PART FIVE UPDATED BELOW – CONSOLIDATED CITY

See map below for all the locations mentioned in this story

One of the truly great podcast pleasures of the past two months has been the BBC’s A History of the World In 100 Objects, a daily chronological journey through human history via carefully selected items from the British Museum. Stone axes! Golden toothpicks! If you haven’t listened to it, give it a try, especially if you enjoy history conveyed through very proper British accents.

Since we’ve begun work on our 100th podcast (to be released on March 19th), I thought I’d take on a wacky experiment here on the blog, to try the same concept in charting New York City’s history, but using its bulkiest commodity — buildings.

Generally speaking, history is never kind to buildings. With a story filled with great fires, draft riots, urban renewal projects, terrorist attacks and greedy developers, New York City changes its landscape often, with financial downturns, community activism and landmark designations often the only forces stemming the tide.

But with a little creativity, it is possible to chart the city’s entire history from currently standing structures (or in certain cases, reconstructions of original buildings). These 100 buildings and complexes represent just my own perspective, based on my work here on the blog and the podcast. Another person could attempt this same task using a completely different list of buildings. This is not meant to be in anyway authoritative, just my opinion based on stuff I’m picked up thus far on this little trek through history.

There’ll be an update once a day (or so) so check back every day for more. At the bottom of this post will be a Google map of all the locations mentioned. Hopefully this will inspire you to visit a landmark you’ve never heard of or plan a self-guided walking tour around a favorite neighborhood

I’m crunching a lot of data here, so if you see any errors with dates or other information, just drop me a note here or at boweryboysnyc@earthlink.net. Also, if you have a favorite place to add, feel free to leave a note in the comments section. Hope you like it!

_______________________________________________________

PART ONE: NEW CITY  Photo courtesy Wyckoff Association

Photo courtesy Wyckoff Association

1 Wyckoff Farmhouse (Brooklyn)

In the beginning, there was the Pieter Claessen Wyckoff House (above). At least, that’s what the Landmarks Preservation Commission, borne of the destruction of old Penn Station, thought in 1965 when they named this modest saltbox frame abode the very first New York City landmark.

No traces outside of a museum exist of old New Amsterdam, but the mark of the Dutch farmers who came along for the ride are still with us. Pieter Claesen was granted this land directly from Wouter van Twiller after the director-general of New Amsterdam bought it from the Lenape inhabitants in the late 1630s. A few Dutch farmers had already ventured onto this wild patch by the time Claesen (who would take the surname Wyckoff after the British took over) built his farm here.

Part of the current structure is from this original home, built in 1652. Many changes came to the house over the years, but the Wyckoff family in some form stayed until 1901. It takes virtually little imagination to stand in front of his sturdy brown house and envision a open, wild Brooklyn landscape behind it.

2 John Bowne House (Queens)

Bowne’s house, in Flushing, is significant to me for one big reason: it was witness to Peter Stuyvesant. Or rather, his temper.

Quaker Englishman John Bowne and his family settled in Dutch territory mostly to escape the Puritanism of his former residence, Boston. No luck here however. Stuyvesant arrested for holding Quaker gatherings (wild, dangerous Quakerism!) in his home. Sent to Holland for trial, he was acquitted and came back to Flushing with a reprimand to Stuyvesant — a reinforcement of New Amsterdam’s religious tolerance.

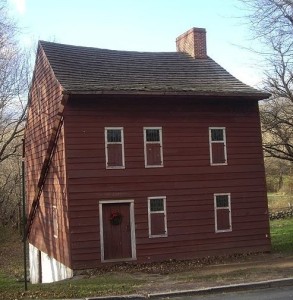

3 Voorlezer’s House (Staten Island) The transition from Dutch to British rule is easily seen in this simple two-story building (at right) in the vicinity of Historic Richmondtown. Built sometime between 1680 and 1696 by the Dutch Reformed Church, this home for a ‘voorlezer’ (reader and instructor) is considered the oldest elementary school in the United States. Despite British control over the newly named Richmond Country, society would still have leaned heavily Dutch-inspired for decades after.

The transition from Dutch to British rule is easily seen in this simple two-story building (at right) in the vicinity of Historic Richmondtown. Built sometime between 1680 and 1696 by the Dutch Reformed Church, this home for a ‘voorlezer’ (reader and instructor) is considered the oldest elementary school in the United States. Despite British control over the newly named Richmond Country, society would still have leaned heavily Dutch-inspired for decades after.

4 Conference House (Staten Island)

Although Richmond County was very pro-British by the 1760s, it was pulled into the conflict between the crown and American rebels by the island’s situation in New York harbor, across from rebellious New York. This home of Christopher Billopp, built in 1675, would take center stage in the conflict a hundred years later, when Continental Congress representatives John Adams, Benjamin Franklin, and Edward Rutledge met with British military to fend off an encroaching war. To no avail. Courtesy Old Stone House/NPS

Courtesy Old Stone House/NPS

5 Old Stone House (Brooklyn)

Within the month, British forces swept into Long Island, turning back George Washington’s men at every bend. Here at a simple stone farmhouse overlooking Gowanus Creek, Washington’s troops briefly rallied, holding the old house and firing against the British. “What brave men I must this day lose,” George reportedly said as he look down upon the beleaguered little building. (Pictured above in more bucolic times.)

