HISTORY BEHIND THE SCENE What’s the real story behind that historical scene from your favorite TV show or feature film? A semi-regular feature on the Bowery Boys website, I’ll be reviving this series as we follow along with TNT’s limited series The Alienist. Look for other articles here about other historically themed television shows (Mad Men, The Knick, The Deuce, Boardwalk Empire and Copper). And follow along with the Bowery Boys on Twitter at @boweryboys for more historical context of your favorite shows. See the bottom of this article for more information on how to watch more episodes of The Alienist.

The Alienist begins — as it does in Caleb Carr‘s best-seller — with a bizarre and gruesome discovery one frozen evening in 1896: the violently mutilated body of a young man.

New Yorkers occasionally found such nasty sights along the waterfront; drunken sailors fell from their ships from time to time. But these human remains were seemingly displayed, laid upon “an elaborate maze of steel supports,” adjacent to the old creaking seaport.

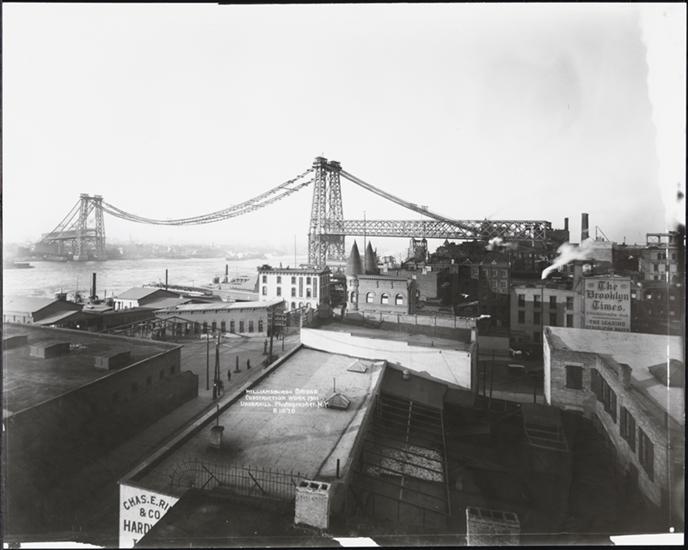

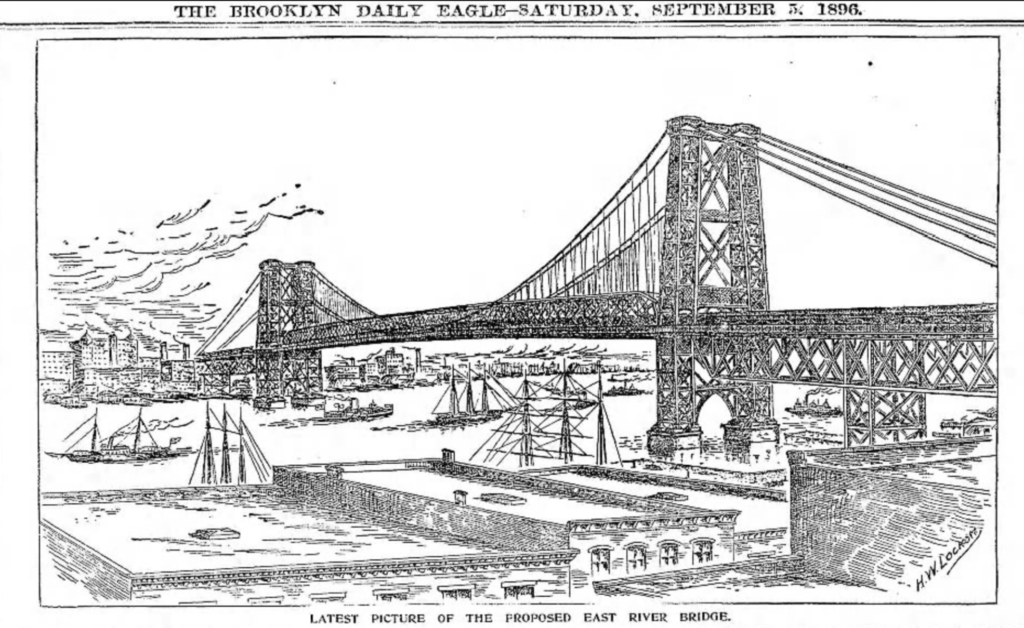

The supports depicted in this scene were but the first steps in the construction of one of New York’s last great engineering projects of the 19th century — the New East River Bridge a.k.a the Williamsburg Bridge.

This bridge, the second to ever span the East River, is truly under appreciated, dwarfed of course in architectural achievement by the first — the Brooklyn Bridge. But the start of its construction in the waning months of 1896 marked a bold and exciting turning point for the city of New York.

Here’s some details about the bridge:

— The bridge that would be called the Williamsburg Bridge was started (in 1896) when Brooklyn was an independent city and completed (in 1903) when Brooklyn was part of Greater New York. When it opened in 1883, the Brooklyn Bridge linked two of America’s biggest cities — New York and Brooklyn.

