New York City has a new mayor — Eric Adams! So we think it is time that you Know Your Mayors, becoming familiar with other men who’ve held the job, from the ultra-powerful to the political puppets, the most effective to the most useless leaders in New York City history.

This longtime feature of this website is being rebooted with new articles and newly researched and refreshed earlier entries in this series. Check back every other week for a new installment. Read past articles here.

Mayor Walter Bowne

1829-1832 (four one-year terms)

Walter Bowne, mayor of New York City from 1829 to 1832, was born in Flushing in 1770, many years before the region would erupt into a revolutionary war.

But his story really begins well over a century before. Walter would not have been mayor if not for the distinguished reputation of his family name.

A Flushing Revolution

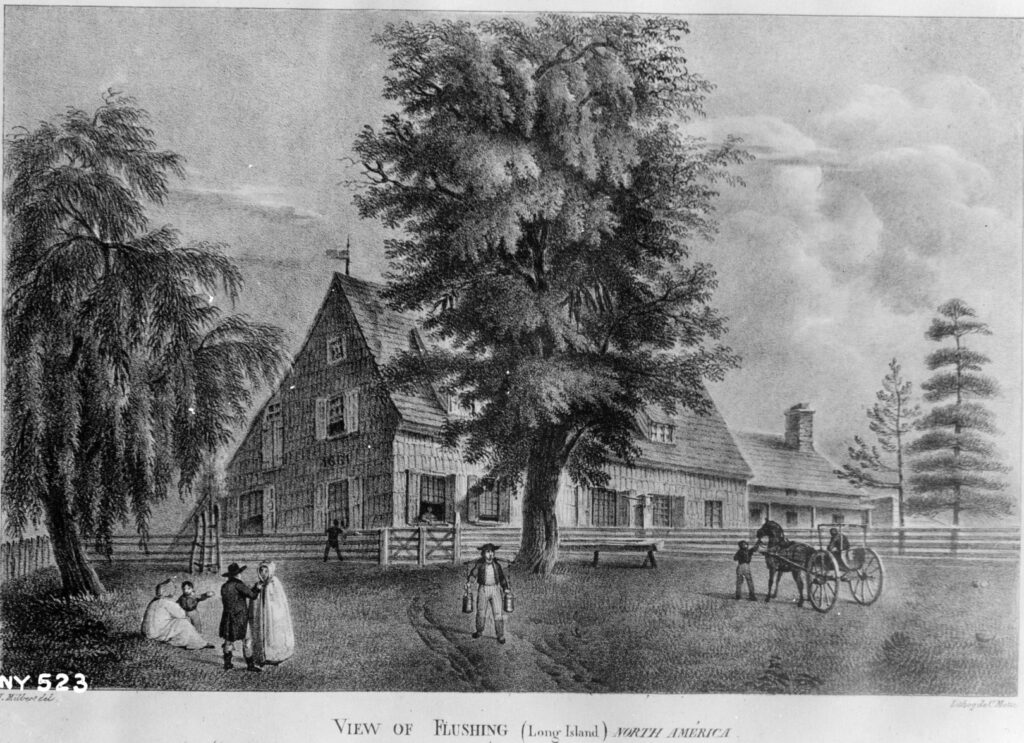

The Bowne family first settled in Flushing (then Vlissingen or Vlishing), Long Island in the 1660s when the region was a part of the Dutch empire, an outpost of New Netherland.

Yet Thomas Bowne, his son John Bowne and their clan were English, and this area of Long Island had been long settled by Quakers.

The Bownes were entering into a religious powder keg. Already by 1657, director-general Peter Stuyvesant considered the religious enclave “a threat to the peace and stability of the colony and probably out of their minds as well,” writes Russell Shorto in The Island At the Center of the World.