This current house is actually a reconstruction from 1930 — using materials from an original Dutch home from 1699 — and it may be difficult to see redcoats whizzing by from its vantage near Park Slope.

6 Fraunces Tavern (Manhattan)

This too is a reconstruction of the original tavern which sat here, a key meeting point before, during and well after the Revolutionary conflict. Artifacts in the second-floor museum will give you a good idea of life in Colonial New York, but even having a drink in Fraunces’ darkened bar downstairs, one can envision hushed conversation from impassioned revolutionaries or perhaps a brawl between drunken British soldiers. Courtesy Jumel Terrace

Courtesy Jumel Terrace

7 Morris-Jumel Mansion (Manhattan)

The oldest home in Manhattan (1765) is pretty much how the other half lived; British colonel Roger Morris built this palatial estate well outside New York in tumbling, secluded hills and hosted his superiors here after they succeeded in rushing George Washington and his men out of Manhattan. (Washington himself even took over the home briefly on the army’s way out.)

Post-British era, the home’s dining room entertained many of our country’s founding fathers. However, its history only gets more absorbing when the house is purchased by merchant Stephen Jumel and his scandalous Eliza, who took up with Aaron Burr after Stephen’s mysterious death.

8 St. Paul’s Chapel (Manhattan)

This chapel (from 1766) is, in my humble opinion, New York’s greatest colonial landmark. Surviving the fire of 1776 which wiped clean most of New York’s early historic structures, St. Paul’s is the only true surviving witness of the years when the seat of federal government sat a few downs down at Federal hall. Alexander Hamilton trained as a soldier outside in the churchyard; Washington worshipped here as president of the new country. The chapel is such a symbol of fortitude that even during the Sept 11 attack in 2001, just blocks away, nary a window was even broken.

9 Fort Jay (Governor’s Island)

The current fort structure was built in 1806, but it was constructed over an original earth fortification used first by the Americans, then by the British during their occupation from late 1776-1783. One example of dozens of such primitive forts, now lost to redevelopment, the original placement of these early can be seen in the ripples of earth inside the fort. It was rebuilt in 1806 — and originally called Fort Columbus — and served as one of many harbor defenses. The fort held upper-tier Confederate officers during its years as a Civil War prison.

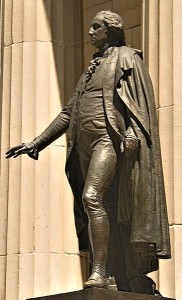

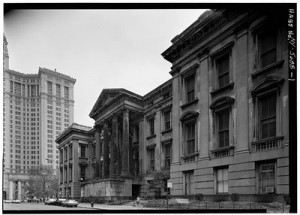

10 Federal Hall (Manhattan) Nothing exists of the original hall (demolished in 1812), so from the perspective of a chronological history, this building is disappointing. This current structure (1842) was New York’s original custom house, processing the flow of imports and exports into one of the busiest ports in the world. However it would revert to a shrine of the earlier Hall within a few decades; today, you cannot get a physical sense of the original building, but the museum inside and the lustrous 1882 Washington statue outside will give you a virtual sense of New York’s importance in 17th century Colonial America.

Nothing exists of the original hall (demolished in 1812), so from the perspective of a chronological history, this building is disappointing. This current structure (1842) was New York’s original custom house, processing the flow of imports and exports into one of the busiest ports in the world. However it would revert to a shrine of the earlier Hall within a few decades; today, you cannot get a physical sense of the original building, but the museum inside and the lustrous 1882 Washington statue outside will give you a virtual sense of New York’s importance in 17th century Colonial America.

For more information: try our two podcasts on the Revolutionary War (The British Invasion: New York 1776 and Life In British New York) or a listen to everybody’s favorite director-general, Peter Stuyvesant

_______________________________________________________

PART TWO: PORT CITY

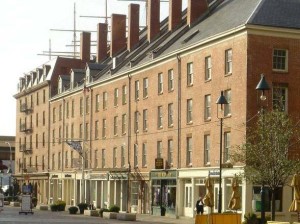

11 Schermerhorn Row (Manhattan)

After the war, New York flourished as an international port of commerce, the harbor filling with foreign merchandise to be distributed throughout the new country, the waterfront lined with boat slips all along from the bottom of Manhattan island up to South Street. With the opening of the Erie Canal in 1825, the floodgates of wealth opened further. Schermerhorn Row (1810-12) is one of the few remaining survivors of this early period of ship-based commerce.

