Today (April 30th) is the 230th anniversary of the inauguration of George Washington, sworn in atFederal Hallas the first President of the United States. It is also the 80th anniversary of the 1939 New York World’s Fair. That was not an accident.

The monumental events of America’s founding would be immortalized by the fair in some rather unusual ways 150 years later. Both April 30th events were occasions of great patriotic ceremony (and both even slightly kitschy) in their own ways.

April 1789

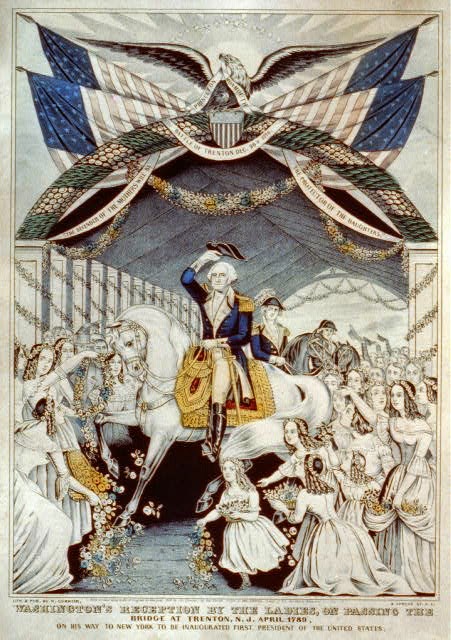

It took George seven entire days to get to New York from his home in Mount Vernon, as his procession was met every step of the way with throngs of patriotic crowds and flamboyant celebratory displays.

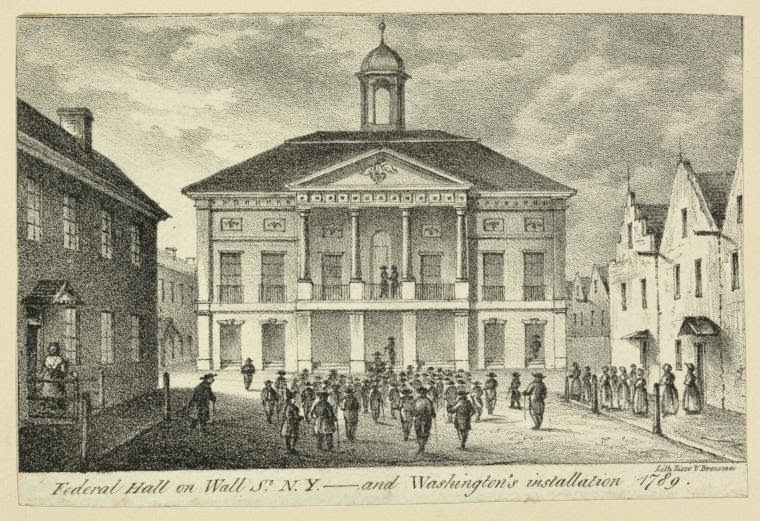

Washington’s vice president John Adams had already arrived in New York, on April 21st. The building which greeted him, the former City Hall building on Wall Street, had been the center of city’s government since 1699, when the British used materials from the city’s demolished north defense wall to construct it.

The heavily remodeled building which now stood in its place, later to be calledFederal Hall, was designed by successful city contractor and former Continental Army engineer Pierre Charles L’Enfant. According to author David McCullough, “it was the first building in America designed to exalt the national spirit, in what would come to be known as the Federal style.” (Sadly, this building was ripped down in 1812; the ‘Federal Hall’ which stands in the same spot today was built as a customs house in 1842.)

L’Enfant would later work on the creation of Washington DC out of Maryland swampland. He would ultimately be fired from that project — by George Washington.

George finally arrived in New York two days after Adams, April 23, via a barge from Elizabeth, New Jersey, and was met at the Wall Street pier by the current mayor of New York James Duane and the state’s governor George Clinton.

From there, he was taken to his new home on Cherry Street (long demolished, around near the Brooklyn Bridge anchorage today) and spent the day greeting dozens of well-wishers. That night, Governor Clinton hosted an elaborate dinner in his honor; the pomp and extravagance by this time were probably getting tiresome to the stately Virginian farmer.

Meanwhile Adams spent the week at Federal Hall in Senate chambers, hashing out such things we take for granted — such as how to even address the new president — until at last they were ready for the ceremony to begin, on April 30.

According to Ron Chernow: “Washington rose early, sprinkled powder in his hair, and prepared for his great day.” Like some detail from a fairy tale, Washington left his Cherry Street home at noon in a yellow carriage driven by white horses, legions of soldiers marching proudly behind him.

The streets of Manhattan were clogged with people, over ten thousand cramming Broad and Wall streets, as far as the eye could see both ways. Sitting on the balcony of his own home on Wall Street was Washington’s closest confidante Alexander Hamilton, certainly reveling in the moment.

