The South Street Seaport is the home for a great many nautical treasures. It’s also the location of a memorial to nautical tragedy.

The Titanic Memorial, a 60-foot white lighthouse, sits in the little plaza at Fulton and Water Streets.

This was no mere decorative lighthouse as it seems today.

For much of its history, it was an operational light source, a beacon over the East River.

The Titanic sank on April 15, 1912, killing more than 1,500 people from all social classes.

The loss shook society to its core. Among the victims were prominent New York businessmen and benefactors such as John Jacob Astor IV and Benjamin Guggenheim.

As New Yorkers mourned the loss of loved ones, they immediately funneled their grief into the building of memorials, the physical remembrance of a disaster that left virtually no trace behind.

Mayor William Jay Gaynor gathered community leaders to City Hall in May 1912 to solicit ambitious ideas of the new memorial.

The Evening World attributes one idea for a lighthouse to engineer Carroll Livingston Riker, who suggested “the lighthouse should be located at some perilous point on the coast, illuminated by a most powerful light and with a great fog horn that may be heard many miles as part of its equipment.”

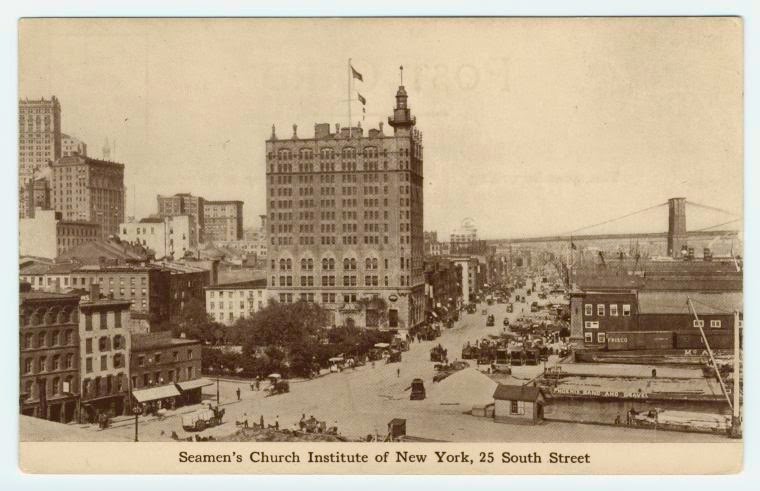

Meanwhile, a less dramatic lighthouse memorial (pictured above) was funded by J.P. Morgan and planned for the top of the new Seamen’s Church Institute at 25 South Street.

The lighthouse was equipped with a time ball which was lowered at noon to help distant sailors adjust their equipment. (This same sort of ball is affixed to the top of One Times Square in 1908, dropped every year at ring in the new year.)

The lighthouse memorial was dedicated on the first anniversary of the disaster with many family and friends of victims in attendance.

The New York Times claims the lighthouse and ball drop atop the Institute “were simply features of the existing plan, relabeled as a memorial.” [source]

However it became New York’s most prominent remembrance of the Titanic disaster after all when, over at City Hall, nobody could make up their mind on a truly grand memorial. (All you need to know about the city’s failed efforts is illustrated in this 1912 headline on one meeting — “One Man Made 18 Speeches.”)

Meanwhile, there were other Titanic memorials being planned in other parts of the city.

In Greenwich Village, in the Washington Square studios of Gertrude Vanderbilt Whitney, the artist began work on a sculpture for a national memorial in Washington D.C.

She displayed a model for the memorial in February 1916 that drew gasps from society women.

“[T]he present figure with its pedestal extends from floor to ceiling and catches interesting lights that add to the highly dramatic conceptions.” [source]

Whitney’s triumphant statue –of a figure with arms outstretched (not unlike Kate Winslet’s pose in the film Titanic) — was completed in 1918 but not installed in Washington until 1930 due to waterfront construction delays.

Yet another Titanic memorial was planned in June 1912 to honor philanthropists Isador and Ida Straus near their home on the Upper West Side. A competition was held in 1913 for aspiring sculptors, with Augustus Lukeman’s pondering nymph the eventual winner.

The statue and the newly named Straus Park were formally dedicated on April 15, 1915.

Featured at the dedication ceremony were 800 children who had been helped by Straus’ Educational Alliance on the Lower East Side.

Below: Dedication of Straus Square and its curious monument. (Courtesy Library of Congress)

As for the Titanic Lighthouse Memorial?

It sat dutifully atop the Seamen’s Institute for decades, its green light a welcome beacon to those entering the harbor.

By the 1950s, shipping no longer came through the area of New York’s waterfront, and the Institute eventually sold its building.

The lighthouse was donated to the South Street Seaport Museum in 1968, then a budding institution formed just a couple years prior to protect the historic structures of the area.

For a time, the lighthouse actually sat on the waterfront before relocating back to its present home in 1976, in a park partially funded by Exxon Oil.

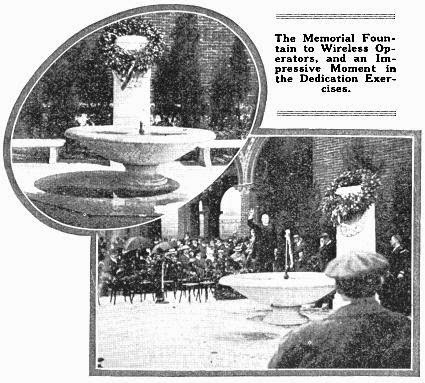

There was one other memorial to the Titanic disaster — the Wireless Operators Memorial at Battery Park. This bronze cenotaph and fountain was dedicated in 1915 to nine intrepid employees — “wireless heroes” — who died on the Titanic and in other ocean disasters.

Wrote J. Andrew White in 1915: “It is an eloquent reminder of a tradition that has grown out of the brand of courage which seeks no precedent, which, founded on the heroic action of a mere boy, has been written in the indelible annals of the men who go down to the sea in ships.”

After sitting in storage for many years, the memorial can once again be found in Battery Park.

1 reply on “A short history of New York City’s various Titanic memorials”

There is also a memorial plaque in Macy’s for the Straus.’ Enter the main entrance with the gold clock (across from Target) on 34th street. It was repainted a few years ago with a shiny gold paint. Let me know if you’d like some pics of the before/after. Would be happy to share with you.