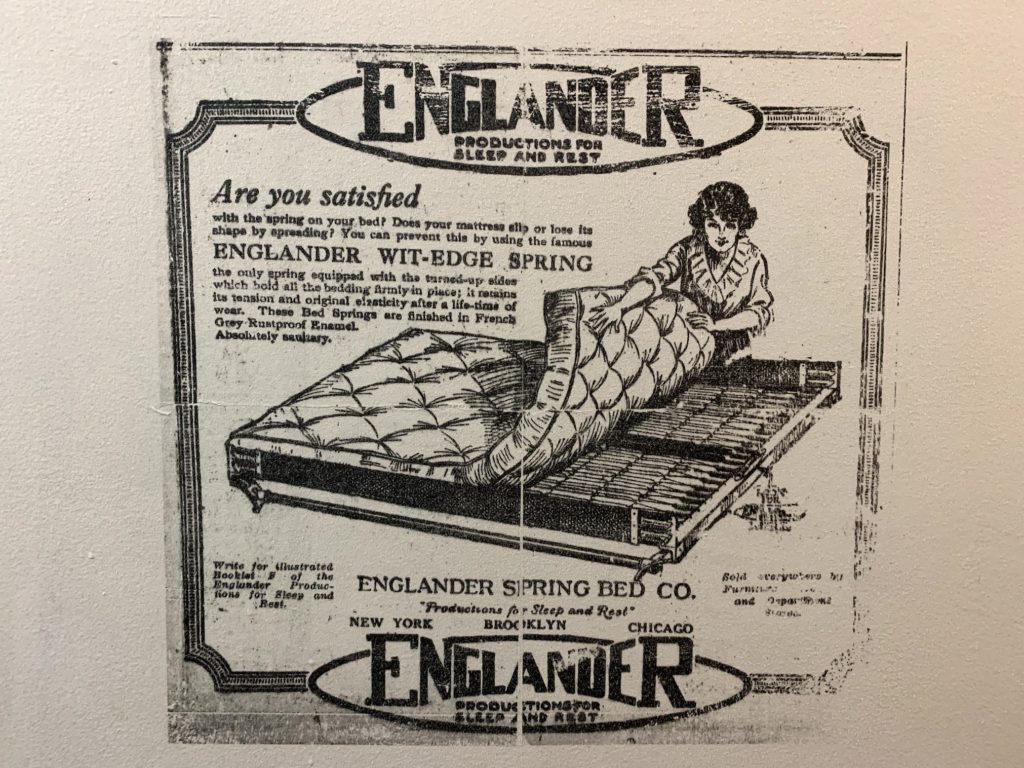

In 1894 Englander Spring Bed Company began its long career of making mattresses and box springs at Bush Terminal near the neighborhood of Sunset Park. They’re actually still around today and, for a time, their home was here at 538 Johnson. (The U.S. government kicked Englander out of Bush Terminal when they took it over during World War I.)

In Bushwick, Englander expanded 538 Johnson into four-story structure with a large loading dock, hoisting newly made mattresses and bed accoutrement into train cars for bedrooms nationwide.

During the 1930s and 40s, Englander employees could even enjoy watching a baseball game at the nearly Arctic Oval field, a welcome escape from Bushwick’s drear industrial uniformity.

By the following decade, Englander had moved on and 538 Johnson found a new tenant — dolls.

Enter the Dollhouse

Many of you over a certain age probably owned a doll manufactured at 538 Johnson.

Eugene Goldberger was a Hungarian immigrant who began making dolls in the area of today’s SoHo district in 1916. While Goldberger maintained showrooms in lower Manhattan for many decades, he moved his doll manufacturing to Bushwick in 1954.