In 1810, Uber-wealthy merchant Peter Schermerhorn began work on this row of plain storeroom buildings to lease out to prospective counting houses. They were north of the core merchant area, which saved them from destruction when the Great Fire of 1835 swept through lower Manhattan. They barely survived an even greater disaster — the 1970s — when they were given landmark status in 1977. A skyscraper stands just a few feet away to remind visitors of the alternative. Today the row of Federal Style buildings house the Seaport Museum and various shops and restaurants.

12 Castle Clinton (Manhattan)

New York’s preeminence as a port also made its residents understandably skittish about another invasion, and rumbles of another war with the British convinced New Yorkers to built fortifications all along the harbor. Although the events of the War of 1812 never quite made it to New York, the city was prepared, building Castle Williams on Governors Island, and out in the water right at the tip of Manhattan, Castle Clinton (1811), named for governor DeWitt Clinton.

The noble brown shell housing tourists today hints but slightly at its glory days as the grand performance hall Castle Garden, as New York’s pre-Ellis Island immigrant station, and, as a home for penguins and seals, the New York aquarium. Although not a shot was fired at the elderly fort, it still managed to survive its greatest villain, Robert Moses, in his quest to rip it down in the 1940s.

ALSO: On the opposite shoreline, the U.S. government builds the Brooklyn Navy Yard in 1806. Although you can’t go inside, you can sneak a peek at the gated, wonderfully out of place Commandants House (built 1805-6) in the neighborhood of Vinegar Hill.

13 Building C, Sailors Snug Harbor (Staten Island)

Perhaps the fact most greatly underscoring New York’s naval importance is the way in which the city honored and took care of its retired sailors and seamen. The Staten Island estate of Robert Richard Randall was transformed into a sumptuous retirement home, a quiet respite within sight of the harbor where many of its elderly residents spent their careers. The new Sailors Snug Harbor (above), opened in 1833, featured the greatest selection of Greek Revival architecture outside Washington D.C., with Building C (1831-33), the centerpiece, its most lavish survivor. 14 Archibald Gracie Mansion (Manhattan)

14 Archibald Gracie Mansion (Manhattan)

The kings of shipping, the new merchant princes, built their homes along the water as a testament to their growing wealth. Shipping tycoon Archibald Gracie plants his estate (at left) just north of the supposedly haunted Jones Wood in 1799. Although he had to later sell it to pay off debts, the rustic, Federal Style home later became the official mayor’s residence, from Fiorello LaGuardia to Rudy Guiliani (who moved out mid-term).

ALSO: On a small island strip in the East River, the island’s owner James Blackwell builds his home here in 1794, the oldest structure standing on today’s Roosevelt Island. Another house, the Hamilton Grange, is constructed in 1802 near on the Hudson River side of the island; its owner, Alexander Hamilton, would only enjoy it a few years before his untimely death.

15 St. Marks Church in-the-Bowery (Manhattan)

St. Marks Church (built 1799) stands on former farmland of Peter Stuyvesant, sitting at an angle next to tiny Stuyvesant Street — vestiges of the original lay out on the estate. The rest of Stuyvesant’s farm was carved up by the 1811 Commissioners Plan, a visionary work of urban planning, taking Manhattan island and mapping out hundreds of streets and avenues over land that was mostly undeveloped wilderness. The plan was so successful in creating uniformity that it’s difficult to envision the rambling disorder of streets before they were carved into need orderly rectangles. At St. Marks, you can take solace imagining the former layout while visiting the crypt of ole Stuyvesant (who might still be haunting here).

16 St. Patrick’s Old Cathedral (Manhattan)

An altogether different house of worship lower down the Bowery, St. Patrick’s (built 1809) catered to the lowest rung of New York society of the time — the first wave of Irish Catholic immigrants. St. Patrick’s (above) was often a church under siege; in 1835, anti-Catholic mobs stormed the place, its parishioners rushing to the chapel’s defense. The cathedral would become safe haven for different ethnics, most notably the growing Italian community at the start of the 20th century.

17 65 Mott Street (Manhattan)

In the 1820s, the area around St. Patrick’s was still considered the outskirts of town. With New York’s center becoming overcrowded, the poor clustered in communities of cheaply made structures. To the south of St. Pat’s, crumbling townhouses sinking into marshy land would soon give way to the darkened slums of the Five Points neighborhood.

These homes would be refitted for multiple families. Constructed in 1824, the plain structure (by today’s standards) at 65 Mott Street would become the first specifically made for multiple tenants — the first tenement building. Within years, these tenements would become the standard style of living, each packed with hundreds of poorer residents.

18 Washington Square North 1-3 (Manhattan)

Not everybody lived this way naturally. The poor may have had little choice where to live. But wealthier New Yorkers could venture further north and west, and when yellow fever epidemics made cramped urban living unsafe, many ventured to newly affordable plots in the area of Greenwich Village.

