New York City has a new mayor — Eric Adams! So we think it is time that you Know Your Mayors, becoming familiar with other men who’ve held the job, from the ultra-powerful to the political puppets, the most effective to the most useless leaders in New York City history.

This longtime feature of this website is being rebooted with new articles and newly researched and refreshed earlier entries in this series. Check back every other week for a new installment. Read past articles here.

Mayor Aaron Clark

1837-1839 (two one-year terms)

Aaron Clark has many claims to fame in New York City history, none of them really things that recommend him as a defining leader of our city. His most defining characteristic was that he was often very lucky.

Clark is the first mayor ever elected representing the anti-Democrat, anti-Andrew Jackson Whig Party — a political party abolished less than 20 years after Clark’s victory.

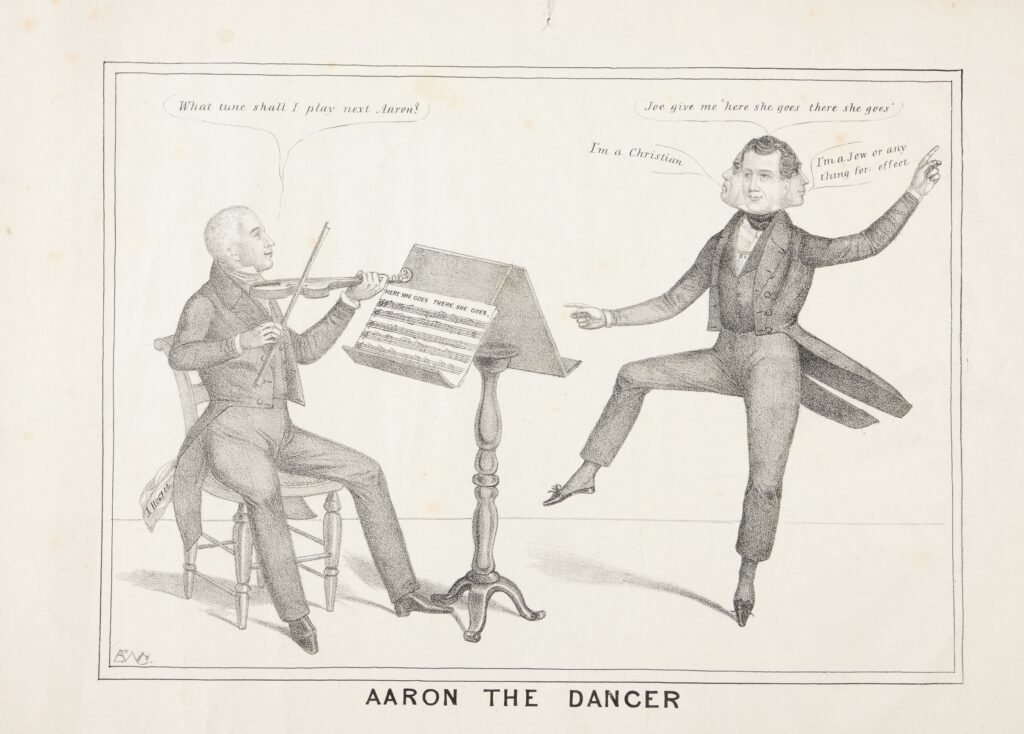

He was known as the ‘Dancing Mayor’, which was not an accomplishment but a mockery.

He called himself the New York’s most prestigious lottery operator, which he considered an accomplishment but was perceived by some as a disqualification.

And finally he was elected amidst one of the worst financial crises in its history– the Panic of 1837.

Previously on ‘Know Your Mayors’

Clark, perhaps more honorably, was also the second man to ever be popularly elected as mayor of New York, i.e. chosen directly by the people of the city.

Previously, the position was selected by the Common Council (city council), district representatives who often chose men beholden to their whims.

When the state finally changed mayoral selection to one of popular election in 1834, the result caused violence at the polls and mass pandemonium. (See the last installment.) Cornelius Lawrence would come out ahead for three consecutive one-year terms.

Lawrence had been a candidate of Democratic machine Tammany Hall — with their influence, who else would be the first mayor? — but Democrats were facing strong opposition from an ascendent Whig party.

The Whigs and the Locos

In fact, the Whig candidate in 1834, Gulian Verplanck, very nearly won; the animosity between the Democrats and Whigs was so contentious that right before the election, Tammany thugs stormed their opponents headquarters, destroyed everything inside and even killed a man.

During Lawrence’s tenure, the Whigs remained strong as the Democrats got weaker.

In a situation which certainly has some reflection in current national events, Tammany was split between conservative and liberal factions (an ‘Equal Rights’ faction, as they called themselves).

