Jimmy Walker, Hollywood version of a mayor

KNOW YOUR MAYORS Our modest little series about some of the greatest, notorious, most important, even most useless, mayors of New York City. Other entrants in our mayoral survey can be found here.

In office: 1926-1932

Has a New York mayor ever reflected the decade he governed more perfectly than Jimmy Walker? Although John Hylan was actually the 1920s more effective mayor, it was Walker who embodied the Jazz Age spirit in his style, and the tragic Depression-era change of fortune in his downfall. He glamours us today because he’s both movie star and rebel; but the corruption of his regime is equally as striking and even disturbing in its grandiosity.

Walker is easily one of the most notorious mayors of New York, but today we can appreciate his brashness, his independence and class, just as we can lament his subservience to diabolic Tammany-era politics. He wasn’t the last disgraced mayor the city would see in the 20th century, but his abdication neatly defines the modern era’s defining fall from grace.

Jimmy, born June 19, 1881, was a New York boy and a golden one at that, raised in Greenwich Village among the bohemians, the son of an Irish immigrant who became a well connected Democratic assemblyman. Walker’s first passion seems to be music; in 1905 he stormed Tin Pan Alley writing songs such as “There’s Music In The Rustle Of A Skirt” and “Will You Love Me in December As You Do in May?” with its melancholy refrain:

Will you love me in December as do in May,

Will you love in the good old fashioned way?

When my hair has all turned gray,

Will you kiss me then, and say,

That you love me in December as do in May?

Below: In an odd ceremony with the mayor of Albuquerque

He had even less hesitation in announcing a political career, especially as Father had connections to a certain Al Smith, governor of New York. An adopted son of Tammany Hall, elected first to the state assembly in 1910 then to the state senate in 1914, young Walker sought Smith’s guidance and the governor soon took a fancy to the smooth, impeccably dressed young man, who shone like a new penny on the Senate floor. As he was described by Robert Caro:

“Pinch-waisted, one-button suit, slenderest of cravats, a shirt from a collection of hundreds, pearl-gray spats buttoned around silk-hosed ankles, toes of the toothpick shoes peeking out from the spats polished to a gleam. Pixie smile, the ‘vivacity of a song and dance man,’ a charm that made him arrive n the Senate Chamber like a glad breeze’ The Prince Charming of Politics…..slicing through the ponderous arguments of the ponderous men who sat around him with a wit that flashed like a rapier. Beau James.”

Smith took him under wing, maneuvering him through the entanglements of state politics, shielding Walker when his excesses got the better of him. He was a philandering cad and a boozer, even then. When opportunity arose to challenge the successful John Hylan for mayor of New York, Smith wanted Walker to run, but only if he would change his ways. Walker changed them all right; instead of partying out at speakeasies with chorus girls, he moved the whole production to a private penthouse funded by Tammany favors.

That election in 1925 was fierce. First, Smith had to dispense of Hylan in the Democratic primary — and in the halls of Tammany. The two split the storied political machine, but eventually Walker won out. Next, he faced the Republican-Fusion candidate Frank Waterman in the general election, who cried of potential Tammany corruption to the new subway system if Walker were elected. (Waterman would, of course, be right.) Beau James, however, went unabated. He ran as a people’s mayor, somebody who enjoys and the same pleasures as those voting for him:

“I like the company of my fellow human beings. I like the theatre and am devoted to healthy outdoor sports. Because I like these things, I have reflected my attitude in some of my legislation I have sponsored — 2.75 percent beer, Sunday baseball, Sunday movies, and legalized boxing. But let me allay any fear there may be that, because I believe in personal liberty, wholesome amusement and healthy professional sport, I will countenance for a moment any indecency or vice in New York.”

Right! Walker was one of the people. Everybody bought it but nobody believed it. He swept into office because New York, in 1925, was prosperous, a Jazz Age mayor for a Jazz Age city.

Once elected, of course, Walker countenanced all sorts of indecency and vice. He was frequently in Europe on vacation. When he was in town, it was rarely at City Hall. The lavish new Casino nightclub in Central Park became his unofficial headquarters, with Ziegfield dancer Betty Compton at his side. (Walker’s wife was out of town, frequently.) City business was often discussed with the pop of champagne cork.