When the city landscaped the new Washington Square Park in 1826, it naturally attracted the wealthiest of New Yorkers, who built row houses along its northern rim. The oldest surviving buildings here, 1-3 Washington Square North (built in 1833), would be iconic representations of early American comfort, over the decades becoming home to well-connected families, dignitaries and artists. And they would kick off the triumphal upper-crust procession up Fifth Avenue.

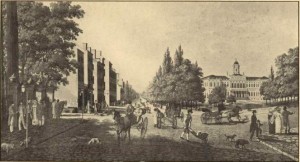

ALSO: For some visitable interiors, you can get a fuller sense of how ‘the other half’ lived further east at the Merchant House Museum (1832). The even older building at 326 Spring Street — known as the James Brown House, (1817) — was a former boardinghouse and home to Brown, an ex-slave Revolutionary War hero. Today, you can delight in its history while having a beer as the Ear Inn, its incarnation since the 1970s. City Hall and environs in 1820

City Hall and environs in 1820

19 City Hall (Manhattan)

With great fanfare, city leaders decided to move city offices from Federal Hall on Wall Street up to a new structure built on a worn patch of public ground up north on Broadway. The new building, completed in 1812, reflected the popular feeling of the day; the northern side, facing up the island to a drained Collect Pond, scattered lower class developments, was originally constructed with less quality materials.

City Hall would survive fires, renovations and corrupt administrations to remain the oldest, continuously operating center of city government in the United States.

20 24 Middagh Street, ‘Queen of Brooklyn Heights’ (Brooklyn)

Meanwhile, across the river, speculators were beginning to lure New Yorkers over to the small town of Brooklyn, with spectacular views and a brand spanking new Fulton Ferry service (which began operating in 1814). Within a few years, the first developments would pop up on the bluff later to be called Brooklyn Heights.

The area’s oldest structure, the home built by Eugene Boisselet at 24 Middagh Street (1824), is considered the ‘queen of Brooklyn Heights’. Its woodframe Federal Style glamour are a sharp contrast to the great brownstones that would define the neighborhood many years later. The ‘queen’ would quickly find herself surrounded as the area became popular with eager New York escapees, the first commuters. But not every area of Brooklyn was quite ready to urbanize….

21 Flatbush Dutch Reformed Church (Brooklyn)

The rest of Brooklyn would earn its reputation as a ‘City of Churches’ with buildings like Flatbush’s fine old chapel, completed between 1792-8.

The third church in this very spot — the first sanctioned by Mr. Stuyvesant himself in 1654 — the dark stone chapel held together a quiet, bucolic Long Island farming community, removed from the bustle of the harbor. The independent town of Flatbush, one of six in Kings County, contrasted sharply with Brooklyn and would retain its autonomy from that growing city for most of the century.

For more information: try our podcasts on DeWitt Clinton, Collect Pond, Washington Square, Green-Wood Cemetery (for a brief history of Brooklyn Heights), St. Patrick’s Old Cathedral, Castle Clinton and New York City Hall _______________________________________________________

PART THREE: INDUSTRIAL CITY

22 Lorillard Snuff Mill (Bronx)Throw a rock in the Bronx before 1840, and you’re likely to hit a cow. However, being north of Manhattan, it was only a matter of time before its uninterrupted stretches of farmland were soon met with change. Before the 1840s, it was nothing but cows, wheat fields, and the occasional estate (see below). But the industrial progress of New York soon began to seep into this future borough, and the advent of the railroad and the rise of immigration began to turn the tide for this agrarian outskirt.

The Lorillard tobacco manufacturer, who got their start in Manhattan back in 1760, built its snuff mill here (above( in a Bronx riverbed, using water power to meet up with the growing demand of homegrown tobacco. It’s one of the oldest surviving examples of early American industry. Today, you can find it nestled in the New York Botanical Garden — and currently undergoing renovation.

23 Wave Hill House (Bronx)

Another Bronx landmark of the period has also succumbed to flowering beauty. Wave Hill represents one of the best preserved examples of homes overlooking the Hudson River still within the city today, a modern rarity from a period of dozens of cliffside homes. Lawyer William Lewis Morris, from a family of wealthy Bronx landowners, built his Victorian estate (1843) as a summer retreat; later, the house (below) would entertain the likes of Mark Twain and a young Theodore Roosevelt. The city took it over in the 1960s, and today its a public garden with its breathtaking views intact.

ALSO: Ten years later, railroad magnate Edwin Clark Litchfield had his equally impressive and quite curious Italian-style home, Litchfield Villa, erected on land later bought for Prospect Park.

Below: Wave Hill House, in one of the most beautiful spots in the Bronx

24 Hunterfly Road Houses (Brooklyn)

Slavery was abolished in New York state in 1827, but in practice, black city residents had few of the property rights as their white neighbors. The African-American settlement of Seneca Village was eradicated by the creation of Central Park, and blacks were not welcome in many New York neighborhoods.