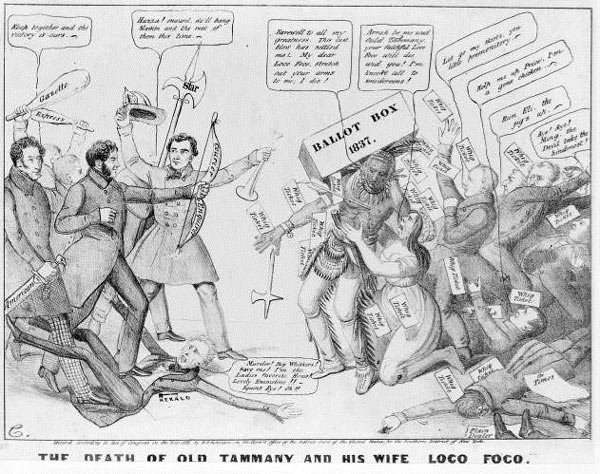

During a Tammany meeting in 1835, the Equal Righters stormed a Tammany committee meeting loaded with conservative members and threw them out.

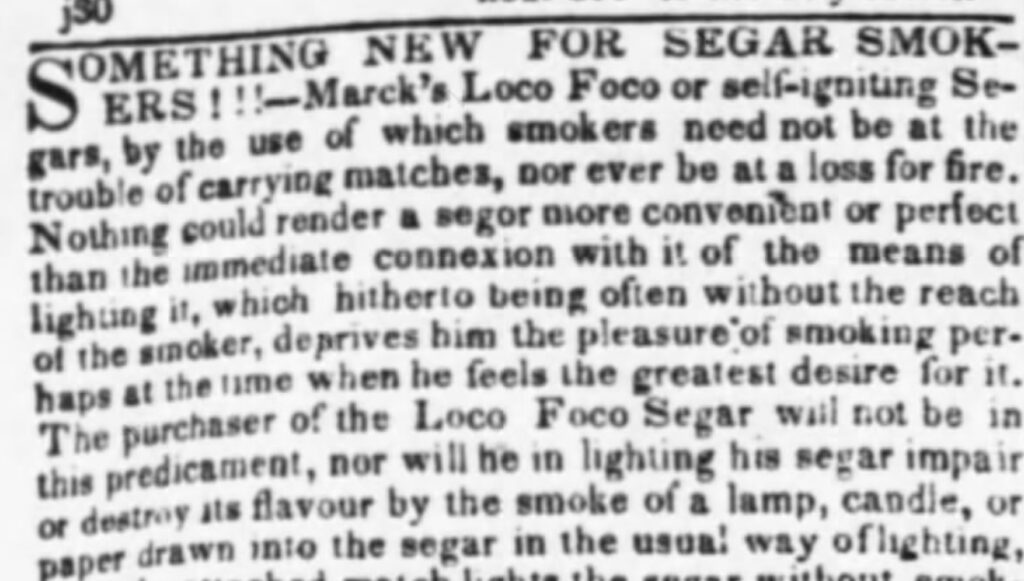

When the lights were turned out on the party-crashers, they lit Spanish matches or ‘loco-focos‘ and continued. The opposition, which would eventually run the conservatives right out of the party, would forever be known as the Locofocos. (For more on their particular beliefs, read here.)

How Luck Elected A Whig Mayor

So what does this have to do with Whig man Aaron Clark? At another period in history, Mr. Clark might never have gotten to experience life in City Hall.

But the dissention within the Democrats opened the door for the fleeting Whig party to reign briefly in New York. With that sort of luck, it’s no surprise to learn that Clark’s primary occupation up to then was as operator of a lottery business.

Privately-run lotteries were, believe it or not, quite common in early American history.

King’s College (today’s Columbia University) was founded with a lottery pool. A young P.T. Barnum operated one up in the 1820s. Benjamin Franklin and George Washington both held fund-raising lotteries in their day.

Even Alexander Hamilton opined that “everybody … will be willing to hazard a trifling sum for the chance of considerable gain.”

By the mid 19th century, private lotteries would be associated with more disreputable elements and would be abolished at the end of the century. Clark was thus a successful operator of an industry in the 1830s that would soon be looked upon as scandalous and unseemly.