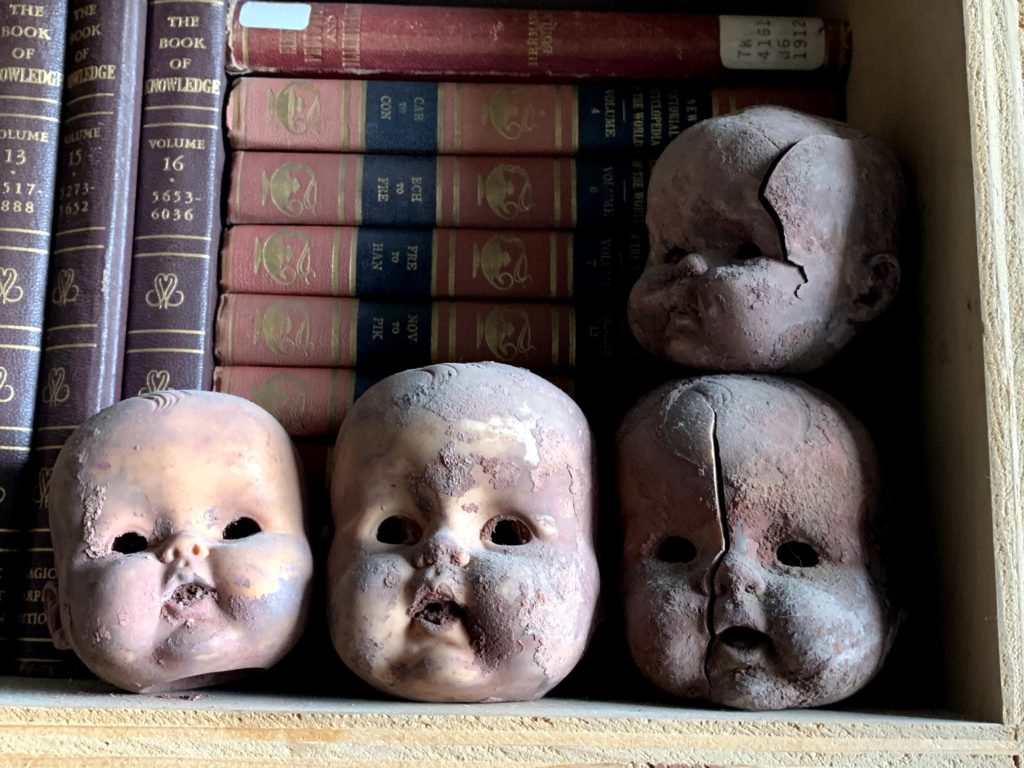

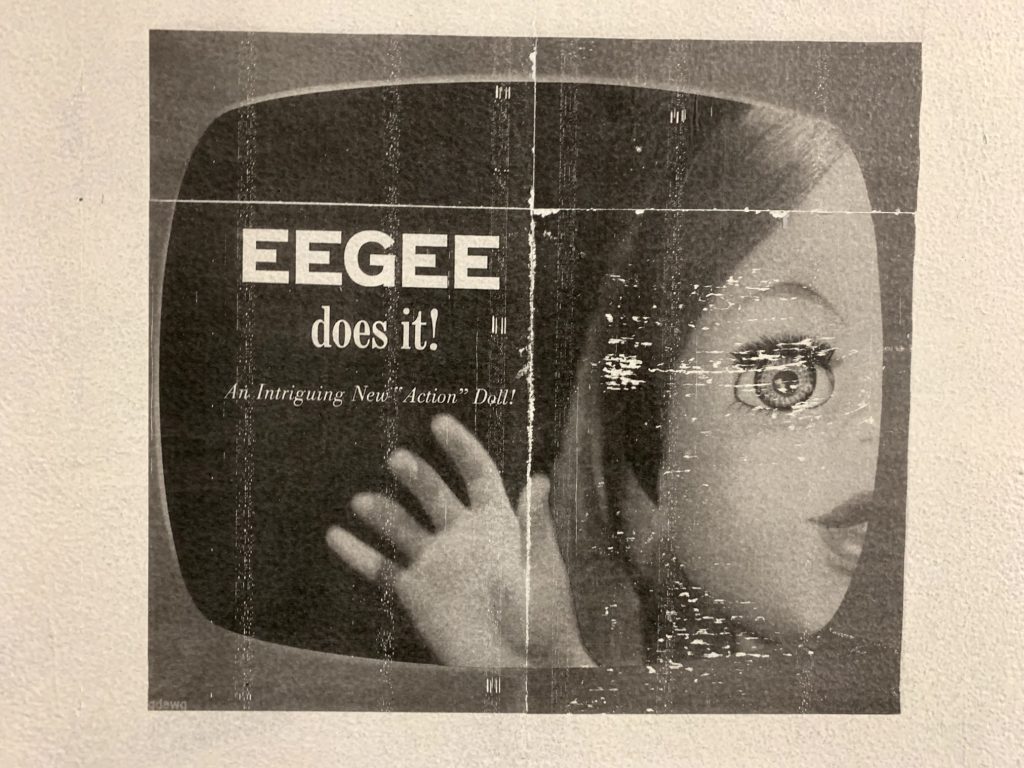

Today Goldberger dolls are the staple of flea markets and vintage stores across the country. Also called Eegee dolls, these toys are traditionally known for their delicately painted features and round chubby faces.