But evidence of a seven-block African-American development in Brooklyn still exists at 1698 Bergen Street, the remains of the settlement of Weeksville, a small neighborhood developed (1840) by a black developer for black residences, “the second largest known independent African American community in pre-Civil War America”, according to the Weeksville Heritage Center.

25 Trinity Church (Manhattan)

The tallest building in New York (from its creation in 1846 to 1890) with the wealthiest most power congregants, the third Trinity on this spot would be defining symbol upon a growing New York skyline. Even without the fabulous Richard Upjohn design, the church would remain the city’s most powerful landlord. But it always helps to look good.

ALSO: The uptown Grace Church, consecrated the same year, would grow in prominence as high society began moving up the island. If you weren’t a member of a powerful family, don’t bother looking for a pew. 26 Beth Hamedrash Hagadol (Manhattan)

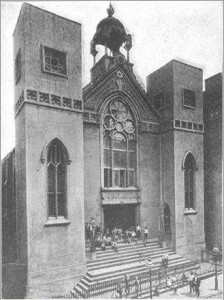

26 Beth Hamedrash Hagadol (Manhattan)

The Lower East Side’s oldest synagogue (1850) is the most spectacular reflection of the neighborhood’s changes of the period, as immigrants from Europe crammed into affordable tenements. Within a few years, the new residents would turn this stretch of land below Houston into the most concentrated Jewish community on earth.

ALSO: Beth Hamedrash is the oldest, but the close-by Eldridge Street Synagogue (1886-7) is probably the most beautiful

27 India House/1 Hanover Square (Manhattan)

Further downtown, New York cleans up from the great fire of 1835 and resumes business. Hanover Square had been a center for publishing and retail since the British days; in the flourishing New York economy, it became an extension of Wall Street with banks and exchanges.

The India House (1851-53) became both — first as Hanover Bank when it was built, then as the first commodity market in 1870 (the New York Cotton Exchange). Given the fervor for skyscrapers in the region, it’s a wonder this great example of mid-19th century commerce still exists.

28 Cooper Union (Manhattan)

In the right people, economic power and growing population breeds benevolence. Inventor and philanthropist Peter Cooper created Cooper Union (1853-59) as a place for free education — to both men and women. In construction of this brownstone Astor Place anchor, he also provided one of the great auditoriums of the city, which a year hosted a young politician named Abraham Lincoln.

29 Smallpox Hospital (Roosevelt Island)

Sometimes though, economic power and a growing population breeds, well, indifference. New York is best known for putting its undesirables on islands, and in defining those undesirables rather broadly — criminals, orphans, delinquents, infirm, diseased, or just really poor.

Blackwell’s Island was the most notorious of these, although nearly all of New York’s islands have enjoyed their shares of hospitals and prisons. The ruins of James Renwick’s Smallpox Hospital (1856) are a vivid reminder. 30 Engine Company 204, Cobble Hill (Brooklyn)

30 Engine Company 204, Cobble Hill (Brooklyn)

As soon as they put stuff up, it was burning down. New York, Brooklyn and the surrounding cities and towns were under constant threat for fire. As a result, in the years before paid firefighting services, the methods became territorial, with competing gang-controlled fire operations. Fighting fire was less a community service than a sign of sporting-man machismo.

There are excellent architectural examples of still-operating 19th century firehouses throughout the city. The one at 299 Degraw Street in Cobble Hill is not one of them. However, it is the oldest firehouse that I can locate, built in 1855 for the volunteer Montauk Hose Company in the years before Brooklyn had an organized firefighting unit. This structure held the horses; the volunteers slept across the street. After a valiant community effort to save the company, the city decommissioned the building.

ALSO: If you prefer an active firehouse, try Engine Company No. 5 at 340 East 14th Street in Manhattan, designed by Napoleon LeBron in 1880.

31 Plymouth Church (Brooklyn)

Another kind of fire was stirring at the center of Brooklyn high society — Plymouth Church (1849-50). By 1854, Brooklyn had absorbed Williamsburg and Bushwick to become the third largest city in the United States. Its preeminence was embodied by Plymouth’s fiery celebrity preacher Henry Ward Beecher, who was Brooklyn’s defining voice even after scandal knocked him from the podium in the 1870s.

32 Tweed Courthouse (Manhattan)

But if it’s scandal you’re looking for, look no further than the exploits of Boss Tweed and his corrupt political machine Tammany Hall. Nothing embodies the excess and wastefulness of Tammany graft than the courthouse unofficially named for the man who kept it filling its contractors’ pockets with money. Taking twenty years to build (1861-1881), it’s one of the most expensive buildings ever built in the 19th century. Courtesy Flickr

Courtesy Flickr

33 Fort Schuyler (Bronx)

New York’s participation in the Civil War was more than just that pitiful and deadly distraction known as the Draft Riots. New York residents became soldiers, financiers, supporters and critics of the conflict. The city played a more direct role as a holding station and hospital base for thousands of militia. Fort Schuyler, began in 1833 and not fully dedicated until 1856, held hundreds of Confederate soldiers and housed thousands more Union troops on their way to battle. Today students wage for battle here as the site of Maritime College, a branch of SUNY.