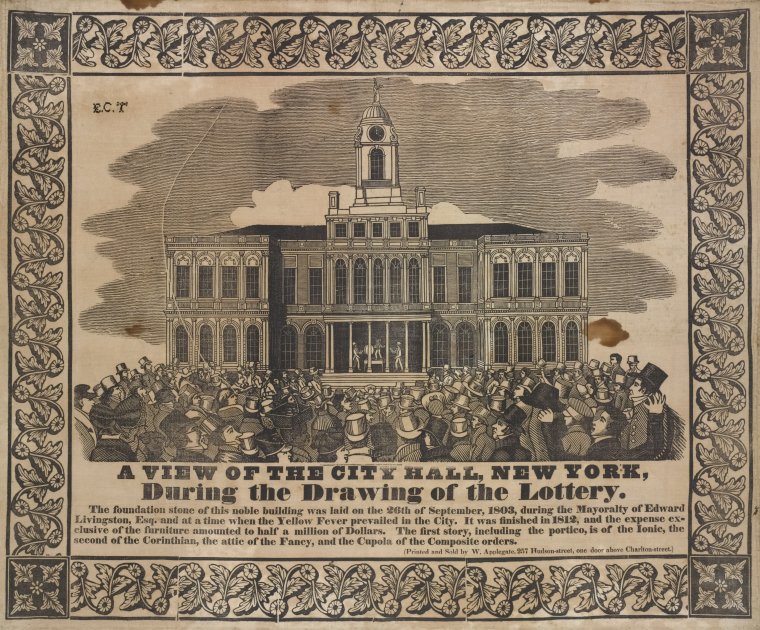

However, in 1837, it was a highly regulated but legal trade. In Charles Haynes Haswell’s classic Reminiscenses of New York by an Octagenarian, Mr. Haswell writes:

“As lotteries, under certain regulations as to the drawings, which were had upon the esplanade in front of the City Hall, in the presence of an alderman, were authorized by law, there were many offices in the city, notably one at the southwest corner of Broadway and Park Place* kept by Aaron Clark, a much reputed citizen.”

*The Woolworth Building now stands on the spot where Clark’s business once stood.

“He was a great lottery seller and made a fortune of it,” says one source. A recollection from an 1890s New York Times article shortlists Clark as one of the “best known rich men” at the time.

Huzza for Clark, Fortune’s Favorite!

Clark was born in 1787 in Massachusetts, a veteran of the War of 1812, and spent his early years as a clerk of Albany state assembly.

He moved to New York to pursue banking and eventually fell into his lottery endeavors, becoming wealthy and, by extension, highly suitable for early 19th century public office. Clark was soon elected to an alderman’s seat, typically a neat launching pad into the mayor’s chair.

The Whigs announced him as their candidate in 1837 against the intensely split Democrats. Conservative Tammany ran John Jordan Morgan, while the Loco-Focos put up the interestingly named Moses Jacques, considered “the patriarchal leader of the Loco-Focos.”

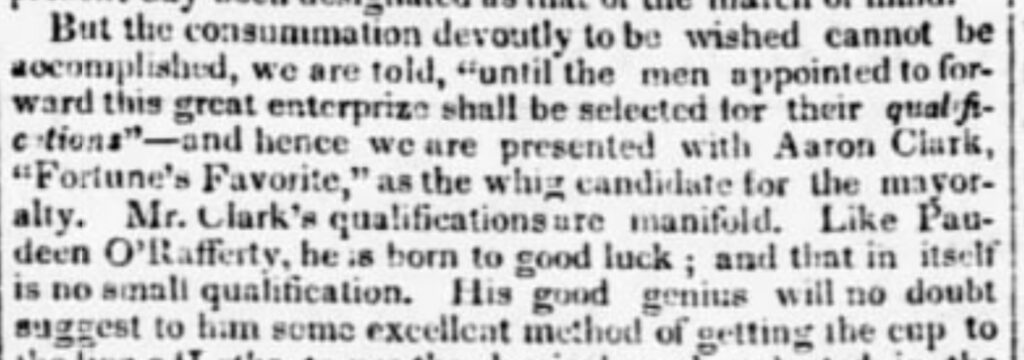

Clark’s opponents certainly tried to use his occupation against him. Wrote William Leggett : “If we elect Aaron Clark for Mayor who knows but he may get up some ‘splendid scheme’ and insure ‘a grand prize’ to everyman who assisted in making him manager of the municipal lottery. Huzza for Clark, Fortune’s Favorite!”

However Morgan and Jacques cleaved the opposition in two, and for the first time in New York history, on April 11, 1837, a Whig became mayor.

He then would be re-elected in 1838 when Tammany’s conservatives threw their support to him out of spite towards their liberal LocoFoco brethren. (There was apparently a shocking amount of fraud going about that year, which also helped matters.)

Fortune’s Favorite?

Clark was certainly the wrong mayor for the moment. He was an ardent Native American, meaning he generally despised the boatloads of Irish emptying into New York slums, driving “the native workmen to exile,” he said in a meeting to the Common Council.

His campaign was openly hostile to ‘clannish’, ‘untrustworthy’ Irishmen, and his tenure as mayor only stirred up xenophobic sentiments. He advocated for keeping new immigrants on ships, directing them away from city and charging them ‘commutation fees’ of $10.