But city planners like Andrew Haswell Green hoped to unite the entire region as one thriving metropolis, sharing vital resources.

Despite great resistance by many powerful Brooklynites, plans to unite the two cities — along with areas of Queens County, Richmond County (Staten Island) and portions of Westchester County (the Bronx) — were well in place by 1896. By January 1, 1898, it would all officially become Greater New York.

(For more information, listen to our podcast on the story of the Consolidation of 1898.)

— But technically it was a bridge to yet another former city — Williamsburgh. In 1883, the Brooklyn Bridge linked the heart of New York civic life with the center of the City of Brooklyn — from New York City Hall to Brooklyn City Hall (what became Brooklyn Borough Hall). Upon its wildly successful opening, many began plotting a second bridge across the East River.

This second bridge, however, would link an area of Brooklyn north of the city’s center — in an area called the Eastern District.

Why was the eastern section of Brooklyn considered apart from the rest? Because at one point, for a brief period between 1852 to 1855, Williamsburg (or Williamsburgh, see below) was its own city, comprised of the modern neighborhoods of Williamsburg and Greenpoint. In 1855 it was absorbed — along with the Town of Bushwick — into the expanding city of Brooklyn and these new additions, more industrial and immigrant in nature, were referred to as the Eastern District.

(For more information, listen to our podcast on the history of Greenpoint, Brooklyn.)

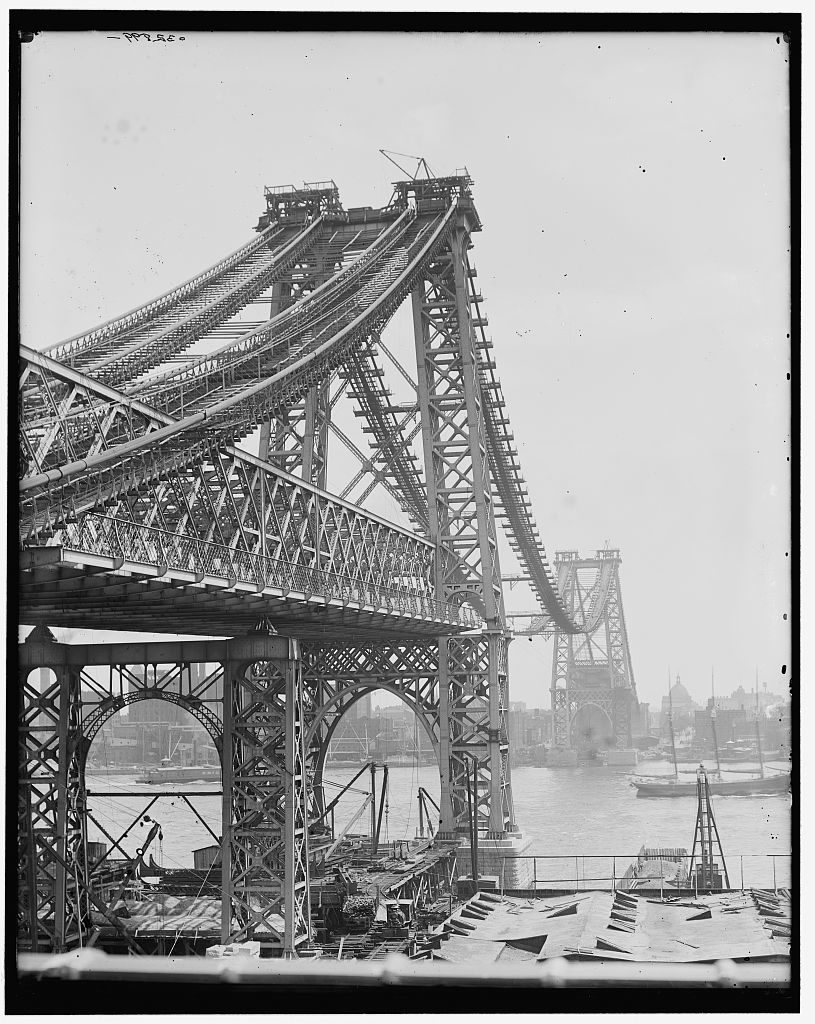

Below: Above the East River, the bridge under construction, 1900

— Brooklyn could thank one very powerful politician for the bridge. The namesake of Williamsburg’s popular McCarran Park — State Senator Patrick McCarran — is largely responsible for getting the new bridge placed in the Eastern District on the Williamsburg waterfront. According to one glowing eulogy, “The bridges, the parks, the improved means of transit, the better paved and lighted streets by which the Brooklyn of to-day is distinguished are due more to the legislative efficiency of Senator McCarren than to the influence of any other individual.” Of course he was also a bit of a corrupt scoundrel, but weren’t most politicians just a little bit dirty back then?

(Check out my article on rascally Mr. McCarren for more information.)