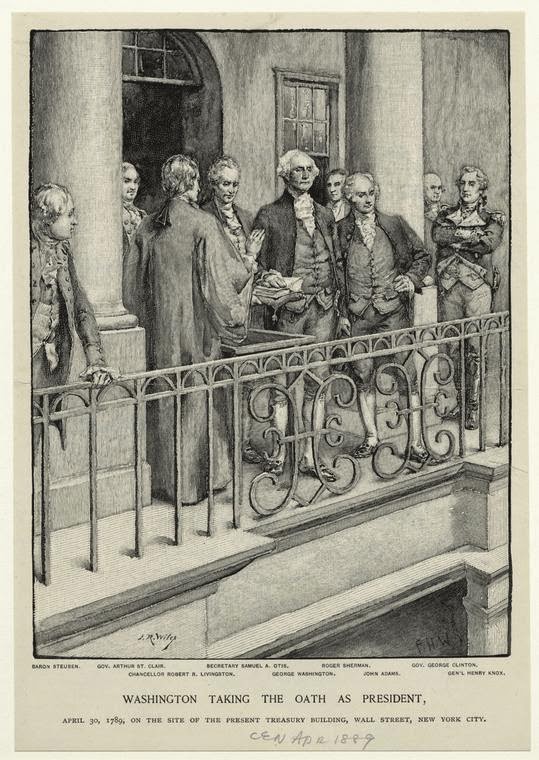

After greeting the Congress, Adams led Washington to the second floor balcony along with Robert Livingston, the Chancellor of New York (the highest judicial office in the state), who held out a bible owned by the St. John’s Lodge Freemasons and delivered the oath of office, probably not loud enough for anybody in the street to actually hear.

Washington, even less audibly than Livingston, swore to “faithfully execute the office of President of the United States, and will to the best of my ability, preserve, protect and defend the Constitution of the United States.” He then possibly threw in a ‘so help me God’ for good measure (although there are many doubts that this occurred).

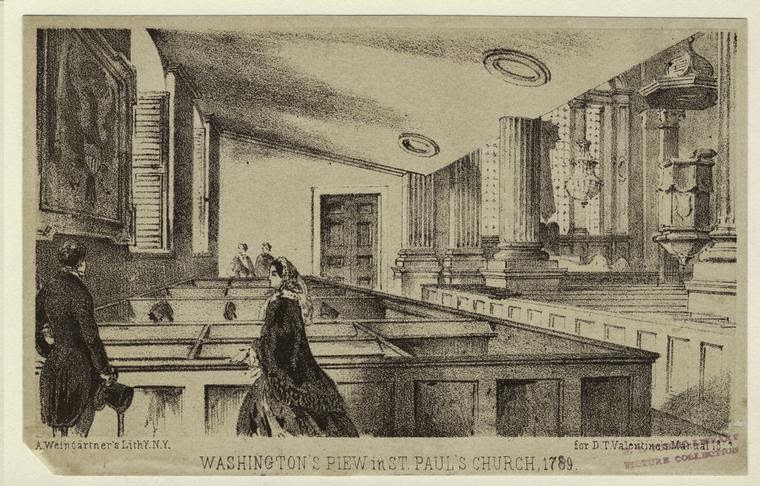

New Yorkers went crazy then, firing cannons, screaming and waving flags, playing music and dancing in the streets. After returning inside to address the new Congress — by this time with tears in his eyes — Washington and his entourage went up Broadway to receive on invocation at St. Paul’s Church, the scrappy survivor of the great fire the destroyed much of the city in 1776. Washington would be a regular here for his entire stay in New York; the pew where he planted himself for two years is still on display there (illustrated above).

Martha Washington would not arrive in town for another month, but that didn’t stop the parties. The official inauguration ball took place a week later, on May 7th, at the Assembly Rooms at 115 Broadway.

Although a bit stiff and silent, George was still popular with the ladies and danced “two cotillions and a minuet,” often seen with Alexander Hamilton’s young bride Eliza. When Martha arrived on May 17, landing at Peck Slip, she was greeted with similarly grand fanfare, and yet another ball was held in her honor.

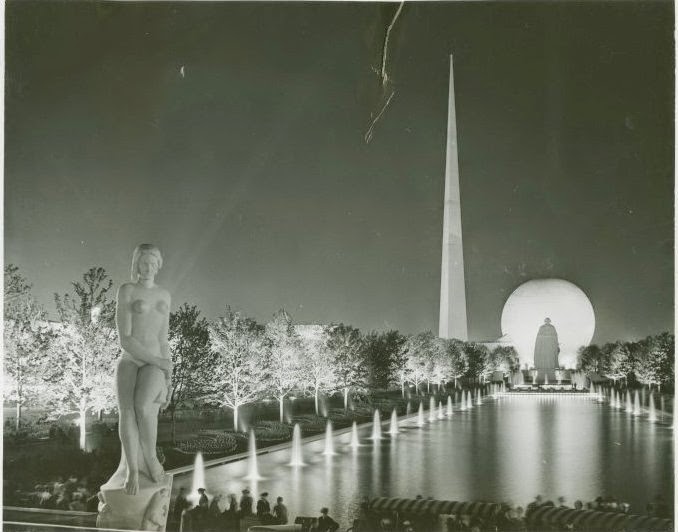

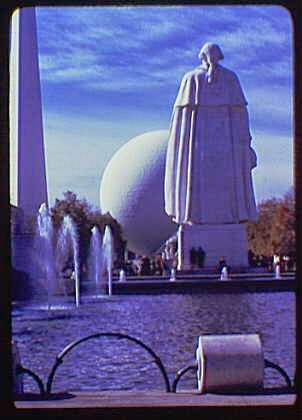

James Earle Fraser’s colossal Washington statue out in Queens. (NYPL)

April 1939

One hundred and fifty years later, the 1939 New York World’s Fair opened in Flushing Meadows-Corona Park, the second largest American fair up to that time (only St. Louis’ 1904 event was larger).