Clark aimed his racial paranoia at the lower classes at large, fearing that the charity organizations already in place were turning the city “into a rendez-voux of beggars, paupers, vagrants and mischievous persons,” according to the book Gotham.

One general benefit of this alarming hysteria was an improvement to the system of nightwatchmen and security patrols throughout the city, a “military arm” to assuage rioting and general chaos. Clark was no light-weight; he would frequently lead these local militias through the city himself, breaking up rabble-rousing groups.

The Unfortunate Fop

Most unfortunately, however, Clark’s charms were limited. His attempts to woo over New York’s elite in a series of parties at his home on Broadway and Leonard Street fell flat.

This type of social governance was a winning recipe for mayors like the honorable Philip Hone. As mentioned in a prior installment of this column, Hone’s parlor “hosted a nightly gallery of political and foreign dignitaries mixing it up with New York’s social strata.”

Clark, however, was roundly ridiculed for attempting such grand ‘entertainments’. In fact, in an early form of political snark, Clark was ironically called ‘the Dancing Mayor’, not for his graces assumably or even the class of his “splendid patent leather pumps” but for his pretensions of trying too hard.

Also on his watch, the Croton Aqueduct continued apace although its workers went on strike not once but twice in 1838 for better wages.

“The Great Embarrassment“

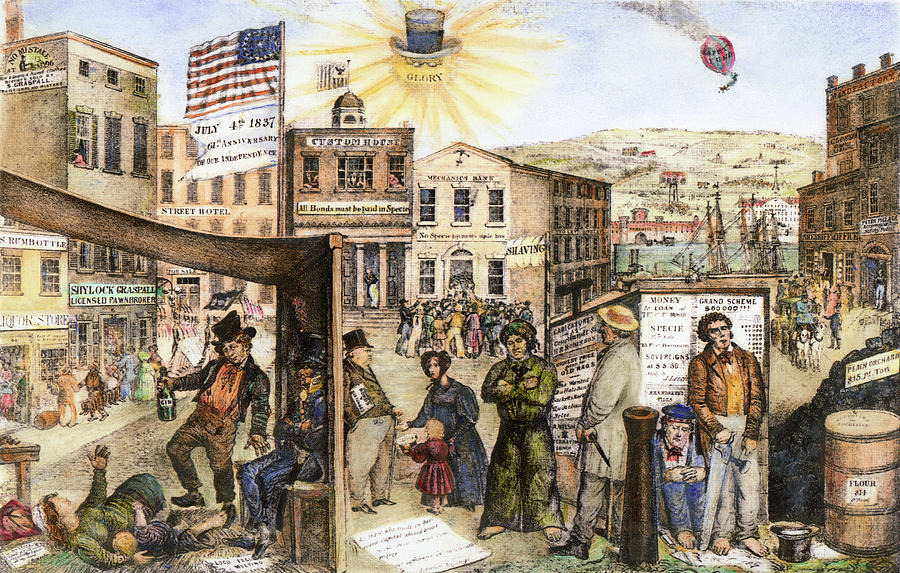

He also governed the city through the beginning of a grueling financial crisis, known today as the Panic of 1837.

Not even a month into Clark’s first term, on May 10, 1837, New York City banks ran out of gold and silver, having loaned out too much due to months of high inflation. President Jackson had hollowed out the central bank and refused to recharter it, leading to bank collapses across the country.

“During the Panic of 1837, approximately ten percent of U.S. workers were unemployed at any one time. Mobs in New York City raided warehouses to secure food to eat. Prominent businessmen, like Arthur Tappan, lost everything.” [source]

The Panic froze real estate developments across the city. Construction projects in Union Square and Gramercy Park sat unfinished.

“A deadly calm pervades this lately flourishing city,” wrote former mayor Philip Hone in his diary. “No goods are selling, no business stirring, no boxes encumber the sidewalks of Pearl Street.”

A Different Kind of Prize

It became clear that Clark was out of his depth. Two years of a Whig in office — with the tide of immigrants hardly abating — was quite enough.

In the election of 1839, Tammany put up Isaac Varian, who had been defeated the year previous by his political machine’s fractious split. Despite the usual cries of fraud, in this round Varian was the victor. Clark’s luck, if that’s ever what it was, had run out.

Clark left public life afterwards, dabbling in real estate and insurance enterprises, most notably becoming a supporter of Hamilton College in Clinton, New York. Since 1859, the school has presented an oratory prize in his name.

During its first year, The Clark Prize had eight competitors. “It is expected that the exercises will be unusually interesting and attractive,” claimed one article.

When Clark died in 1861, he was buried right here in the city, at the old New York Marble Cemetery in the East Village. The gates to this historic burial ground are occasionally opened to the public so I recommend bringing a lottery ticket to his headstone.