— Excuse me, that’s the Williamsburgh Bridge (with an H) The original village of Williamsburgh was named after the esteemed Lt Col. Jonathan Williams, former Secretary of War and grand-nephew of Benjamin Franklin, who surveyed the land along the Bushwick shore. In its early days there was an H affixed to the area’s name, but by the completion of the bridge in 1903, many references to the neighborhood dropped it. Nobody really knows why this happened, but it probably has something to do with the better known Williamsburg in Virginia.

By the time the bridge was completed, it was commonly known as the Williamsburg Bridge although a plaque on the bridge preserves the original spelling.

— On the New York side, planners were using the project as a way to clear away one of its most notorious districts –Corlears Hook.

Where Manhattan juts the furthest into the East River, Corlears Hook once had the greatest concentration of shipbuilding businesses in the nation, and the shoreline was completely obscured with piers, ships, and vessels of all sorts. In the 1830s, it had become a notorious red-light district, with “ladies of the night” setting up shop in the neighborhood’s saloons and cellars. (As popular legend would have it, the ladies of the Hook would give the oldest profession a new name: hookers.)

But by the 1880s, however, New York was in the throes of civic reform, clearing away slum neighborhoods and replacing them with parks or grand architectural projects. The old neighborhood of Five Points became Columbus Park and New York’s Civic Center. Even the Brooklyn Bridge cleared away the decrepit tenements of the old waterfront.

— The bridge is central to the growth of New York’s immigrant (and particularly Jewish) communities. While its construction did displace thousands of people, the bridge would actually facilitate better living conditions for Lower East Side immigrant groups by encouraging migration to less populated Brooklyn neighborhoods.

The New York Herald even called it the “Jews Highway” as those of Eastern European and Russian Jewish heritage transplanted to Williamsburg.

Below: Jewish women praying on the Williamsburg Bridge (1909)

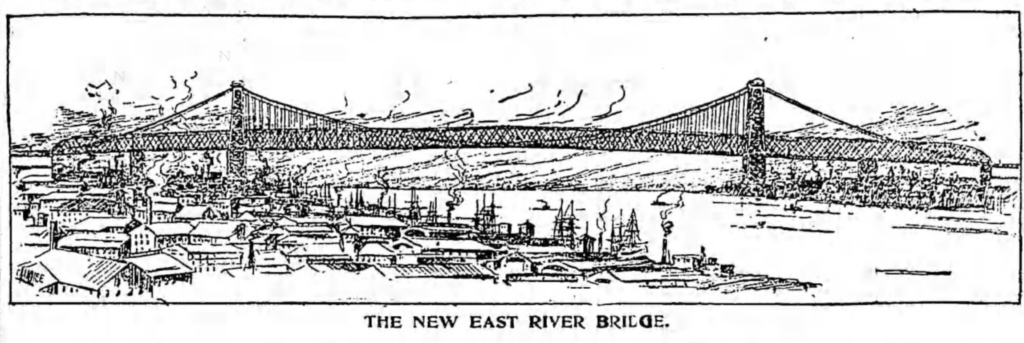

How they envisioned the bridge in the fall of 1896 ….

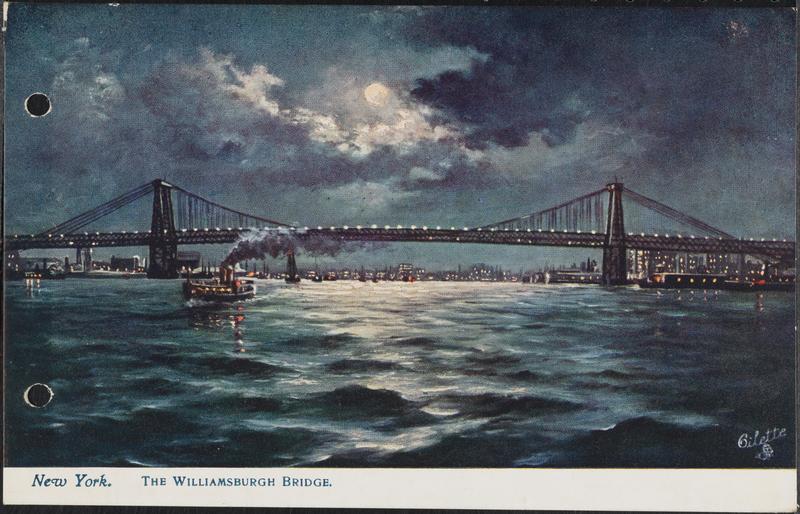

…and how it looked at completion.

Believe it or not, the opening of the Williamsburg Bridge was actually captured on film by the Edison company.

2 replies on “The Construction of the Williamsburg Bridge — History Behind the Scene (The Alienist)”

[…] https://www.structuremag.org/?p=10998 https://newyorkled.com/williamsburg-bridge/ https://www.boweryboyshistory.com/2018/01/construction-williamsburg-bridge-history-behind-scene-alie… […]

Sincerely,

Emperor Haile Selassie I