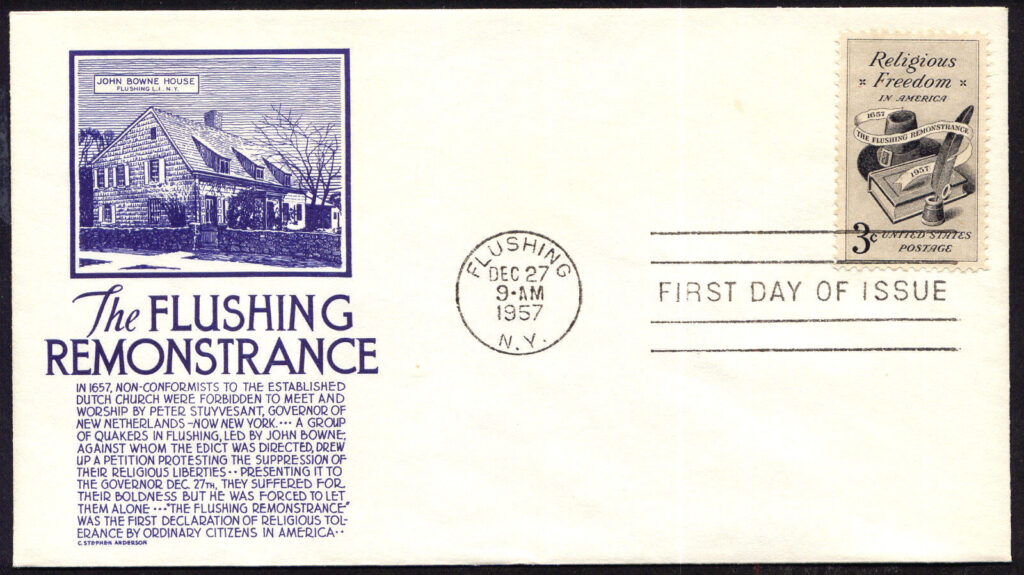

The Long Island Quakers responded with an extraordinary document that year called the Flushing Remonstrance, asserting their freedom to worship under Dutch standards of tolerance and “the law of love, peace and liberty.” This only infuriated Stuyvesant further.

By 1662 the home of John Bowne had become a central meeting place for the area’s Quaker population. Stuyvesant had him arrested and deported to Amsterdam — despite the fact that he was English and Holland was not his country of origin.

However Bowne successfully petitioned the Dutch West India Company and in the end, by 1664, he was allowed to return to Long Island.

Stuyvesant, meanwhile, was severely reprimanded and ordered to be more tolerant. (Fortunately for Peter, the English took New Amsterdam that very year so he didn’t have to officially tolerate anybody anymore.)

The Kings of Queens

The Bownes would become this region’s [i.e the region that would become Queens] most prosperous and politically important families. John Bowne’s home, built in 1661, still stands, one of New York’s oldest and most valuable historic places, a genuine treasure of preservation.

Thanks to John’s battle for religious freedom, the family name would also become a standard bearer for liberty in the years leading up to the American Revolution. Although applying that reputation more broadly is trickier. (For instance John Bowne “owned at least two slaves and an indentured servant.“)

Later descendants would become known as early American abolitionists including Robert Bowne, a contemporary of Alexander Hamilton and John Jay, who helped to form the Manumission Society of New York and later the African Free School.

But Robert would be better known for a publishing firm he established in 1775 — the financial printing house Bowne & Co, today New York’s oldest operating business under the same name.

All of this is to say — when Walter Bowne was appointed by the Common Council in 1839 to be the mayor of New York City, he brought with him the burden of high expectations.

Walter’s Rocky Start

Walter Bowne was of the genteel class which participated in politics during this period. He had also at one time been the Grand Sachem of Tammany Hall, the rising Democratic machine. So when he was first appointed mayor, serving in the year 1829, he was very much considered a machine politician.

But he was almost a one-and-done mayor. Tammany had narrowly lost the majority of Council members in 1829, placing a second year for Tammany’s leader as mayor in doubt. (Mayors were appointed for one-year terms at this time.)

But then Bowne made a controversial power move. According to Gustavus Myers’s A History of Tammany Hall:

“[In December 1829] Fourteen Aldermen and Assistants were opposed to Bowne and thirteen favored him. There was but one expedient calculated to re-elect him, and to this Tammany Hall resorted.

Bowne, as presiding officer of the Council, held that the Constitution permitted him to vote for the office of Mayor. “I will persist in this opinion even though the board decide against me,” he said.

To prevent a vote being taken, seven of Bowne’s opponents withdrew on December 28, 1829. They went back on January 6, 1830, when Tammany managed to re-elect Bowne by one vote. How this vote was obtained is a mystery.“

Bribery was almost certainly involved in this sudden reversal of Bowne’s fortune.

An investigating committee into the events of January 6 was formed to inquire about this mystery, but as the committee was comprised of those who favored Bowne, no proof was ever discovered of such bribery.

Water and Docks

Bowne’s priorities were pure infrastructure. New York was in the middle of a water crisis with the growing city requiring more supply than its current local wells, cisterns and fresh water ponds could provide.

“We have the opinion of two prominent Civil Engineers that the Byram, Rye and Wompia Ponds will afford such supply,” the mayor declared, then casually mentioning the “Bronx, Saw Mill and Croton rivers” as other options.

But New York was waylaid by funding such a water project at this time, and Bowne was unable to get anything of immediate significance done by the time he left office in early 1833.

Two years later the Great Fire of 1835 underscored the urgency of an improved water system. The Croton Aqueduct system, bringing New York much needed water, finally opened in 1842.