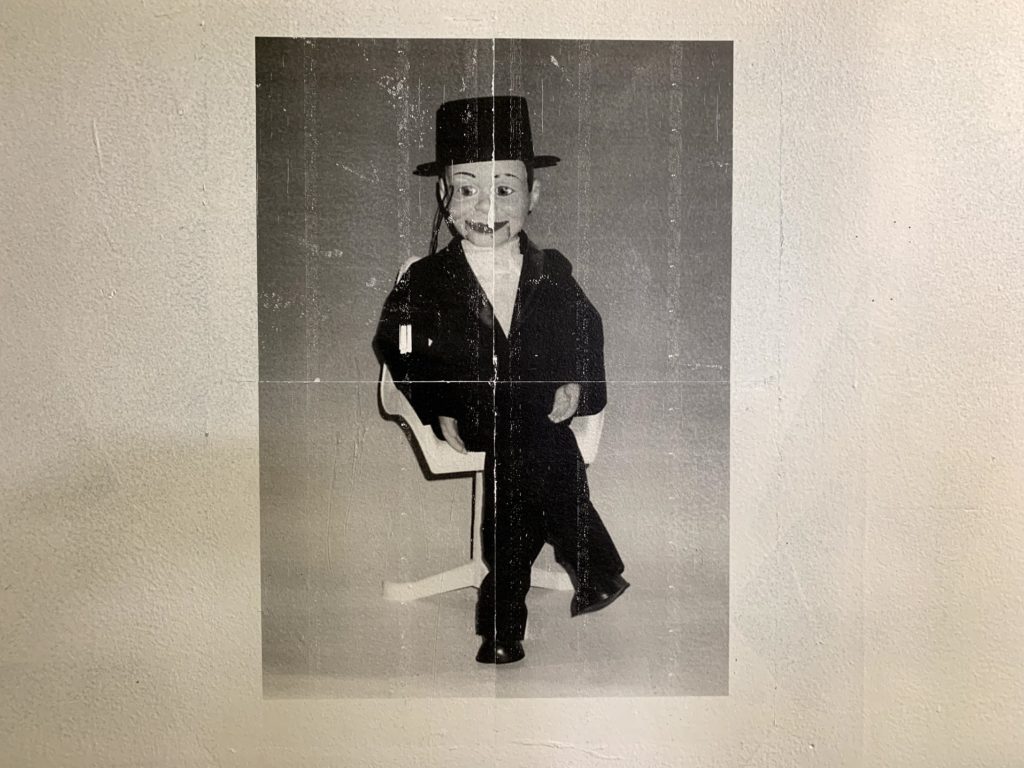

By the 1950s, the company had also branched into dolls with more adult features and even dabbled into some Barbie-inspired realness. And Goldberger also got in to the licensed doll game, manufacturing many replications of famous ventriloquist superstars like Charlie McCarthy, Howdy Doody and Lester.

Sears had a catalog listing of dolls that were manufactured here that he allowed me to thumb through:

In the 1970s Goldberger even installed an impressive series of conveyor belts within the factory, delivering a stream of newly crafted dolls to waiting cargo trucks.

Like Englander, the Goldberger Doll Company is still manufacturing toys today — as Baby’s First Doll. But they moved out of 538 Johnson in 1984.

Crisis Times

By this time, the fortunes of Bushwick’s once-great industrial might had drastically deteriorated. Manufacturing had fled, leaving a landscape of empty factories, and the neighborhood generally became known as an “epicenter for the illegal drug trade,” its poor residents suffering high crime rates and a lack of genuine city infrastructure and support during the 1970s and 80s.

It was around the late 1980s that Manhattan artists, pushed out of now-pricey neighborhoods like SoHo and Tribeca, began gentrifying the Brooklyn neighborhoods of Williamsburg and Greenpoint — both experiencing similar downturns in manufacturing.

A few adventurous souls, looking for loft space in less obvious zones, began looking at Bushwick’s many half-empty buildings in the 1990s. It’s at this point that 538 Johnson, with only a couple floors engaged with actual manufacturing, saw its first residents.

And it was then that the most surprising addition to the story of 538 Johnson arrived — the punks.

“Here It Goes Again”**

Since the early 2000s, a portion of the building has become a mecca for punk music and hardcore lovers everywhere. While the venue is separate from the residences and remaining manufacturing concerns, you can’t escape the graffiti, turning the building into a successor of the dearly departed Five Pointz.

This 2014 performance by Dawn of Humans should certainly give you a sense of the place:

Wandering its pockmarked halls, its well-worn wooden floors, you get the sense of the great ironic versatility of New York City — where churches become nightclubs and botanic gardens become great metropolitan hubs.

And doll factories become punk palaces.

If you’re interested in exploring this one-of-a-kind exhibition, you can arrange for a private tour by emailing Sears at 100years@538johnson.com.

And visit his site about the 538 Johnson here.

On a personal note: I was deeply impressed by how much Bryan and his collaboraters have researched the history of this building in efforts to save it and celebrate it. In every place I’ve ever lived in New York, I have always imagined doing this type of thing — to find those who have walked before you. Well Bryan did it. This is one Bushwick trend I would happily love to see imitated in unexpected spaces across the city.

*Some may prefer calling this area East Willamsburg instead of Bushwick.

**For a time, Andy Ross, guitarist for the band OK GO, managed his record label Serious Business Records from 538 Johnson Avenue.

2 replies on “The Bushwick Doll Factory: A tour of 538 Johnson, where Brooklyn’s industrial past and punk music collide”

Is this tour of 538 Johnson Avenue still being offered?

I remember in the early 60s, an uncle of mine who worked there, gave me a Thumbelina doll for Christmas. You could wind it up and she played music and moved around like a real baby. Never forgot that beautiful, chubby cheeked baby doll.