Some things got done that first term: the New York hospital system was consolidated on his watch, he purchased thousands of acres for park land (including Great Kills in Staten Island), and grew the municipal bus system — greatly benefiting more than a few friends who happened to own the bus company given the exclusive franchise.

He managed to turn on his old ally the governor, scrubbing City Hall of any Smith loyalists, granting more jobs to his type of Tammany men, filling their own pockets but allied to the charming man in charge.

How did he stay so popular? This was the late ’20s and people wanted the mayor to reflect prosperity and confidence. He also gave back, in symbolic gestures. Even as the new subway system became clogged with corruption, he staved off a strike while keeping the fare at five cents, thought at the time to be an incredible concession.

He easily won election in 1929 against a largely outmatched Fiorello LaGuardia. Tammany was in place and unstoppable; but the voters still chose not to look askance at Walker’s dalliances, and even the newspapers were charmed. The New York Times wrote of his “great personal charm, his talent for friendship, his broad sympathies embracing all sorts of conditions of men,” then recommended him under the guise that “the Mayor that he has been gives only a hint of the Mayor that he might be.”

That hinted-at mayor never materialized, because the Stock Market crash did, plunging the city’s fortunes into ruin and exposing the weaknesses of a government consumed with greed. Suddenly, having an extravagant, indecent mayor didn’t seem like such a good idea.

Archbishop of New York Cardinal Hayes, once dazzled, now condemned the mayor’s amoral ways, opening the flood doors for others to lay the city’s problems was Walker’s feet. Eventually the accusations reached the ear of governor Franklin D. Roosevelt.

A commission lead by Justice Samuel Seabury exposed deep veins of corruption throughout the city’s legal system and police force. Innocent citizens, often women, would be charged with crimes and forced to pay steep fines to get out of jail time. (Many times they couldn’t pay, and off they went, dozens at a time.) Neighborhoods, most often Harlem, would be routinely raided and its residents taken in, wild charges conjured for maximum penalty.

This would line the pockets of dozens of judges and vice squad officers. Newspapers dubbed it the Tin Box Parade, “after one testified that he had found $360,000 in his home in a ‘tin box…a wonderful tin box'” (Caro).

Walker himself was brought to the stand to testify, the judge warning those in the court room not to look the mayor in the eye, lest they succumb to Walker’s sensational charm.

After months of epic battles on the stand — Walker eluding hot button questions about his personal bank accounts, delaying appearances until after Roosevelt’s nomination for president was assured — the embattled mayor could fight no longer. With Roosevelt mere months from his national election, he needed to be rid of Walker. Walker obliged in the classiest way possible: he resigned on September 1, 1932, and went on a grand tour of Europe with his Ziegfeld girl.

He was never charged with a crime. He was barely even held accountable for anything. Back in New York three years later, he held a series of smaller posts, including one for the New York garment industry that was assigned to him by new mayor LaGuardia, his former rival.

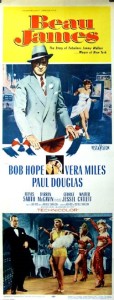

Nothing stuck to him. He died in November 1946 of a brain hemorrhage, just two years after returning to his first love as the head of a big-band record label with a stable of artists that included Louis Prima and Bud Freeman. Ten years later, Hollywood decided to do something very redundant and make a movie of his life, starring Bob Hope as Beau James. It would follow a screenplay only slightly less glamorous than the real thing.

15 replies on “Mayor Jimmy Walker: a finer class of corruption”

just want to let you guys know that your site is really appreciated as it is way cool to read your items that are posted.

how i wish i could afford to live in a Manhattan hi-rise and watch the world go by in the center of the universe that is NYC!

Jimmy Walker was also known as “The Midnight Mayor” for his predilection for nocturnal governance. He changed one of the eastbound streets in the East 60s to westbound so he could get to one of his haunts without the necessity of having to make a turn which would have interrupted his journey by a few minutes.

PRWnyc

Mayor Walker gave my grandfather $100 when he was 11 yrs old after his father (my great grandfather) passed away. The money was used to support my great grandmother and his 4 siblings for 6 months. He also helped my grandfather get a job driving a milk truck and later delivering laundered aprons when he got his working papers.