This celebration of human advancement — as demonstrated through miles of utopian kitsch and strikingly bizarre architecture — was a reason for Robert Moses to turn the unsightly Corona Ash Dumps into a Queens super-park. The fair was advertisement as entertainment, with hundreds of modern gadgets displayed as novelties and staples of the future.

But the celebration was planned with the past in mind as well. It opened on April 30, 1939, coinciding with another great day in New York City history — Washington’s inauguration. That’s how important the city thought the opening of the fair was. (Life Magazine was a little more cynical; in 1939, they refer to Washington as “the excuse” for the fair. The purpose, of course, was profits.)

A 61-foot-tall statue of Washington by James Earle Fraser stood mightily over the fair’s Constitution Mall, peering perhaps quizzically at Paul Manship’s massive sundial sculpture. A cluster of buildings called the Court of States recalled the Colonial architecture of Washington’s day. Even Federal Hall was recreated.

Below: The World’s Fair presented a recreation of Washington’s inauguration, except with lots of flag dancing. (NYPL)

A replica of Mount Vernon (sort of) called Washington Hall was the pet project of a New Yorker with presidential ties.

According to the New Yorker, “Mr. Messmore Kendall, is responsible for the Hall. Mr. Kendall, president of Sons of the American Revolution and owner of the Capitol Theatre, [developed] plans for erecting, entirely at his own expense, a $28,000 building to house a collection of Washington relics. Before the Fair closes, he expects the whole thing will have cost him more than $50,000. He has given more than money to the project; he has given the family cook, so that whenever he wants a home-cooked meal, he has to go all the hell out to Flushing.”

The Hall received a host of reenactors who had made their way up from Mount Vernon in emulation of Washington’s own footsteps. On May 6th, a child named Robert E, Lee Williamson opened Washington Hall in a grand ceremony, bringing “three consecutive weeks of neo-Federal quaintness to a close.” [source]

The president also sits (sometimes awkwardly) upon a variety of World’s Fair merchandise. Light shows and fireworks unheard of in Washington’s time were dedicated in his honor throughout the fair. He even starred in a popular musical pageant at the fair called American Jubilee, with books and lyrics by Oscar Hammerstein.

It was another great president who kicked off the fair 75 years ago. With 200,000 people in attendance, Franklin Delano Roosevelt gave an opening speech extolling the virtues of American ingenuity as he became the first president to be broadcast to television audiences. Few had televisions in their homes at the time. But NBC founder David Sarnoff helpfully scattered a few dozen of them throughout the city in a clever publicity stunt.

Roosevelt starts off his speech referencing Washington. “[T]here have been preserved for us many generations later, accounts of his taking of the oath of office on April thirtieth on the balcony of the old Federal Hall. ….. And so we, in New York, have a very personal connection with that thirtieth of April, one hundred and fifty years ago.” [Read the whole speech here.]

Defined by the odd Trylon and Perisphere buildings, the fair seems like something truly dreamlike. The land where the fair once stood now contains the ruins of a New York’s other World’s Fair, the event from 1964-65.

TODAY

You can still find a tribute to George Washington in Flushing Meadow Corona Park today. George Washington as Master Mason by Donald De Lue was installed here in 1967, a replica of a much larger Washington statute, made of plaster, that stood at the New York World’s Fair of 1964-65 within the Masonic Pavilion. (That’s right; the Freemasons had a World’s Fair pavilion).

That 11-foot plaster statue of Washington stood next to the actual Masonic Bible on which Washington took his oath of office. Today the bible is on display — at Federal Hall.

For this article, I’ve re-purposed a couple pieces of writing I did on these events a few years ago. The original pieces can be found here and here.

5 replies on “George Washington’s inauguration and the 1939 World’s Fair”

[…] the first president to cry publicly — that distinction actually goes to the first president. George Washington is said to have cried at his inauguration in […]

[…] the first president to cry publicly — that distinction actually goes to the first president. George Washington is said to have cried at his inauguration in […]

What was the 61 foot tall statue made of and was it saved after 1940?

The 65 foot tall statue of Washington was made of plaster. It is doubtful that the statue could be moved easily to another “permanent” location. I have not heard of it elsewhere.

[…] first chairwoman to yell publicly — that distinction actually goes to the first chairwoman. George Washingtonis said to have wept at his inauguration in […]