For more information check out the following podcasts on the above subjects: Trinity Church, Henry Ward Beecher, Great Fire of 1835, Roosevelt Island and Cooper Union.

___________________________________________

PART FOUR: SOPHISTICATED CITY

Courtesy Tenement Museum

34 97 Orchard Street (now Lower East Side Tenement Museum) (Manhattan)

Rarely do we get to see how people of the past lived, in the place they lived it in, with furniture and items they actually used. This tenement from 1863 fell into the proverbial tar pit in 1935 when the building’s owner, rather than renovating and re-renting, simply closed off the upper floors — contents and all — to remain undisturbed until 1988, when urban archaeologists discovered the place and transformed it into today’s Tenement Museum.

Inside lies the story of thousands, of Eastern European immigrants funneling from the Castle Garden immigrant depot to enclaves in the Lower East Side and beyond. As New York in the 1870s and 80s becomes decidedly extraordinary, how amazing is it to find something from the same period celebrating the little banalities of 19th century life.

35 Aschenbroedel Verein building (Manhattan) To make those new Americans feel at home, cultural organizations preserving their foreign music and heritage popped up throughout New York. For Germans, who began coming to the United States en masse after 1850, music was a particular cultural touchstone (as evidenced by early German success story of the Steinways.)

To make those new Americans feel at home, cultural organizations preserving their foreign music and heritage popped up throughout New York. For Germans, who began coming to the United States en masse after 1850, music was a particular cultural touchstone (as evidenced by early German success story of the Steinways.)

To quote a 1896 New York Times article on the German music troupe Aschenbroedel Verein: “A generation ago German-American musicians were not always quite so welcome in musical circles in thsi country as they are now.” In 1873, the organization opened its own clubhouse at 74 E. 4th Street in the East Village — the heart of Kleindeutschland “little Germany” — cultivating a generation of musicians who later dominated the field of orchestral music — favorite of the upper classes.

And the building’s cultural legacy was not over; in 1969, the building reopened as a stage for Ellen Stewart’s La Mama Experimental Theatre Club, without argument New York’s “most influential” off-off Broadway stage.

ALSO: For a more fanciful theatrical transformation, go around the corner to the former Bouwerie Lane Theater, a cast-iron beauty, born a bank in 1873 and transformed into an off-Broadway stage in 1974. It’s a trendy clothing store now.

36 901 Broadway: Lord and Taylor (Manhattan) By the early 1870s, fashionable society had wound its way up Fifth Avenue, expanding between Union and Madison parks with new developments of brownstones, theaters and shops. Heralding this change was the flourishing of Ladies Mile, a collection of tony, often cast-iron-clad department stores.

By the early 1870s, fashionable society had wound its way up Fifth Avenue, expanding between Union and Madison parks with new developments of brownstones, theaters and shops. Heralding this change was the flourishing of Ladies Mile, a collection of tony, often cast-iron-clad department stores.

The trend begun by A.T. Stewart (his first store opened in 1823 north of City Hall) had become a retail revolution. In 1869, Samuel Lord and George Washington Taylor opened a luxury retailer in the heart of the mile, here at 901 Broadway. In my humble opinion, the corner store, in its pompous French Second Empire style, is the most beautiful example of the many storefronts that still exist.

37 Samuel Tilden Home, Gramercy Park (Manhattan)

The flamboyant tastes of the privileged classes made for some outlandish homes. Just contrast the simple tenement above with the ornate 15 Gramercy Park. Structurally from the 1840s, no less than Central Park co-creator Calvert Vaux overhauled the building in 1881 for his client, failed presidential candidate Samuel Tilden. The whimsical exterior decor is literally a reflection of its inhabitant; the writers busts and animals adorning the front were based on a few of Tilden’s favorite things.

The home was considered so lavish that when Tilden died, the prestigious (and private) National Arts Club moved in in 1906 — and has been there ever since.

38 Dakota Apartments (Manhattan)

But not all who could afford such luxury necessarily desired it. By the 1880s, Central Park had changed the city, not only as ‘the lungs of the city’ but the real estate fortunes surrounding. The Upper West Side, still quite remote for most people, was slowly being defined by a new form of domicile — the apartment building.

The Dakota Apartments, designed by Henry Janeway Hardenbergh and opening in 1884, brought lavish lifestyle together with ‘shared services’ and such unique features as a courtyard, community stables and windows arranged for cross breezes — unusual for the time.

ALSO: The Chelsea Hotel began its life as a similar facility as the Dakota; needless to say, it went in a different direction.