I wonder why there are not so many books about Jimmy Walker.

Perhaps a more appropriate movie recommendation than BEAU JAMES would be THE NIGHT MAYOR (1932), starring Lee Tracy as a mayor clearly modeled on Walker.

Thanks. I will check that out. Jimmy Walker fascinates me.

My dad worked as an office boy for a downtown financial company. He was 16 years old in 1931 when his boss asked him if he wantd to earn some overtime. My dad lost his own father only the year before and was working to help his mom care for his 4 younger siblings; and his boss knew this and figured my dad could use the money. He was told to go home and tell his mom he would be working late and then to come back after 6 p.m. to get his dinner money, car fare and his assignment. The assignment was to deliver a cigar box that was closed with 7 rubber bands of various colors to a man at the Cotton Club in Harlem at 9 p.m. He was also given an envelope that he was to present at the door of the Cotton Club – this envelope had the name of the man he was to make the delivery to. He was not to open the envelope nor to open the cigar box or tamper with the rubber bands. My dad got to the Cotton Club at 9, handed the envelope to the gent at the door and found himself ushered to the table of Mayor Jimmie Walker. He gave Walker the cigar box and Walker gave my dad a $20 bill and told him he was a good fella. My dad made 5 such deliveries to Walker over the next few months. He always gave my grandmother the $20 bill, but she never believed him when he told her how he made the money, and always insisted that he was at the pool hall shooting pool with “gangsters”. My dad told me all about Cab Calloway’s orchestra and how gorgeous the Cotton Club girls were. He was a Brooklyn boy who took good care of his mom and brothers and sisters and grew to be a wonderful man who served his country, was wounded at St. Lo in NOrmandy, stayed married to my mom for 54 years and was the best dad my brother and me could have asked for. He gave me a love of history, old NYC, and Brooklyn – and used to laugh about how he was Jimmie Walker’s 16-year old bagman!

Very good story about Jimmy Walker. You’re lucky to have a dad who could, and did, tell you about the old days. Blessings on him.

Jimmy Walker always enjoyed a good drink(in the middle of prohibition no less).

One of the stories my mother told me was that when a broadway producer turned down my grandmother, Betty Compton(my maternal grandmother), for a part the producer found the street torn up in front of the theatre on opening nite!

When I was growing up in New York, many a time I would mention my grandfather and older people would remember him kindly.

My father was a lawyer connected with Tammany Hall. He died when I was 2 years old. My mother, being Irish, never talked much about him. I am intrigued by this era (late 1920’s, early 1930’s) in New York City and would be grateful to receive any newsletter or other information in this regard.

My father was Joseph T. Flynn

Betty Compton was not a Ziegfield Girl. Walker met her in 1926 when she appeared in Oh Kay! He left his wife for her in 1928 which was the date given in Allie Walker’s divorce petition. They took up residence in the Ritz Carlton and later the Mayfair. True that he was raised in the Village but hardly among bohemians. He was a graduate of Saint Joseph’s School then on Leroy Street and Xavier High School. His father a businessman and Alderman moved the family to Saint Luke’s Place.

Walker cast his vote at the 32 convention for Smith not FDR while his case was pending. It was Smith who soon after refused to permit Walker to resign and run again in the Special Election. In all probability he would have won. Two Democrats actually outpolled LaGuardia in the General. FDR entertained Walker in the White House but never Smith his implacable adversary. You shouldn’t make too much of Tammany. Both Smith and Walker were immensely popular elected officials. True they were leaders but had important independent connections and thus were not controlled by the Hall. Hyland, from Brooklyn, was never a member of Tammany and that was a reason Smith, preparing to run for President, wanted Walker in as Mayor. Walker of course delivered the City to Smith by a wide margin but not enough to carry the state which FDR on the same ticket won by 100,000 votes.

This is where the Democrats learned the importance of maintaining credible deniability – one of their guiding principles even today.

I was told that my maternal grandfather, Thomas Cassidy, was a boyhood friend of Jimmy Walker’s. He lived at 17 LeRoy Street, and Walker lived at 19 LeRoy. Unfortunately, there is no one left to confirm the story.