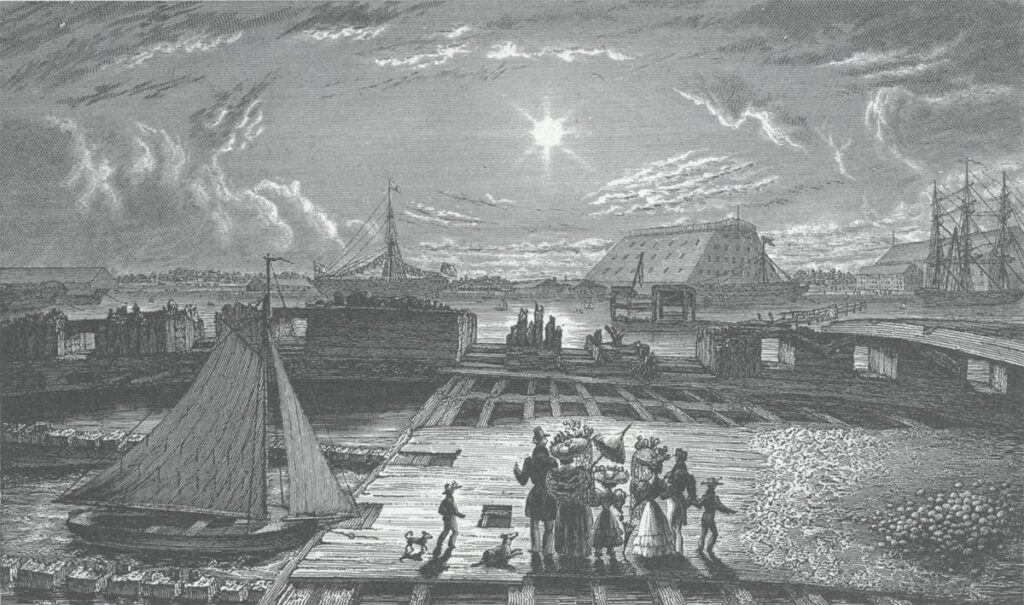

New York’s other great priority was the Erie Canal which had opened in 1825.

Bowne was driven to action by the revered Henry Rutgers who died in Bowne’s first year in office. Rutgers had written to Bowne “expressing great anxiety lest our harbor, which has scarcely an equal in the world should be injured” by the continued building of wooden and dirt piers — ill-equipped to handle the growing international trade.

Under Bowne, work began on constructing an overall improvement of the waterfront for industrial use, with sturdier piers of stone and new warehouses.

This foresight would eventually benefit to growing steamship trade and another transportation revolution arriving soon — industrial railroad freight.

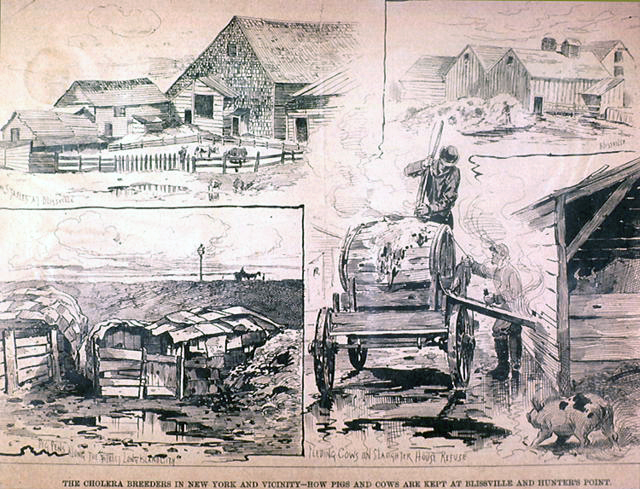

Cholera Crisis

The ill-preparedness of New York for the full implications of trade were in full effect in 1832, when a major cholera epidemic came to the city.

The state of New York already had a quarantine hospital in Staten Island in place for arriving ships coming through the Narrows. But this did not prevent the disease from coming into the city from other directions.

According to Bowne House historian David Silvernail, “the [cholera] outbreak started in surrounding areas and to prevent it from reaching the city, Walter decided to enact a quarantine for all ships and carriages attempting to enter the city. This included all of the products and people on board.”

Bowne’s quarantine required that all ships keep at least 300 yards from the city’s ports. And carriages arriving from the north were stopped 1.5 miles from the city limits.

Under Bowne the city also engaged in a vigorous clean-up of its streets (although as Bowne House historian Silvernail reveals, the efforts were inadequate):

“Bowne’s well-meaning attempts to prevent a cholera outbreak failed, and hundreds of New Yorkers died of the disease,” according to NYC Parks. “It was not until 1883 that the German physician Robert Koch discovered that cholera spreads through contaminated water or food.”

A Lasting Landmark

Bowne left office in early January 1833 and, among other things, became the president of 7th Ward Bank of New York City. At times he also retired to his summer home in Flushing, the location of which is today’s Bowne Park. Bowne died in 1846.

New York enjoys many locations associated with the Bowne family. On top of Bowne Park and the Bowne House — both perfect places to visit this fall — Bowne & Co. Stationers provides a glimpse into America’s printing legacy in a rustic shop at the South Street Seaport.

1 reply on “Mayor Walter Bowne and his very exceptional family story”

Very curious. My name is Walter Bowne. Tracing some family history. My grandfather and father were from Camden, NJ. Love reading the history. No one knows how to pronounce name. Down with Bowne? lol.