Above: the rather farm-looking original Met, today mostly covered up (thankfully!) Courtesy the JSS Gallery

39 Metropolitan Museum of Art (Manhattan)

New York’s primary cultural institution for almost 140 years, the Met reflects everything the city wanted to be in the 1870s — namely, the American Europe. The original building, opened in 1878, would never have thought to cater to the, gasp!, general public or feature, clutch the pearls!, American artists.

How things change. Most notably the entire building, consumed in later additions. However, if you want to see the 1878 original, simply enter by the front, climb that impressive staircase and hang a left — part of the original Gothic, red brick version sits exposed here to this day.

40 Jonathan W Allen Stable (Manhattan) Imagine this: before the early 20th century, the street was filled with horses. Horses, horses, trains and horses. The smell of exhaust, the noise of buses and cars replaced the smell of manure, but a refreshingly quiet clomping. Trolleys would whiz by, trains elevated and spewing black smoke — but horses were still critical to the livelihood of New Yorkers.

Imagine this: before the early 20th century, the street was filled with horses. Horses, horses, trains and horses. The smell of exhaust, the noise of buses and cars replaced the smell of manure, but a refreshingly quiet clomping. Trolleys would whiz by, trains elevated and spewing black smoke — but horses were still critical to the livelihood of New Yorkers.

There are dozens of homes and businesses in New York that are converted stables of days past. In particular, what I like about the stable at 148 East 40th Street, owned by broker Jonathan W Allen who lived close by, is that it was built in 1871 — years before its equine inhabitants would even see (and get spooked by) a future of ‘horseless carriages’. Also, the stable is close to Longacre Square (future Times Square), the center of New York’s horse-driven carriage industry.

41 Domino Sugar Refinery (Brooklyn)

Meanwhile, across the East River, the former village of Brooklyn had expanded to the size of a small metropolis — half a million people, with thriving centers of industry, amassing all the towns in the vicinity to nearly become the size of the present borough today. In 1883, the Brooklyn Bridge united the city with its big sister, and rumblings of a consolidation were underway.

It rivaled Manhattan as the king of monopolies, in particular, in the commodity of sugar. In 1884, the Havemeyer family, who dominated the marketplace, opened their waterfront refinery as the unofficial kings of the city, one of its largest employers. It changed its name in 1900 to Domino Sugar; its distinctive sign (added in 1967) would define the waterfront. Photo Bruce Handy/Pablo 57 Flickr

Photo Bruce Handy/Pablo 57 Flickr

42 Grashorn Building (Brooklyn)

There are many classic buildings still standing from Coney Island’s glory days; Nathan’s Hot Dogs hasn’t budged since it opened in 1916, and the exterior of Childs Restaurant on the beach still looks as good as it did in the 1920s. But the plain Grashorn Building has a special distinction: it saw it all coming.

Unimpressive today, the former Surf Avenue hardware store was built in the late 1880s for Henry Grashorn, a Coney Island business leader who helped foster the city’s reputation as the amusement capital of New York, organizing the neighborhood’s annual Marti Gras parades. Coney Island was a big destination spot in the 1880s, but days of the massive, glorious amusement parks wouldn’t come until the new century.

Today, the Grashorn is dreary, underused and always in fear of being torn down. Kind of like Coney Island always is, generally.

For more information check out the following podcasts on the above subjects: the Dakota Apartments, Coney Island: The Golden Age, Steinway & Sons and a history of Williamsburg

___________________________________________

PART FIVE: IMMIGRANT CITY

43 Ellis Island Immigration Station (Ellis Island)

The most important period in New York City history (the half-century before World War II) began with a major signifier in 1890 — the federal government would now be in charge of immigration, wresting it from the hands of lackidaisical control of the state. By shifting it an uninhabited island in the harbor, new arrivals could essentially be quarantined from the city.

By this time, New York was in the throes of its Beaux-Arts period, and even a processing center for poor immigrants needed to be ornate. The new station (1892) would eventually process 12 million arrivals, most in the following decade and would be first witness to the change from the Irish and German arrivals of the mid-century new hopefuls from Italy and Eastern Europe.

44 Henry Street Settlement (Manhattan) None of these new arrivals is making live in lower Manhattan easier. But charitable New Yorkers and a rising progressive movement proved worthy of the challenge. In 1893, a group of nurses purchased some abandoned Federal Style townhouse — back from the days when wealthy shipbuilders lived close to Corlear’s Hook — and set up a service organization for the sick and educational opportunities for children. In the most densely populated neighborhood in the world, they were the life preserver.

None of these new arrivals is making live in lower Manhattan easier. But charitable New Yorkers and a rising progressive movement proved worthy of the challenge. In 1893, a group of nurses purchased some abandoned Federal Style townhouse — back from the days when wealthy shipbuilders lived close to Corlear’s Hook — and set up a service organization for the sick and educational opportunities for children. In the most densely populated neighborhood in the world, they were the life preserver.

And they didn’t just save people. They also had the unintended result of saving a group of very attractive old townhouses from the crawl of tenements. Today, the landmarked Settlement buildings look like a time capsule from another time.

45 Webster Hall (Manhattan)

The wave of reforms in ethnic communities didn’t stop at basic care. Labor groups organized for better work conditions, better pay and fairer wages. Along the way, they had a little fun too. When Webster Hall opened in 1886, it was as a general service venue. However it soon became an outpost for protest and fund raising for these progressive groups.

Later in the new century, the likes of Emma Goldman would throw lavish money-making parties here, wild escapades that would presage the swinging jazz age. If you’re looking for a temple to pre-1920s bohemia — of the kind that would typify the East Village in later years — you’ve come to the right place.

46 Carnegie Hall (Manhattan)

Oh, but the upper class yearned to have fun too. Operas and chorales! But their entertainments — as much for social networkers as for actual music lovers — were scattered throughout the city, in antiquated old buildings. Enter the vastly wealthy Andrew Carnegie, who cleared away a bunch of old saloons and slums just south of Central Park and opened (in 1891) what is today still the most respected home of the highest cultural arts.

His new deluxe concert hall also set a new mark for the upper crust to cluster. By the turn of the century, the mansions of Fifth Avenue had crawled their way to the southern border of Central Park, just a few blocks from Carnegie Hall.

ALSO: When a luxury apartment building (built in 1890) at Fifth Avenue and 59th Street didn’t quite pan out, they replaced it with The Plaza Hotel (1907).

47 Low Memorial Library (Manhattan) Columbia University, no slouch in the landowning department, moved way uptown during the 1890s to Morningside Heights. And to cap the occasion, they hired the hottest design firm in New York, McKim, Mead and White, to create the campus’s key structures, including the classically inspired Low Library (1895), named after the father of Columbia president (and later mayor of New York) Seth Low.

Columbia University, no slouch in the landowning department, moved way uptown during the 1890s to Morningside Heights. And to cap the occasion, they hired the hottest design firm in New York, McKim, Mead and White, to create the campus’s key structures, including the classically inspired Low Library (1895), named after the father of Columbia president (and later mayor of New York) Seth Low.

The design firm would help define the Gilded Age. Columbia, on top of educating, would be home to decades of new technical innovations. But it wouldn’t be the only place for them….

48 Bell Laboratories Building (Manhattan)

Few today know that the far West Village housed one of the most important homes for media invention in the United States. This collection of laboritories (1898), scattered throughout the city but many concentrated here, were forefront in the invention of the transitor radio, the television set and even laser technology. In the 20th century, the first radio and television broadcasts — and the first sound motion pictures — would come from here. Long after Bell moved to the suburbs in the mid 20th Century, the Westbeth artist complex moved into the building at West and Bethune, reinventing an abandoned industrial space.

49 P.S. 1 (Queens)

A similar repurposing would happen over in Queens. Before 1898, Long Island City was one of Queens county’s most vigorously governors communities, in its later years as an independent city controlled by colorful and corrupt mayor Patty “Battle-Axe†Gleason. The austere First Ward Primary School (later P.S. 1) is evidence of LIC’s maverick days, its first school and the largest in all of Long Island when it was constructed in 1892-3.

Eventually closed and left abandoned, the artists of The Institute for Art and Urban Resources revitalized the structure as a home for art, and today it’s affiliated with the Museum of Modern Art under its original numerical designation as the P.S.1 Contemporary Art Center.

50 Brooklyn Borough Hall (Brooklyn)

The worst demotion in the history of New York City buildings — at least since the federal government left Federal Hall — happened here, on January 1, 1898, when the lovely Brooklyn City Hall became Brooklyn Borough Hall. The consolidation of the five boroughs would unite the heavily urban with the deeply rural, big city politics with small town political machines — all in an attempt to meld the competing priorities of a metroplitan area into one defined urban vision.

This meant the powers of the great city and town halls of all the other cities and towns were greatly diminisheed. In Queens, the town hall of Jamaica is long gone, as are those village halls in Staten Island. Luckily, the city of Brooklyn had become coterminous with the county of Kings by the time of consolidation, so its grand city hall, completed in 1849, just modified its responsibilities. Today, its one of Brooklyn’s proudest buildings, a reflection of a time of independence.

For more information, check out our podcasts on Ellis Island, Carnegie Hall, Webster Hall and Columbia University

View History of New York in 100 Buildings in a larger map

5 replies on “A History of New York City … in 100 Buildings (Nos. 1-50)”

My God, when do you find time to work? First the tremendously informative podcasts and now this! I hope there is a book in the works. If not, there should be. You guys rock!prowc

What about Morgan Library?

http://nyc.listofcity.com/ The Big List of New York City

What a great compilation. I agree with the book idea above. I love this city and I can’t never get enough info about these beautiful places. I am looking for info on tours of these buildings, especially the ones outside of Manhattan.

This is a wonderful compilation.. Absolutely worthy and should definitely be in Book form!